PostApoc, by Liz Worth.

PostApoc, by Liz Worth.

Now or Never Publishing, 184 pages.

The underlying anxiety of disaster fiction always stems from the question, how would we survive if the engine of industrialized civilization were to irreparably break down? Toronto-based author Liz Worth’s debut novel PostApoc has at its core the nihilistic observation that, if there really were nothing left, then there would no longer be any reason to survive. As such, it’s appropriate that the story begins with an ending – albeit a complicated one – in which protagonist Ang undertakes a suicide pact with her inner circle of friends, then finds herself the sole survivor. In a world that increasingly resembles painter Hieronymus Bosch’s surreal vision of hell in The Garden of Earthly Delights, Ang finds that escapism is a healthy means of coping with the slow, nightmarish collapse of not only the world but of reality itself.

In the 1995 introduction to his novel Crash, J.G. Ballard observed that, thanks to our dependence on and consumption of media and technology, fiction has become the reality of modern life: what we experience is, for the most part, artificially constructed. PostApoc‘s otherwordliness reads like a subtle, esoteric form of magic realism that invokes reality as a byproduct of spells, divinations and hallucinations. Its characters divide their time between the hard scavenging for scarce resources and the pursuit of equally rare highs from generator-powered concerts or greyline, a psychedelic drug rumoured to be mixed with the ashes of the dead. By now we’re all well-acquainted with disaster scenarios, and author Worth knows this: Ang and her friends aren’t melodramatic about survival – no one is out to play hero, to lead the others to safety, or to provide false comfort (at least, not without the promise of some tangible, material reward). Their only goals are, alternately, subsistence and escape from the tedium of a slow-motion apocalypse. What sets PostApoc apart from other recent apocalyptic tales is its Ballardian ennui – early in Ballard’s Crash the protagonist says, “After being bombarded endlessly by road-safety propaganda it was almost a relief to find myself in an actual accident.” One has the impression that, despite the impossibility of their survival, PostApoc‘s characters seem to have come to terms with fate rather easily, perhaps for similar reasons – at one point, Ang reads in a modified survival guide, “It must have been a mistake because I am just waiting.”

It’s an interesting reflection of contemporary life: we remain preoccupied with our various distractions and carry on with the same well-worn routines despite the telling signs of global climate change and the threat to our natural resources (particularly water purity – Ang relates early on that the end truly began when the lake supplying her city’s water suddenly dried up.) Popular disaster stories, such as Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead, maintain an angry stoicism in the face of adversity which seemingly suggest that, even if society falls apart, our humanity and morality would remain. PostApoc has no such illusions but it is not brutal, either – whatever the fate of individual characters, death is accepted, without judgement, as a natural, inevitable, and often merciful part of life.

INTERVIEW:

PostApoc is about the aftermath, or various particular aftermaths; what got you thinking/writing on this theme?

There was a time when I was obsessed with the end of the world. I believed it had already started and at any moment we’d turn a particular corner and everything would crumble.

I think there were some personal uncertainties that were driving me to this. I was underslept and paranoid and unsure about where my life was headed at the time.

But there were also external factors that were affecting me then. I was reading a lot about global warming, air and water pollution, the oil industry, and the impact of consumer culture on the physical and emotional environment. I’d recently finished college for two years of my school career I’d worked part-time in retail. Both summers had a lot of smog days; people with respiratory problems were being told to stay inside. People were asked to take their kids to the parks early in the morning if possible, due to air quality. They asked people to leave their cars at home if they could.

But still, there was a steady stream of vehicles in and out of the parking lot at work. The air conditioning was blasting constantly and people just shopped, shopped, shopped. I thought, ‘wow, is this worth it? Is this where we’re putting our time and energy when there are certain people who can’t even go outside today? We’re all going to get dragged down in this.’

But then I was working there, and I was just as much a part of the problem, so I also had a lot of conflicting feelings towards myself.

The humidity down at the shore of Lake Ontario made everything stink – the water smelled like sewage and it was always a filthy green brown. That also made me think of the end of the world: where would we go if everything broke down and stopped working tomorrow? How would we access clean water from a fresh source?

Even though all of these things were on my mind a number of years before I started writing PostApoc, they definitely influenced my line of thinking for this book. It was almost as though they’d retreated underground inside for a while and resurfaced as a novel.

The novel begins with two precipitating events, the suicide pact and the strange phenomena beginning to occur in the world – does Ang see a link between them? Does her survivor’s guilt make her think, if only unconciously, that the ritual deaths facilitated the ending of the world?

Yeah, there is definitely a link between the two for Ang. I wanted her to question her role in it all, to wonder if she was somehow responsible for the end of the world because she didn’t die when she was supposed to and so set the universe off course. I wanted that to haunt her and make her as paranoid as the events she had to struggle through once the end came.

What does Greyline mean to Ang and her friends? How did it find its way into the story?

I wanted PostApoc to have a hallucinogenic quality, and I wanted the characters to still have access to drugs and alcohol, but I also didn’t want to make the drugs conventional. In the book the world has changed, but Ang and her friends still want a lot of the same things. It’s not like they don’t want to get high or drunk, and really, if everything was going to shit I think a lot of people would hope they could at least get wasted in the process, or find a way to escape, at least temporarily.

So I worked in grayline as a different kind of drug, “made from the shake of magic mushrooms and the ashes of the dead,” as Ang tells it. For her and her friends, it starts out as just another way to get high – they’ll take what they can get at that point – but it soon becomes a bigger problem, because it really messes with their heads and gives a nasty comedown, the kind that leaves you wanting more.

In the world of PostApoc, the end of the world is dogged, first and foremost, by hunger and hygiene issues. How does this comment on our culture’s obsession with cleanliness?

I don’t think our culture is all that obsessed with cleanliness. There are a lot of measurements in place to encourage people to practice proper hygiene, but a significant amount of people still don’t participate, even in basic hand washing. Even this year, a study from Michigan State University found that only five per cent of people wash their hands long enough to actually kill germs. That particular study also found that 10 per cent of people weren’t washing their hands at all, but depending on where you get your information you can find higher stats than that.

I think the people who are really obsessed with cleanliness, coupled with the amount of marketing we see for cleaning products, makes it seem like we are a bunch of germaphobes, but I don’t think that’s the case for the average person.

A few months ago I saw someone change their kid’s shit-filled diaper in the booth of a restaurant. There was a pile of puke on the stairs at the subway station by my house that went untouched for two weeks. It just kept getting stepped on and stepped on and stepped on.

These are just a couple of examples, but I see things like this all the time and I think no, we have a lot of options available to us to clean up with and we have more knowledge about how viruses, bacteria, and diseases are spread, but it doesn’t always connect with the general public.

There is also still a lot of magical thinking out there when it comes to these things. People still believe that temperatures make you sick, not germs. And I think there’s a lot of apathy around it, too. A lot of people don’t care about getting sick when they feel healthy. They only care when they feel unwell, and then it goes away, and they forget about it.

To tie this all back to the book, I had read a study about the impact of antibiotics on our drinking water – because anything that is us eventually returns to the earth, and because we share water supplies with so many people, those things come to us, too.

I had read a study – I can’t remember who did it now – that had predicted that the constant flush of antibiotics in our water supply could create drug-resistant superbugs that could eventually evolve to travel through our drinking water. It was a theory, but it really freaked me out, because you can’t control what people are putting into their bodies and how it affects the water you rely on. I thought about that for a long time, and when I was writing PostApoc I thought about what would happen if that was reality, and if people were still unclear, or apathetic, about how contamination spreads.

Your vision of the end is populated by young people still trying to get high; do altered states lend themselves to this kind of surreal experience?

Definitely. Some early reviews of the book have mentioned that the readers weren’t sure at time what Ang was hallucinating, dreaming, or actually living through – or if the world was even really ending. Some were unsure whether Ang just wasn’t high the whole time.

And I like that, because I wanted those questions to be there. I wanted to confuse the reader and let them wonder.

Was there anything you were listening to, watching, or reading for inspiration during the writing of PostApoc?

I don’t listen to a lot of music when I’m writing because I find it too distracting. When I listen to music, I like to pay attention to it, and I am very lyrics-focused and it’s hard to write when you’re listening to someone sing.

But I found Cocteau Twins’ Treasure to be one album I could write to during PostApoc, so that became my main background sound.

I can’t recall having seen the word “goth” mentioned anywhere in the novel – was that a deliberate omission?

Goth has played a big role in my life – I even thanked Rozz Williams (the late Christian Death frontman for those who need to know) in the acknowledgments as an influence – but so have other subcultures.

Because my first book was an oral history of punk in Toronto, I’m often tied in with punk and people assume that punk is my life, but if you were in my brain, or my apartment, you’d find that I have a lot of different sources of inspiration. I find it too limiting to be just one thing, or to be part of just one thing. I can’t cut myself off like that, and I can’t follow rules well enough, either. Things feel very fragmented, and sometimes too regimented for me.

The bands and music scenes created in PostApoc are an amalgamation of everything I’ve liked and experienced, combined with things I’ve wished to find in the world but haven’t yet. I didn’t want to label genres because I wanted these scenes to be whatever the reader wanted them to be. Whether they cross genres or not is up to interpretation.

PostApoc‘s setting is Toronto, the so-called “center of the universe”; could this apocalypse have happened anywhere else?

It does happen in Toronto, but I never name the city in the book, so that people who don’t know Toronto and have never been here can make the city their own, but those who do recognize certain street names and areas will get the references.

I mentioned some other cities, but as things are breaking down and communication and media are becoming unreliable or unavailable, a lot of things become rumours. People are isolated to the areas they’re in for the most part, because they’re not always sure of where to go.

I do think what happens in this story in Toronto could happen anywhere, but any city’s demise would still have traits specific to it. An apocalypse in the Nevada desert would be a lot different than in a small town in the Yukon, because resources and climate and environmental impact would vary.

Is there anything you find particularly apocalyptic about Toronto?

As it would be in any big city, I think if the end of the world was here we would be really limited as to what we could live on. Food supplies would run out – only so many days’ worth of food is supplied within a city, anyway – and then what? Our rivers are polluted, our lake is polluted – what would we do?

And if people had gardens or a way to feed themselves, how would they protect their property?

If you were set up somewhere secluded and had survival skills and knew how to live off the land, you could be fine. But in a city you’d be competing with a lot of people just to get by.

Have you ever been on the subway in Toronto in rushhour? If you want to see a dog-eat-dog scenario, that’s an adventure for you. That alone brings out the worst in people.

I’m really not sounding optimistic, am I?

What sets Canadian disaster stories (e.g. Atwood; Tony Burgess’ Pontypool Changes Everything, etc.) apart from American apocalypses?

That’s a good question. I think with Margaret Atwood, she is so universal that she could be writing her novels from anywhere. I don’t think there is anything particularly Canadian about Oryx and Crake but it is particularly Atwood.

But I think sometimes in Canada we tend to think that our writers are spending too much time focusing on Canadian settings or experiences. But it’s not as if American writers aren’t doing the same – a lot of authors set scenes in cities they know, or take inspiration from them no matter where they are living. I think geography can always be a major influence on someone’s writing, but I don’t know that it always sets things so far apart as we think.

No matter where I was living, I’d still be paranoid as all hell, so I probably would have still written PostApoc but my landmarks might have been different, you know?

What did it mean for you, writing this book?

At first I didn’t even have any intention of writing this novel. I’d been working on a totally different book but I kept getting ideas for this one and one day I realized this was the book that I needed to be working on instead.

I had no idea where it would go when I started. It was very spontaneous. Some people spend years just thinking of the book they want to write, but this one seemed to come out of nowhere.

But as I became more committed to it, I started to find it was digging deeper and deeper into my own personal experiences. Even though it’s a piece of fiction with its own intentions, for me personally this book ended up meaning something a lot more personal than I had planned.

It deals with suicide a lot because thoughts of suicide were something I’d struggled with for a long, long time when I was younger. As I got into my mid-20s I started working through a lot of those feelings, and writing about them in articles and blogs, but I never thought I would write about them like this. By the end of PostApoc I felt like I’d let it all go, and I don’t think I will be able to write about suicide like this again. It really was a cathartic experience, even though that’s not what I was seeking at first.

Magic (e.g. sigils, omens) is often mentioned throughout the book; what role does it play in your apocalypse?

Magick, omens, dreams, spirit animals – they all play an important role in my life in general, and it’s been finding its way into a lot of my work lately.

I wanted to make sure it was included in PostApoc in some way, and I figured if all the rules of the world are changing, then magic could certainly be a part of those changes.

Shelley and Anadin are often at the centre of the magick that happens in this book. Ang is the only one who interacts with them and they have very strange, witchy ways. They try to help Ang, try to guide her, but they give her a survival guide that’s been perverted with spells and folklore and fortunes. Not even their magick can save what’s been undone.

How did your personal experiences as a young adult inform the story?

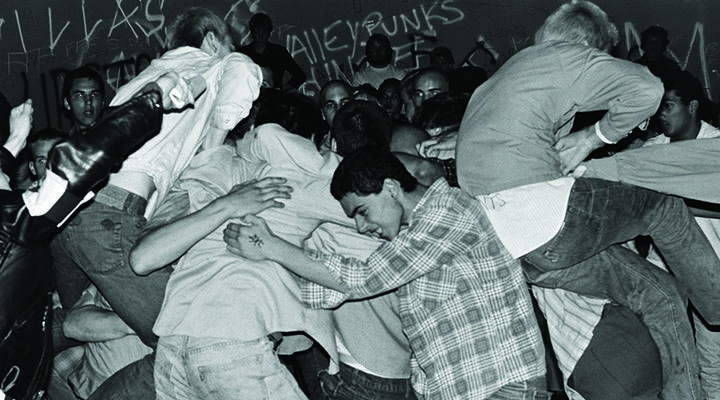

I was a teenager in the ‘90s and there were some really interesting things happening in pop culture then. Everyone was talking about heroin. Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain were doing it. Calvin Klein had his “heroin chic” look all over billboards. Bands like Alice in Chains were huge, and they had major drug problems, too.

It seemed like a lot of people died, or almost died. And when you’re young and everyone you look up to, and everything that is being sold to you, seems to relate back to death or drugs, that can have an interesting effect on you And I wanted to work that into the story of PostApoc, to talk about bands that are pushing things so far they have to die because there is nowhere else to go. And I thought, of course bands could inspire people to kill themselves. Doomsday cults have done it – why not good looking musicians?

I know now that I took things way too literally back when I was growing up, but at the same I’ve talked to people since then who picked up on the same feelings, so maybe there was a collective consciousness there. I also look at the people who are famous now and I wonder if maybe it was as dangerous as it seemed.

Because that’s what I thought it was: dangerous. And I liked that feeling. It shaped me into believing that art should be scary. That it should always be on the edge of something. It should bring discomfort, but also inspire, and that’s what I felt when I was younger: creative despite my unease.

I still feel that way. The times have changed but inside it’s the same.

Is it too late for our civilization to change its course?

If you’d asked me this five years ago I would have said no, but even though I’m coming across as a totally paranoid downer in this interview I’m actually a lot more positive about the future than I used to be.

I’ve gotten really interested in astrology since then and the astrologers I follow are always talking about how we are living through awakenings, how certain discussions and issues and even disasters that we are facing are helping to bring people to a new way of thinking and living. I like to think along those terms a lot more than walking around believing that everything is about to fall apart.

You still have to be a conscious person, though, even as a positive person. You can’t deny that there are problems, but you can have hope.

New Comments