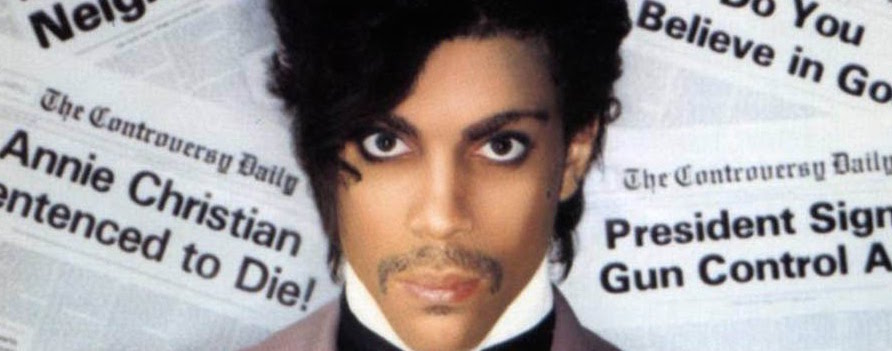

Music. Arson. Suicide. Murder. Art. Black metal. Until The Light Takes Us is the first feature length documentary chronicling the history, ideology and aesthetic of the infamous Norwegian musical subculture.

This interview with American filmmakers Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell is from the vault, before the international release of the DVD last year.

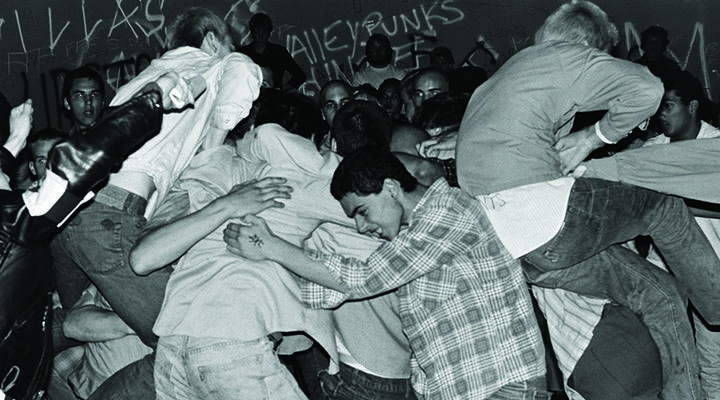

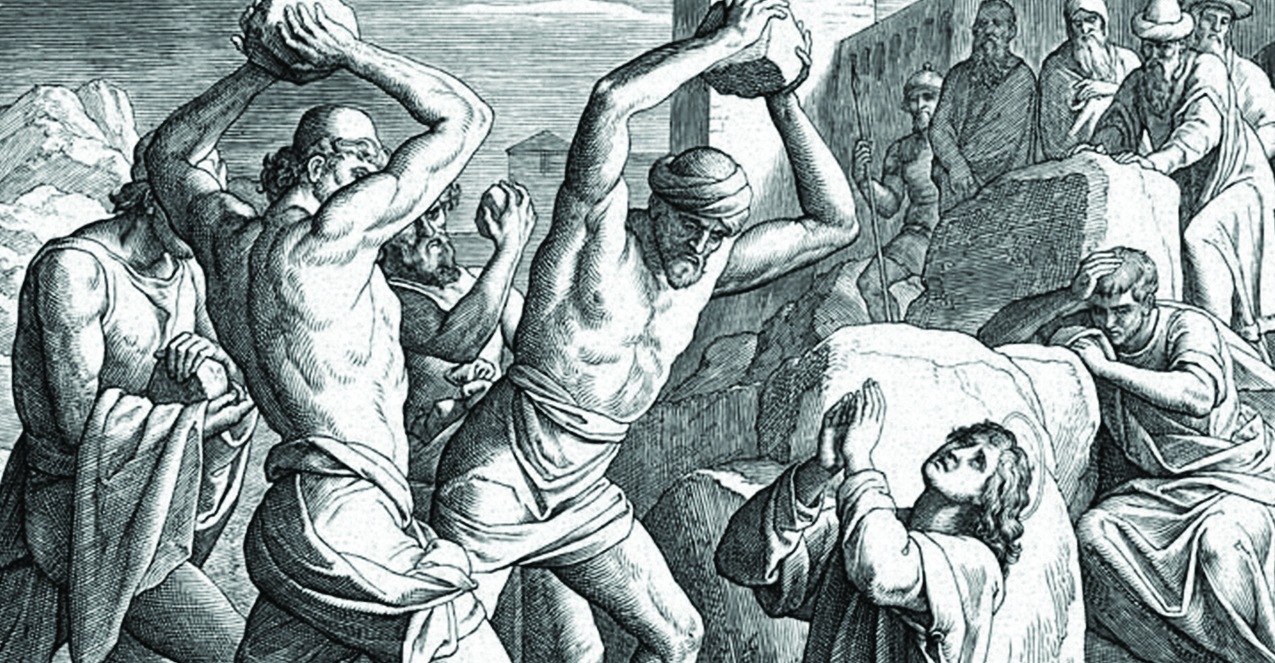

The tale behind early ‘90s Nordic black metal is rife with misconceptions. Immortalised by a sequence of sordid events, ranging from church burnings to the murder of musical kin, the history attached to the subculture has achieved a level of notoriety far beyond its initial obscure intentions.

But true Norwegian black metal – as it has come to be called – was never about this chain of impropriety; it was about the music. Black metal has emerged as an art form, grounded in anti-establishment principles. These days even appreciated by the low-fi and roots communities for its original purity and relevance, it is a story has been left to fester – and one that has always deserved to be told better.

Even more enigmatic is it took two filmmakers from a noise-esque, experimental background to make the document that may ultimately become a defining artifact in articulating the legitimacy of the genre. And in the case of Brooklyn-based pair Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell, the co-directors of Until The Light Takes Us, this nonlinear approach created the distance needed to break down the barriers black metal prescribes itself to.

The first to state they were by no means aficionados of black metal, Aites and Ewell’s interest towards the project piqued simply because no one had been able to adequately document the genre’s roots cinematically before.

“It all started because we were trying to find a film about black metal,” Aites explains. “And there simply was not one. We kind of were turned to start listening to black metal through a friend who runs Amoeba Records (San Francisco), because he knew we’d like the low-fi roots of the genre. We are kind of like locusts; once we find something we like, we try to devour it. Because we got into black metal later on, there was this whole library of music to go through. It intrigued us that there was this whole scene of great music, yet there was no film about it. We were actually starting on a different film, but when we realized there was no definitive piece on black metal – we just had to do it.”

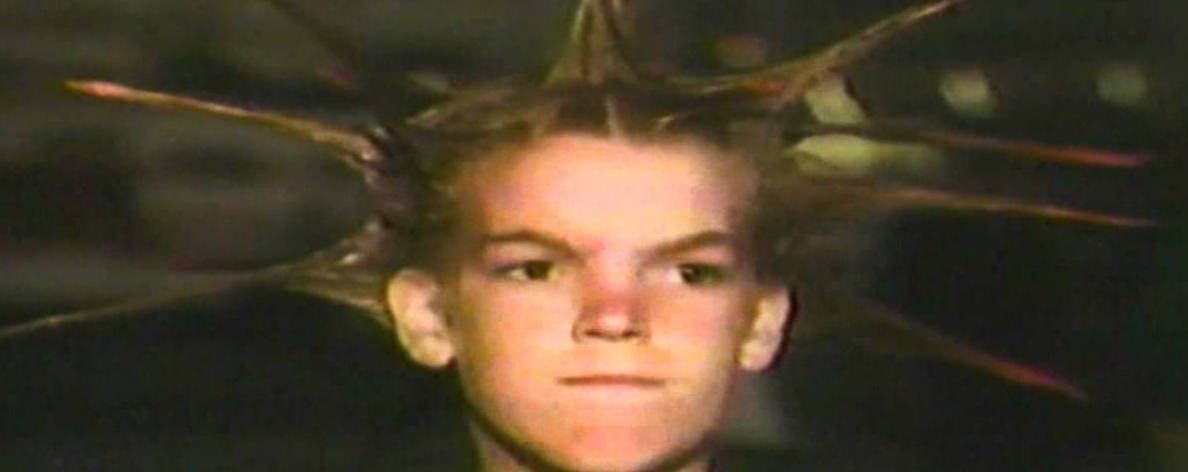

The film itself follows the lives of three men who developed the genre. Deceased guitarist Oystein ‘Euronymous’ Aarseth, one time leader of Mayhem and Helvete owner – a local record shop that specialized in metal music and was ground zero for the movement – Burzum’s Varg ‘Count Grishnackh’ Vikernes – recently paroled from prison after serving 16 years for the murder of Aarseth and arson – and Darkthrone mastermind Gylve ‘Fenriz’ Nagell – who is still focused on the music ‘til this day.

Until The Light Takes Us also draws heavily on the shotgun suicide of original Mayhem frontman Per Yngve Ohlin; aka ‘Dead’. For those unfamiliar, the tale goes that Dead’s body was found by two of his bandmates, the then still living Aarseth and drummer Jan Axel ‘Hellhammer’ Blomberg, who took pictures of his mutilated corpse (one which became the cover of the 1995 bootleg live album Dawn Of The Black Hearts) and allegedly kept fragments from his skull, which Hellhammer rumoured later to make into a commemorative necklace.

Researching the movement on home soil for 12-months before relocating to Norway for two-years during filming, the duo went about interviewing all of the genre’s major players – even surfacing those who had blatantly refused to appear on screen, or in print, before. Though this was not an easy process, according to Ewell. “We realized how difficult it was going to be when, after five months of writing back and forth to Varg, he was still saying no,” she says.

“Making a black metal documentary without Varg Vikernes is like making a Rolling Stones documentary without Mick Jagger. It took eight-months to get him on-board, which was a harrowing thing because we weren’t going to make the film unless we had both Gylve and Varg – it just wouldn’t make sense. So when Varg finally agreed to meet with us, it was sort of a pressured environment to convince him – as we’d already put a lot of money into the film and had been working for some time.

“But I think what really appealed to both Varg and Gylve was that this wasn’t going to be a film with narration. It is about the musicians themselves, telling their own story. We even turned down financing from a number of people, who wanted us to do one of those films that would have us heavily involved in the meeting process. Like a “…now we are going to see Varg” type of thing; that’s not what we wanted.

“What really resonated for me was the obvious bond between Varg and Gylve. They are completely estranged, but they would never say one bad thing about each other. They still cared about what the other was saying about the other. But you just couldn’t ignore the fact that Gylve created a scene that was based on anti-commercialism and one of his best friend’s turning it into everything it wasn’t meant to be. There’s an inherit conflict there.”

New Comments