Requiem

On August 15, 2009, 14-year-old Kevin Barrera was shot, killed, and left beside train tracks in Richmond, California. Nearly four years later, the gruesome scene featuring a cruiser and police officers standing near the dead body was discovered, archived on Google Maps. After discovering the image, Barrera’s distraught father contacted Google, imploring them to remove them—which the company did little more than a week later but not without hesitancy or surprise. Brian McClendon, vice president of Google Maps wrote in an official statement, “Google has never accelerated the replacement of updated satellite imagery from our maps before, but given the circumstances we wanted to make an exception in this case.”[1] Meanwhile, the case remains cold, with the coordinates of 37.951592,-122.360448 now showing only dirt in an ignored corner of Earth.

cebook Google Maps Death Scene featuring Barrera and police of Richmond, CA

Updated Screen Shot 2016-01-27 at 8.12.57 PM by the author.

Born-Digital, Die-Digital

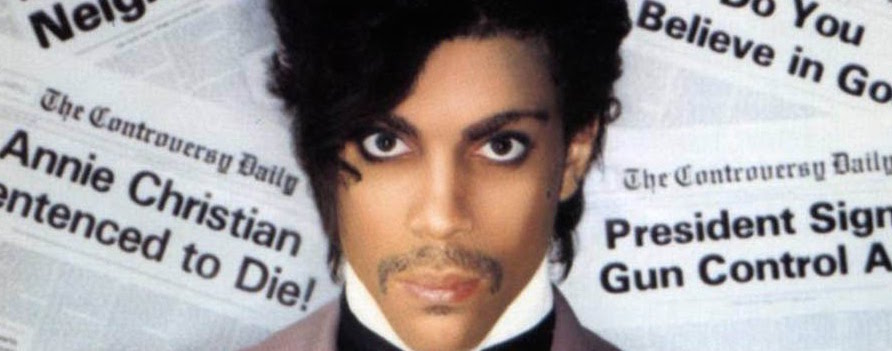

White Metal Candle Flame.GIF via You Mattered

In 2008, John Palfrey and Urs Gasser, expanding on the work of Marc Prensky’s “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants,”[2] popularized the term “born digital” to refer to a generation of Westerners born after 1980 who “live much of their lives online, without distinguishing between the online and the offline. Instead of thinking of their digital identity and their real-space identity as separate things, they just have an identity (with representations in two, or three, or more different spaces),” and who “feel as comfortable in online spaces as they do in offline ones. They don’t think of their hybrid lives as anything remarkable. Digital Natives haven’t known anything but a life connected to one another, and to the world of bits, in this manner.”[3] Rather than only referring to “objects” whose origins are the digital: website, blogs, GIFS, born-digital also means human materials: artifacts, profiles, text trails, search histories, our lived lives—with “digital,” problematically, a synonym for anything “Internet-related.” Palfrey, Gasser, and Prensky’s perspective is mostly one that champions the born-digital by considering their interests and methods—facilitated by technology—to be unstoppable progress.

By 2016, born-digital has moved beyond those born in the 1980s and early-1990s, those who transitioned into the Web 2.0 of the post-2000 bust, and instead, now we must also consider the possibility that the birth of a new user begins digitally. As soon as parents-to-be post their announcement (more increasingly in a performative way via YouTube or other services), featuring a sonogram photo of the fetus, a new-user is born-digital—perhaps never just analog. Parents will continue their trek via life-blogging the pregnancy, their preparation, and additional sonograms. Eventually, the child is born and there awaits an account and a profile for the new-user. Its digital baby footprint passively created by its parents—it will never know a choice. The new-user is born unto the digital and there too will it one day die, leaving behind a legacy that there never used to be: “one-week old,” “two-weeks old,” death, and the beyond (e.g. memorials).

Writing in the early 2000s, Prensky, concerned with education, describes two kinds of content—categories resulting from a “digital singularity,”[4]—they are Legacy and Future. Beginning with the Future, in other words the content of the Internet: software, apps, social networks as well as more transhumanist subject matter: “robotics, nanotechnology, genomics.”[5] Legacy content (e.g. “reading, writing, arithmetic, logical thinking, understanding writings and ideas of the past”)[6] implies outdated systems, practices, and traditions, which, we are told are of lesser importance to the born-digital. Legacy content is not necessarily to be discarded, though, instead, Prensky argues for teaching Legacy content “in the language of the Digital Natives.”

In 1997, 18% of American households reported having Internet access at home. This number increased to 41.5% in 2001, and by 2013, 74.4% reported Internet use.[7] From 2005 to 2015, the percentage of all Internet-using adults who use social networks rose 66%.[8] With the increase of users in these social-spaces, especially those digital-immigrants (Prensky, 2001), comes an increase of those “dying-digital.” “As Facebook adds more users and its current user base greys, 580,000 US based Facebook users will pass away in 2012 and 2.89m will die worldwide,” wrote Nathan Lustig, co-founder of Entrustet (now Secure Safe) an online service that managed “digital assets.”[9] The Digital Beyond updated these numbers estimates 972,000 U.S. Facebook users will die in 2016.[10] One must understand that Google Maps death-scenes are destined to become a ubiquitous phenomenon—along with social network cemeteries. Over time, we may know more dead than we know living among our friends list.

Unsurprisingly, discussions of the digital afterlife, while increasing, have been taken on primarily by legal scholars and data companies—monetization of identity being their main concern. Too few wonder about philosophical, psychological, social, and political ramifications of digital death. Although initially caught off-guard with the images of Barrera, Google has created Inactive Account Manager (aka Google Death)[11] for the posthumous handling of accounts, and Facebook now has a “friendly” help section titled “What will happen to my account if I pass away,”[12] which offers memorialization, legacy contacts, and permanent deletion options.

Proving one’s death to Facebook. Screen Shot 2016-01-28 at 2.02.38 PM by the author.

Borrowing Prensky’s Legacy and combining it with the legacy referred to by legal scholars, we might understand a new digital Legacy, one that considers death itself as outdated—“Death is Wrong,” reads the title of transhumanist activist Gennady Stolyarov II’s children’s book (2013).[13] The quantified self, self-surveilled, shared and archived among various platforms is further processed down to the bits and pieces of our genetic makeup. The analog-user dies; the digital-user lives forever. The idea that the parts make up the whole is nothing new, or as Ray Kurzweil theorizes, the data might resurrect the user (i.e. avatar), but perhaps the born-digital user never dies or never was flesh. If a child’s entire life began and ended with a Facebook account, then, problematically, who owns their life? Who owns their bodies and their autobiography, and who might resurrect the dead?

Cover illustration of Death is Wrong via Amazon.com

Timothy Leary, who saw the Internet and Web 1.0 as proto-transhumanist vehicles for immortality, championed “designer death.” Leary planned to webcast his suicide over the Internet. Any sense of empowerment, today, may simply be further commodization of the self from life to afterlife—perpetual users whose accounts are still used to share and promote content by corporations or the likes of MyDeathSpace.com. In the spirit of Leary, only services like the Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, or the now defunct, Seppukoo, might give real ownership over one’s digital afterlife by offering users the opportunity to commit digital suicide: passwords and photos are changed (made unavailable to the user), accounts are taken off public searches, friends, notifications, are all removed and as much of the digital trail as possible is extinguished. Resurrection is made impossible.

Below is a select list of death-spaces, a starter-kit for dying-digital. The standards, aesthetics, and problems range considerably as entrepreneurs seek mainly the business of death—much different than the suicide option:

Screen Shot 2016-01-31 at 12.45.40 PM by the author.

- YouMattered.com: Retro design and content, YouMattered (est. 2014) allows users to customize a memorial for the deceased. Users have the option to pay their respects by choosing to: light a candle, place a flower, offer a prayer, upload a picture, and share a story. Candles are animated gifs, and there are various styles to choose from. In this example, featuring the developer’s mother, adult contemporary music plays along (a reminder of an earlier Web 1.0, when midi reigned supreme) while flower petals softly fall across the screen. Each memorial is social web friendly, capable of feeding content back and forth, and making it easy to share the dead. Also interesting is the inclusion of a “Related Memorial” option where effectively the dead may network.

Candle options via You Mattered. Screen Shot 2016-01-29 at 4.02.11 PM by the author.

- DeadSocial.org: Various sites, like Dead Social (est. 2012), allow users to create an account and author social media messages or e-mail that will be sent out posthumously by the service. Stay in touch with your loved ones forever—or however long you paid for a subscription service in the case of many of these services. Dead Social is launching version 2 on February 1st, 2016, and plans to provide 10,000 new accounts with their version 3.

- DeathSwitch.com: But, what happens when “media” dies? There once was a thriving Yahoo! Chat community, but it is now overrun by bots, and once there was Friendster, then MySpace, and now Facebook. We must consider the life and death of media if they are to be the executors of our legacy. There is a sense of naive foreverness that accompanies the user’s confidence in the digital network. In the case of Death Switch (est. 2006), one of the older digital afterlife services providing posthumous emails, the company folded. They write: “Users who purchased a premium membership after October 22nd, 2014 will receive a refund for their current year’s subscription. Users will receive one last round of ‘reminder’ messages. Users who do not respond to these messages will have their switches triggered at the scheduled time before their service ends. You will be able to access your ‘My Messages’ page to retrieve your messages and attachments until December 1st, 2015.” Clearly, it is possible that the services, too, may not live to tell your story.

- TheDigitalBeyond.com: A blog discussing the issue of digital life and death. For more examples, visit their Online Services List.

*Illustration by the author, 2016.

[1] http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/18/tech/web/google-maps-dead-body/

[2] http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

[3] http://www.borndigitalbook.com/excerpt-2.php

[4] “This so-called “singularity” is the arrival and rapid dissemination of digital technology in the last decades of the 20th century.”

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

[7] http://www.census.gov/hhes/computer/

[8] http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/

[9] http://www.nathanlustig.com/tag/facebook-death-rate/

[10] http://www.thedigitalbeyond.com/2016/01/972000-u-s-facebook-users-will-die-in-2016/

[11] https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/3036546?hl=en

[12] https://www.facebook.com/help/103897939701143

[13] http://motherboard.vice.com/read/a-transhumanist-wants-to-teach-kids-that-death-is-wrong

New Comments