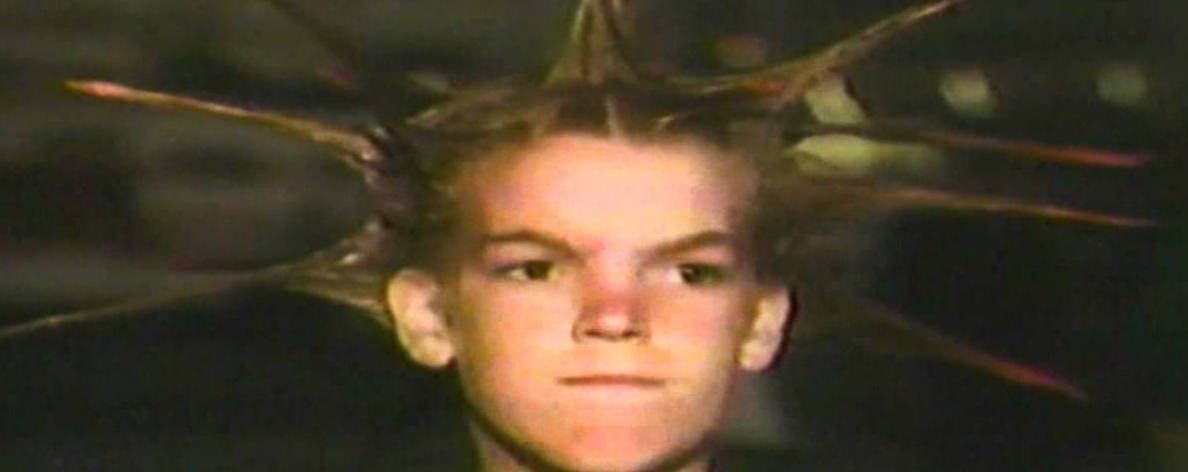

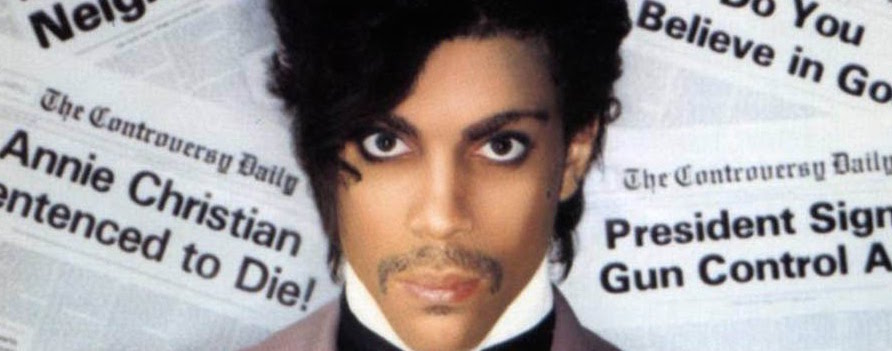

Immaculately dressed in a white shirt, black waistcoat and trousers, his gaunt face sharply framed by his slicked-back blonde hair, David Bowie became, in the mid-70s, the Thin White Duke. The Duke emerged out of the Young Americans era, but first announced himself on the title track ‘Station to Station’, a ten minute opener which sees the Duke wait patiently before finally, after 3 minutes 18 seconds, he croons ‘The return of the Thin White Duke, throwing darts in lovers’ eyes.’

The stories that surround the making of this record are folkloric. Rumours of an exorcism that happened in Bowie’s L.A. home are almost given credence by the evocations of occultism in the Duke’s lyrics. More chillingly was the Duke’s flirtation with Nazism and his alarmingly fascistic messianism espoused in interviews. But perhaps most infamously was Bowie’s addiction during this time; Station to Station was recorded in such a cocaine haze that it left him snow blind, so much so in fact that Bowie doesn’t even remember making the record.

Arguably, the Duke was Bowie at his maddest. Drug-crazed with malevolent poise, it was certainly Bowie at his most transgressive. In retrospect, he has even gone so far as to call the Duke an ogre. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that Bowie only remembers this time fragmentally with an almost critical revulsion. It’s a fitting way to distance oneself from such troublingly authoritarian ideas. But the Duke’s real subversions were in fact overshadowed by his crazed politics. His cartoonish antagonisms only served to cloud what were the real strengths of the Duke and his music, which weren’t his politics or anything conspicuous but a sonic obscurity, difficultness and unpredictability that proved formative for his later work. The title track itself is a ten minute exploration that moves from samples, feedback and art-rock jamming to pop melodies and a lounge-esque vocal swagger. In the wake of the Berlin Trilogy, the first two installments of which came a year after Station to Station, the Duke was and is often dismissed, despite his own insistence in the title track ‘it’s not the side-effects of the cocaine,’ as a drug-fueled blunder. But it was the Duke who, before the Berlin era, told us that ‘the European cannon is here.’

It has been seven years since Oxbow released The Narcotic Story, and ever since its announcement we have been waiting for the arrival of the follow up record called The Thin Black Duke. We know that it is being recorded at 25th Street Recording in Oakland and is being produced by the legendary Joe Chiccarelli. And followers of Oxbow’s Facebook would have seen some of the unassuming photos that were posted along with two very short video snippets taken from the sessions; in one of these we hear feedback raging from the guitar of Niko Wenner. But unlike the stories surrounding the Thin White Duke, talk of the Black Duke has been slightly more muted; nothing of an exorcism in an L.A. home and no crazed drug stories.

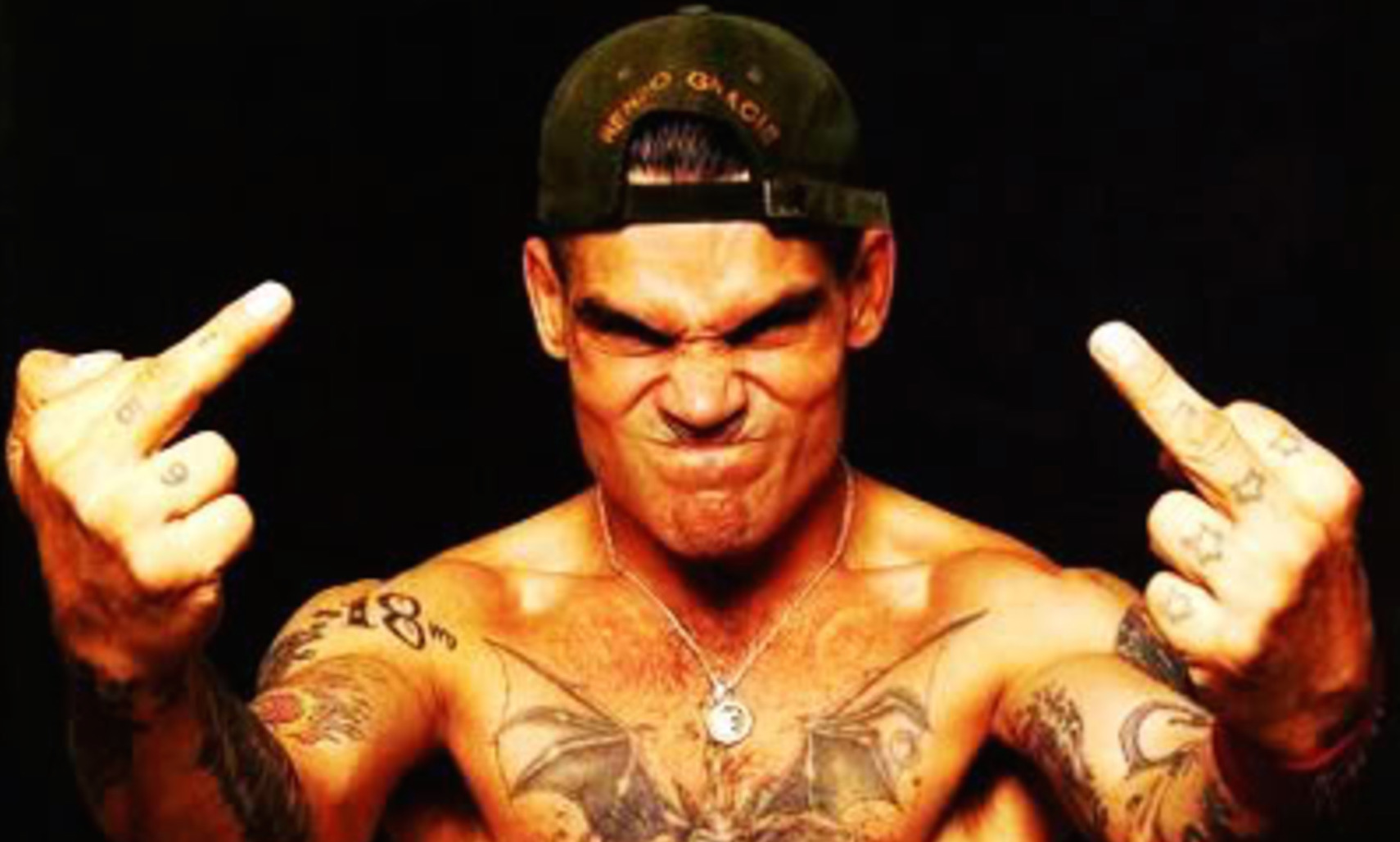

But it is not difficult to see why Oxbow have chosen to play with the persona of the Thin White Duke in their title. Oxbow have always circled an obscure malevolence and carried themselves with an avant-misanthropy reminiscent of the Duke but without, of course, his fascistic politics. Oxbow’s music is political to the extent that every gesture in the world could be construed as political but their politics is certainly not obvious or a central aspect of what they do. Instead, everything in Oxbow’s music exists in a subterranean world of obscurity and desperateness that is seemingly never ending; their music is like a starvation on the brink of death that is never relieved. Stories of the The Thin Black Duke have been no exception with talk of an advancing desperateness that, as frontman Eugene S Robinson tells us, ‘reeks and ‘stinks of death.’

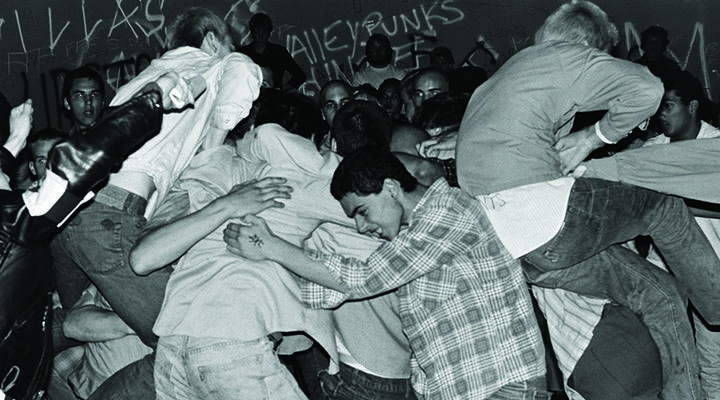

Death is a recurrent motif in Oxbow’s music. Their 1989 debut record Fuckfest was, as Robinson tells us, recorded as a suicide note. By ’91s King of the Jews this suicide became homicide, where the abyssal nature of death was turned outward in what was their first step towards their trademark crushing misanthropy. But like their politics, Oxbow’s misanthropy and their relationship to death is never cheap or obvious. Robinson’s chaotic vocal delivery that ranges from screams and shouts, bassy spoken word, whispers, to slurred and almost drunken fragments mask his stories. What is gleaned from his vocal is both fascinating and disturbing but is made all the more so by the fragmentary way in which they are delivered. What is audible and clear is equalled by what is mumbled and hidden, creating layer upon layer of feverish intrigue. Oxbow’s world is an infernal world of violence and sex but it’s told to us in nightmarish scraps, stories half remembered and half muddled, but delivered with an unsettling resolve and aggression.

Like the arrival of Bowie’s Duke persona, Oxbow always put us on the back foot. By the mid-90s with Let Me Be a Woman and particularly with Serenade in Red their music gains in complexity. During this time Oxbow, like the Duke’s Station to Station, start to cover more ground; they play with more textures, cover more space with things getting increasingly angular, obscure and disturbing. Track ‘3 O’clock’ from Serenade in Red is cinematic with its lazy and echoed drum beat, Robinson’s unnerving vocal spasms and fits, and Wenner’s sporadic guitar that fills and empties the track in equal measure. It’s a tired and exhausted piece of music but is arguably, like the Duke was for Bowie, Oxbow at their maddest and most desperate.

But Oxbow don’t stop here, instead their madness continues to deepen and the despair which seems to call out from their music only worsens. Their 2002 record An Evil Heat picks up from ‘3 O’clock’ with a muted guitar and rhythm section which, unpredictably building to pulverising crescendos and interruptions, frame Robinson’s vocal. But added heavily to the mix, on tracks like ‘Stallkicker’, is a kind of broken-blues, a blues tangled up in their infernal madness. This record is a sickness, a punishingly dark piece of music that never brings relief even in the quieter moments. The final track, ‘Shimmer’, 32 minutes in length, sustains the unease of the record in a trance inducing loop of guitar feedback and riff, with rolling bass and drums.

As the Thin White Duke, Bowie looked, quite literally, to be at death’s door. In interviews from this time we see a drug-ravaged face, gaunt and malnourished from his diet of red peppers, milk and cocaine. Oxbow’s relationship to death, however, is less literal. It is not about an end-point but rather the feeling of suspended animation. The recurrent despair and pain in Oxbow’s music creates a sense of unending disquiet. There is no relief from the intensity and seriousness Oxbow circle, not even a relief brought by death. Instead, as listeners we are more like characters in a Beckett novel, waiting for a relief that never comes.

Their last record, The Narcotic Story (2007), is their finest incarnation of waiting. It is Oxbow at their most composed, their most experienced and their most disturbed. The rawness of early Oxbow is held in close proximity to a madness that has paradoxically gained in refinement and composure. It’s a record of unrelenting brilliance that never tires and from which we can never escape. Even in its final moments, on the last track ‘It’s the Giving, Not the Taking’, we are left waiting for relief and momentarily we think we have it, with the comforting sound of birds and a light breeze passing through us. But these sounds slowly fade and with them fades the momentary relief they bring.

And it is at this point that we were left waiting for The Thin Black Duke. As with every new Oxbow record, we can’t be sure what the Duke will bring. Perhaps like Bowie’s transformation into the White Duke, it will be Oxbow’s maddest creation yet. If their discography is anything to go by, their intensity and sense of adventure has only gained, which would suggest that The Thin Black Duke might just be the scariest ogre of all. It will no doubt carry a swagger and malevolence equal to that of the White Duke, but most likely with an even deeper obscurity and difficultness. Oxbow are not an approachable band and their music is not easy but for those of us who have been left waiting in the silence at the end of The Narcotic Story, we cannot but wait for the horrors that the The Thin Black Duke could bring.

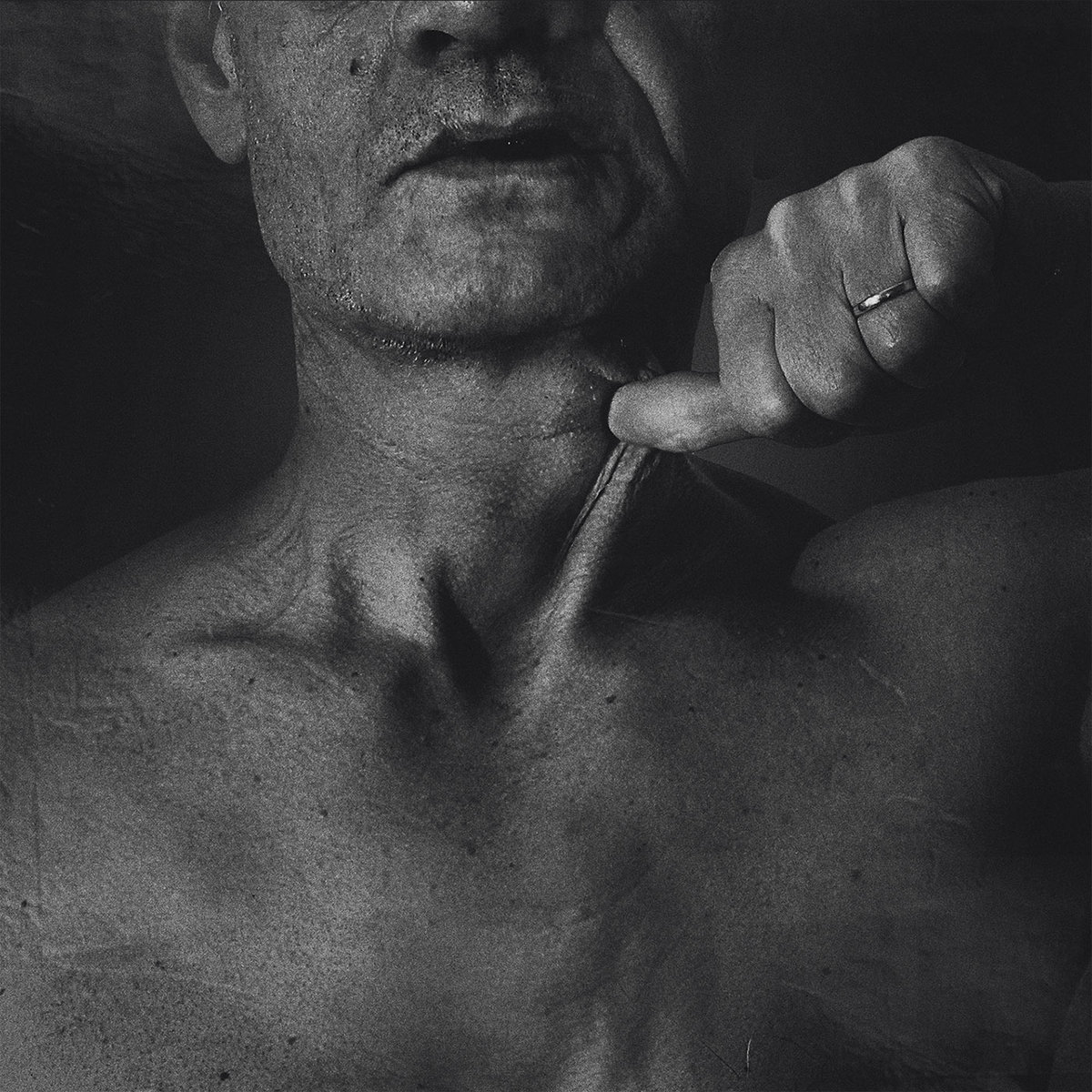

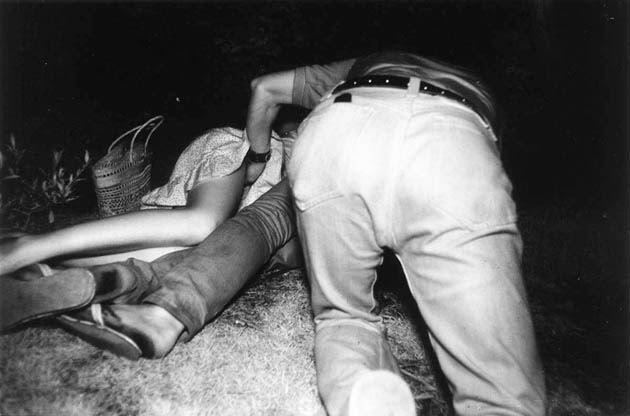

Banner photo by ©by Frank Schmitt via www.stacholero.com

Heinz Renfield

September 24, 2014 at 12:10 pm

Helo ? still, that b/w photo is not made by cat rose. ©by Frank Schmitt via http://www.stacholero.com

CVLT Nation

September 24, 2014 at 12:40 pm

Sorry! I’ll change that now!

Heinz Renfield

August 4, 2014 at 12:22 am

Hi, the black & white photo used here was done by me.

©by Frank Schmitt via http://www.stacholero.com

Ally Hewitt

July 1, 2014 at 12:31 pm

Really, really well written and fascinating. Just had to go dig out An Evil Heat

Adam

July 9, 2014 at 1:37 pm

Thanks a lot Ally. Glad you liked it!