A month or so back, I did a post on Karlynn Holland, a Brooklyn-based artist who can see, and draw, your inner demon. She is one of those artists that is able to create her visions in many different media – be it illustration, sculpture or collage. She can bring you back to life from your dry, dusty bones as a trained forensic reconstructor. Holland also works with and among some influential bands and people in underground metal. And today I am happy to bring you a fascinating interview with Holland, who will take us on a journey through her life and inspirations.

Hey Karlynn, how are things in your world?

Awesome.

How did your Demon Portraits series come into being?

The first demon portraits were quick drawings I could do in a couple hours. They were a series of six floating heads, each with a stoic and contemplative expression, eyes closed and looking inward, each head surrounded by an eight sided geometric web and the pure potential of an otherwise blank page.

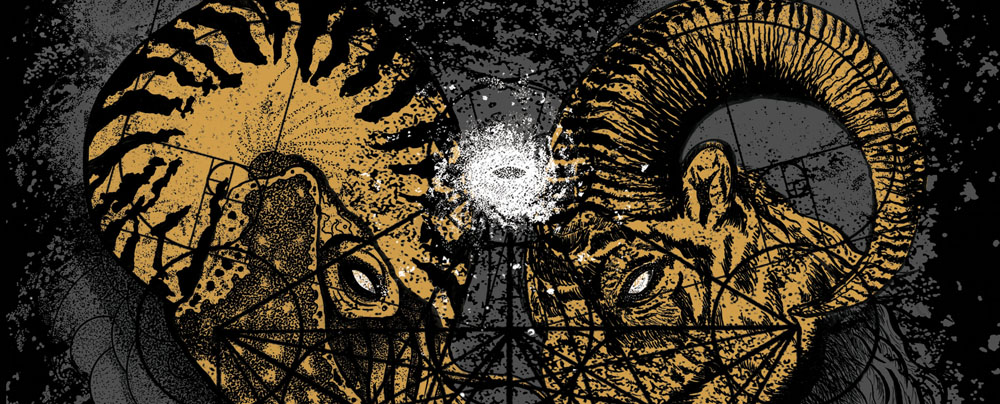

The idea was to create a kind of anti-icon. I was raised Catholic and much of the early artwork I was exposed to was religious, ranging from statues in the church we went to on Sunday morning to Michelangelo. In college, I returned to much of this work as stylistic inspiration. I noticed demons hardly ever resembled humans but rather their impish cousins with tails, wings, and claws. Demons were something other than human, yet they were also symbolic of a negative potential, something we could become. I wanted to neutralize this potential and create an image wherein the demon was more or less human and familiar. I wanted to close the distance between the angelic, human self and the demonized other. The result was these praying demons.

Lev Weinstein was the first demon portrait. Before him, I made up the faces and worked from imagination. Lev and Nick McMaster had a band in Chicago called Astomatous, and after seeing the first set of praying demons, they requested demon portraits in lieu of band photos for the album The Beauty of Reason. So, Lev was also the second demon portrait and Nick McMaster was the third. It was Nick’s request that they have growths rather than sharp horns protruding from their heads. After college in Chicago, I moved to New York City. I wanted to do another demon portrait and asked some of my friends if they would be interested in having their demon portrait drawn. Everyone I asked said yes, starting with Brandon Stosuy. I realized there was great potential in asking my subjects what they wanted as their demon quality. Brandon chose dead trees. Mick Barr chose to be a Walrus. Vanessa America chose to be a unicorn. Seldon Hunt wanted to see double. In all cases, what was chosen was not something I would have picked or even imagined, but the choices are what make the portraits really revealing. The head is an exterior likeness of the person’s face, any reasonably talented draftsman can do that. It is in the process of demonization that the interior person comes out and that is what gives these portraits power and a real sense of the person they represent.

The demon portraits are a series of portraits of my friends and peers that are meant to be a subversive questioning of our traditional notions about who is demonized and what the social connotations of being demonized are. Demonization implies poor behavior and a lack in one’s quality of character, but I make it an honor to have one’s demon self realized. No one is more honored than me. These people are not only my closest friends, they are also people I truly admire. All of them have made things, written things, played things that continue to inform and enrich my life and lives of many others. The practice of making these portraits, which I intend to continue, is my way of collecting and remembering the gifted and talented people in this world I have had the great fortune of knowing.

In your Black Forests and Gosling Moss series, what landscape are you envisioning?

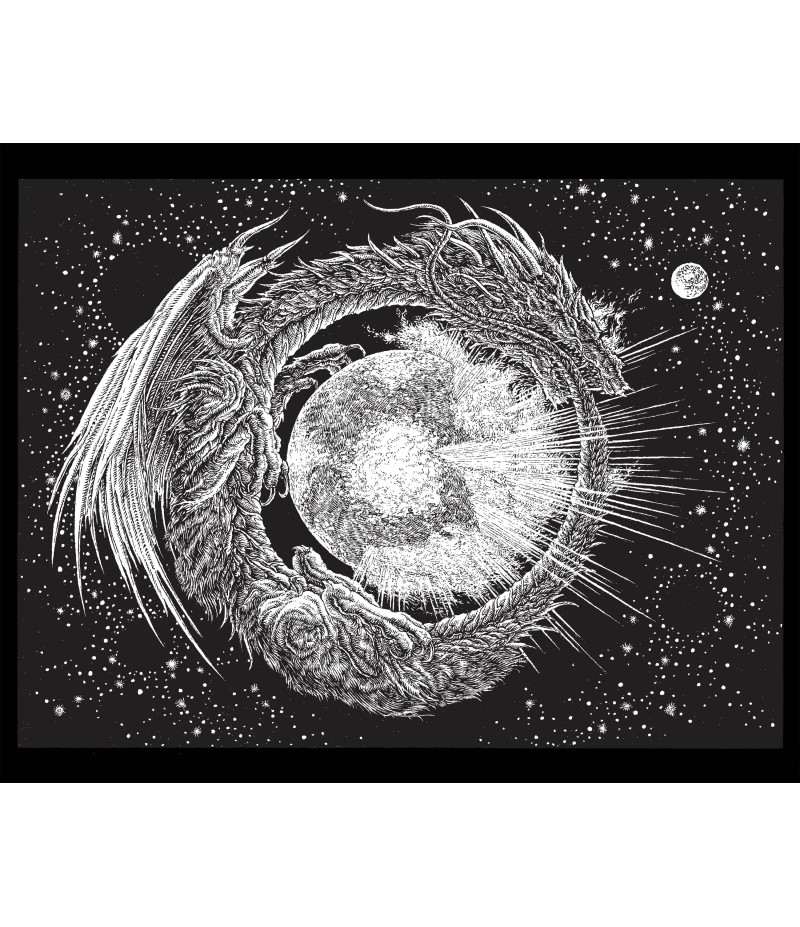

The Forests came first, so I’ll start there. These were a combination of two visual sources. The first is the sound wave image that Peter Saville created for Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures cover. The second was hair follicles of the inner ear. I wanted to create an auditory forest, minimal, desolate, post-apocalyptic even. The trees were meant to also be representative of the thing in us that first responds to audible vibrations in the air. I was listening to a lot of black metal at the time, Drudkh, Krallice, Horna, and Inquisition, which helps explain the choice of forest as the overarching visual metaphor.

As for the Goslings Moss, I was music trading with James Plotkin. I told him to check out WOLD and described their sound as snow ripping the flesh off your face. He seemed to think that was pretty accurate. At the time, I was listening to a lot of drone doom, Black Boned Angel, Boris’ The Thing Which Solomon Overlooked and, of course, Earth 2 Special Low Frequency Edition were in heavy rotation. Jim gave me a copy of a Goslings/Warmth album, Heaven of Animals. It is superb and his description of it was perfect: like wrapping your ears in a cozy blanket of blackened moss. I thought the image of that texture, this amorphous blob of black moss wrapped across a page, was simply irresistible. So I started drawing and as I make progress, I scan the drawing and post it to the internet, mostly to remind myself to keep working on it.

Was art a big part of your childhood?

I have drawn since I can remember. I had a talent for math, but it was ultimately art class that always held my interest and early on it became something I explored. My parents were very encouraging, I think mostly because they thought it would balance out my studious academic nature. They bought me supplies and took me to museums. In high school, they let me travel to pre-college programs. Little did they or I know it would become the passion of my adult life. No one in my family is an artist, or even a professional musician for that matter. My mom is an accountant, my dad’s an engineer. They are both ex-military. Visual art, and music too, were things I largely found and explored for myself.

Who inspired you to become an artist when you were younger?

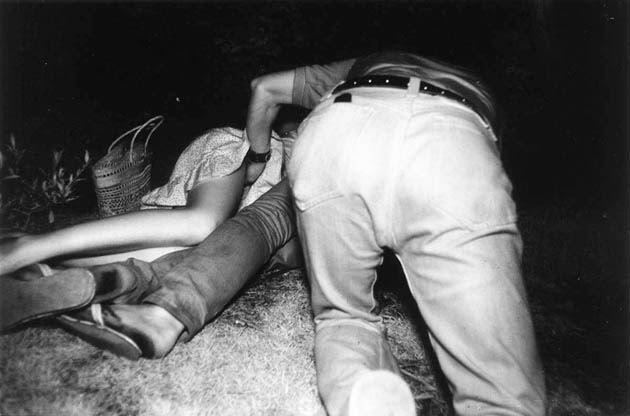

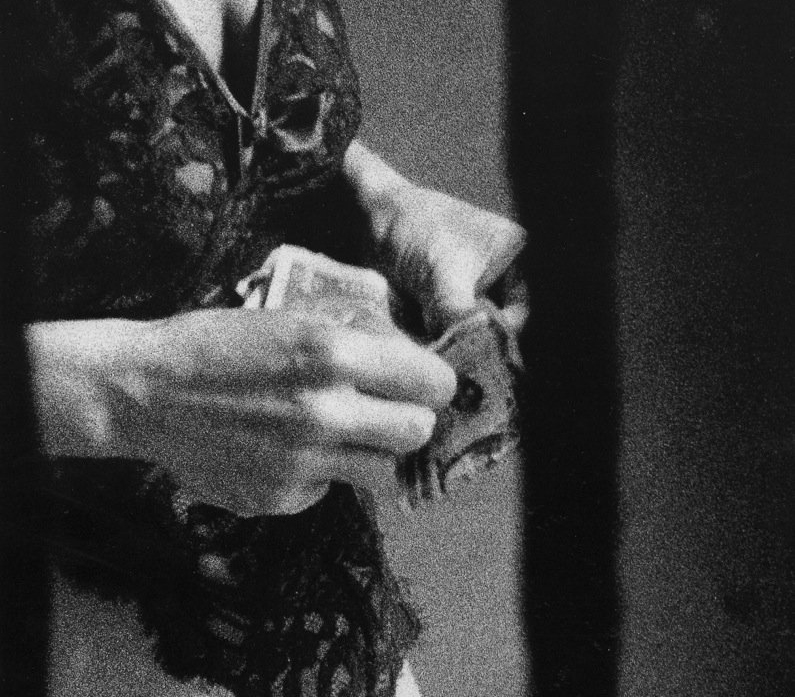

I’m not sure who the first artist was that I encountered that made me think, “I’m going to do that with my life”, maybe it was Will Eisner, or M.C. Escher. I taught myself to draw by copying my dad’s vintage comic books, in particular, I really liked the work of Eisner in the noir comic series The Spirit. Other artists that made serious impressions on me were Gerhard Richter, Lee Bontecou, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Otto Dix and Sally Mann. Mann’s exhibition “What Remains” as well as Sugimoto’s “Theaters” and “Seas” are delicate photographic monuments to temporal mortality that still leave me a short of breath. Discovery of the masters of anatomical illustration were also pretty key, in particular Jan van Calcar who illustrated Vesalius’ seminal anatomy text.

Where did your life begin?

I was born in Germany on an army base just outside of Frankfurt. My birth certificate lists my birthplace as West Germany, the Berlin wall was up when I was born. My father was a paratrooper and in his regiment was a woman by the name of Karlynn O’Shannesy. Karlynn O was a lifer, one hell of an officer, and recently retired from the reserves as a general. I’m honored to be named after her. As a side note, the spelling for Karlynn is a German variation, a feminine for Karl, and although I was born in Germany and have a German name, I don’t have any German ancestry. My mother did used to tease me growing up that I was adopted from Gypsies. The story goes that my parents said they’d look after me, but I was so bad that they tried to give me back. However the Gypsies said no way and then told them that if they, my parents, ever tried to give me back again or give me away to other parents, they would put a hex on them. I don’t actually look much like my parents (I’m taller than both of them) so who knows, maybe it’s true. I lived in Germany until I was about two, then we moved a couple times between army bases in New Jersey and Maryland before my dad retired and we settled in rural southern Maryland. I hated growing up there and vowed when I left to never go back. Then, Maryland Death Fest started up, and now I can’t wait to go back every year. Life is funny like that.

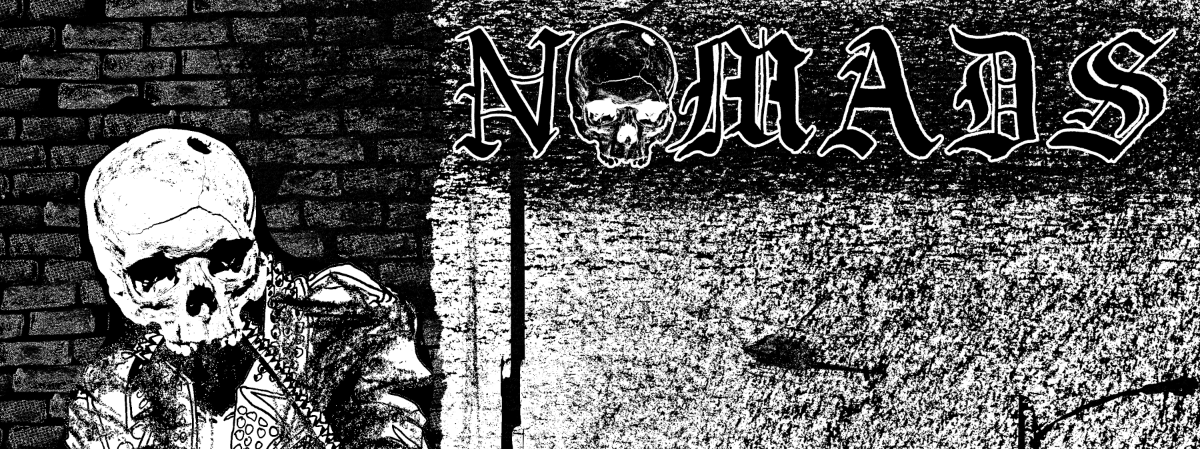

Your band logos have a very distinct style, like they are natural formations of living things. How do you find this aesthetic in a band’s music?

My goal is for my logos to contain within them everything contained in the music they signify. As any true head banger knows, one can look at pretty much any heavy metal logo and know, generally, what the band sounds like. Punk, thrash, grindcore, death metal and black metal have evolved over time and each has a style, as well as a stylized logo, that is distinctive. The logo looks like how the band sounds.

For the most part, when I make a logo I start with the music of the band, listening for bands that are similar. I ask the band what inspired them. This research culminates in a list of bands, and sometimes also includes movies, television shows, and other cultural remnants. I look at the logos on the influence list and study them. Next, I feel out the overall shape I am trying to create, bending, twisting and placing letters until they balance just so. Once the letters are placed, I think of the word as the skeleton of the logo, I flesh out their style, adding the style of the music the logo will ultimately represent. In this way, the logos really are natural formations of a living thing, the band.

When did forensic reconstruction become an interest of yours and when did you decide to pursue it as part of your career? What is the most fascinating forensic reconstruction you have done?

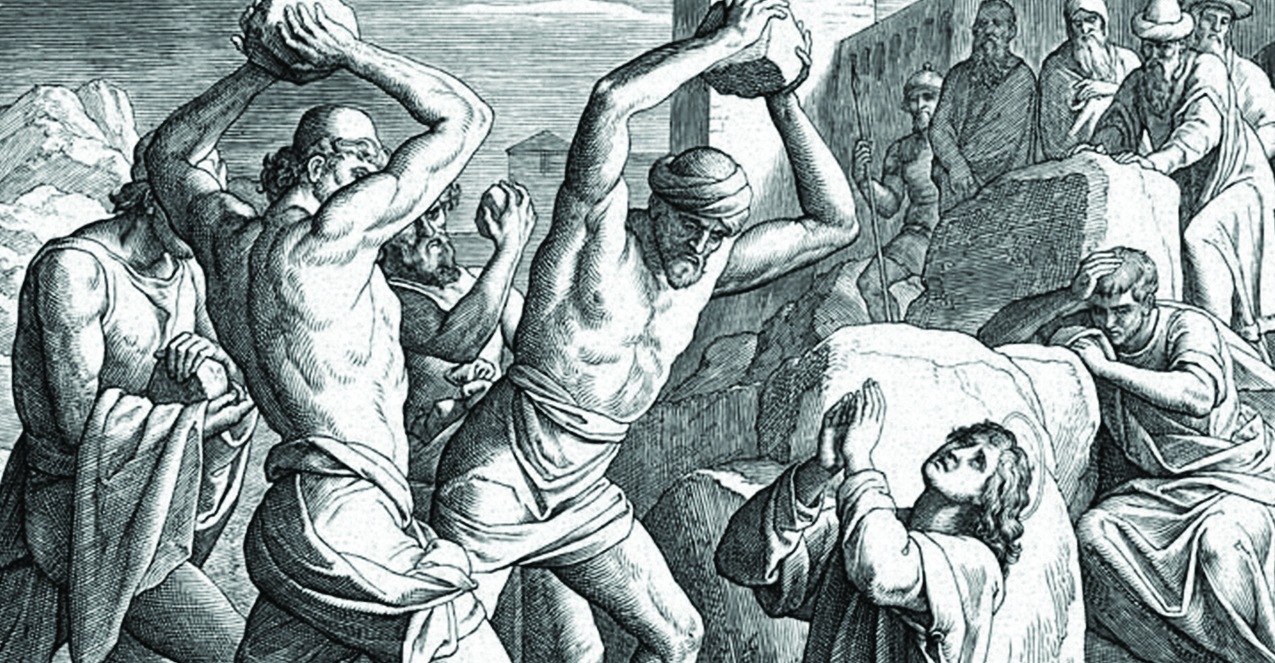

Bones are the natural archives of our mortality. They survive the flesh and inscribed on them are our scars and the strength of our muscles, our diet and in some cases our diseases. I am endlessly fascinated by them, for they are as unique as each one of us and are shaped by everything we do and all that we consume. And they just look so freaking cool.

Forensic reconstruction first became an interest of mine in college after I took a Bioarcheology class. It was the only course offered to undergraduates that allowed us to work with human remains. I have always been fascinated by anatomy and anatomical illustration, so I felt that studying the human body was an essential part of my artistic and personal education. It was not an easy course. The exams were composed of bone fragments that each student had to identify, sex and accurately age, but I took to it. Halfway through, I started helping the TA with homework and study guides and eventually made an online guide to the human skeletal system that the class still uses today. After moving to New York, I learned that the New York Academy of Art offers a forensic reconstruction class. You work from a plastic copy of a skull and using the Manchester method of facial reconstruction, you build the musculature out of clay and wrap a layer of clay skin over that. The result is a rather accurate likeness of the individual, which in most cases is close enough that someone who knew the person in life would recognize. Confirmation of the individual’s identity is made from dental records or DNA. This method can be simulated by computers as well, especially since the invention of 3-D scanners, but you really have to be able to be capable of doing it the old fashioned way if you want to have any success using newer technology.

The vast majority of forensics work is done by law enforcement, and beyond that, a few civilians with government positions. I was taught reconstruction by Joe Mullins, who works for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. I continually offer my talents and training, but it’s really much more a hobby than a career. The last forensics work I did was in college. Someone mailed my professor a box of bones one day that they had found in a cardboard box in their basement. The police weren’t able to offer much help and since my professor was a forensic archeologist, they thought she might be able to shed some light on the matter. We put the skeleton together and looked it over. The bones were rather old and several had serial numbers written on them, indicating the bones were most likely from a collection somewhere where they had been archived and sure enough, the residence had at one time belonged to someone working at a local museum. They had probably just brought their work home with them one night and forgotten to take it back. The remains themselves were quite interesting. The skeleton belonged to a child no older than 9 or 10 and there were clear burn marks covering the bones, as well as carving marks where flesh had been cut from the limbs. It was our best guess that this individual had been the subject of a ritual or cannibalistic sacrifice. Normally we might not have jumped to such a sensational conclusion, but the remains had been collected and cataloged. It was probably for a reason. Pretty neat thing to find in your basement!

What part has music played in your life and in your artistic career?

Music is a central part of my life and today is the primary force behind my creative output. What I have tried to do is to create visual representations for what I hear. That representation has taken on many forms: portraits, logos, and landscapes. I am more curious than anyone about what form it will take next.

You practice so many different art forms – drawing, painting, sculpture, collage – is there one medium you feel most at home with, or do they all express different aspects of your creative spirit?

When something begins, I don’t totally know what it’s going to take to bring it to its fullest potential. How could I? I haven’t made it yet. In the making, I use what I have at the time to best realize my vision. That said, almost everything I do starts as a drawing and much of what comes after feels more like an extension of the drawing than a separate practice.

Thanks for a rad interview Karlynn…you took us to a lot of fascinating places! We are looking forward to your future projects…

Explore Karlynn Holland’s portfolio HERE.

lux

March 25, 2012 at 4:18 pm

Rad.

jabuhrer

July 6, 2011 at 12:47 pm

Thanks for the interview. Love Karylynn’s work.