Via. The Appendix

Written by Chris A. Smith

The chant began less than two minutes into the first song. An undercurrent at first, just a few hecklers. But it got louder with repetition, each wave building on the last. Soon the chant threatened to drown out the band itself.

“Fuck you! Fuck you! Fuck you!”

It was tough to take. But it was entirely in keeping with everything else about this disastrous tour. The angry crowd in Long Beach. The broken-down van in the Sonoran desert. Sixteen tickets sold in Portland. Now, onstage in San Francisco, the members of Discharge—the fastest, meanest, most uncompromising English hardcore punk band of the 1980s—must have wished they were somewhere, anywhere else.

It was quite a comedown. On the band’s previous North American tour, in 1983, Discharge had played sold-out shows to thousands. Up-and-coming thrash metal bands Metallica and Slayer, both of whom would be headlining arenas soon, cited the group as a prime influence. Iconic punk fanzines like Flipside, which could make or break reputations, pronounced them “fucking great.”

But it was 1986, and a new era was dawning in underground music. Punk’s energy was waning, and metal was on the rise. Many punk bands were moving toward a more metallic sound, melding their radical politics and D.I.Y. approach with metal’s musical chops and low-end heft. For some bands the transition went off without a hitch. For others, though, it was akin to choosing sides in a civil war. Discharge, one of the most influential bands in punk history, chose wrong.

Back in San Francisco, the band skidded to a halt twelve minutes into the set. The singer, Cal, attempted a bit of bravado to counter the booing: “I love it when you talk dirty!”

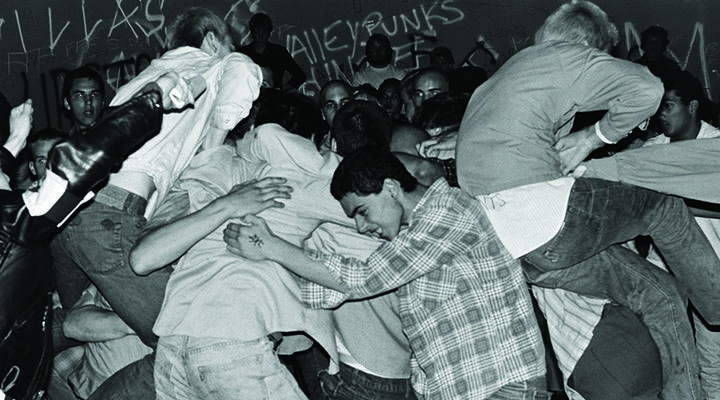

Nobody in the audience was fooled. Out beyond the stage, the crowd was a roiling sea of leather-jacketed anger, a mosaic of jeering faces and raised middle fingers. San Francisco, like every other city in America, hated Discharge.

At first, Discharge didn’t stand out from the legions of punk bands that sprang up in the wake of the Sex Pistols’ incendiary 1977 debut. Indeed, the group’s first demos are filled with Pistols-esque songs of non-specific rebellion. The recordings sound like the work of bored teenagers, which is exactly what they were. The band members, working-class kids from the provincial town of Stoke-on-Trent, had a good idea of what their futures held—a succession of crappy jobs or a life on the dole, punctuated, perhaps, by nuclear annihilation. Punk offered an outlet.

The first wave of punk burnt out quickly. By 1980 Sid Vicious was gone and the Clash was branching out into reggae. Punk, the media declared, was dead. The guys in Discharge felt betrayed by their heroes, as this 1980 interview with the fanzine Grinding Halt demonstrates:

G.H.: What do you think of all the original punk groups now then?

Cal: There’s none left now, they’ve all either sold out or split up, there’s only a few bands left now who’re any good.

Rainy: They were good then, but now they’re shit…

Abandoning its Pistols-worship, Discharge began forging its own path. In the process, as Ian Glasper recounts in his history of English punk, Burning Britain, the band helped kick off punk’s second wave.

Musically, punk’s first wave hadn’t been all that far removed from regular rock’n’roll. “God Save the Queen,” with its hummable melody and simplistic chord changes, is clearly a relation, albeit distant, of Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones. The difference is in the attitude, in Johnny Rotten’s adenoidal snarl.

Discharge’s revamped version of punk bore little resemblance to anything that had come before. It was faster, harsher, and often almost entirely lacking in melody. The riffs were generally three-chord affairs, but they were played at warp speed, accompanied by a rumbling bass and a merciless, galloping drumbeat. The songs rarely topped the two-minute mark. As Garry Maloney, who drummed on some of the band’s best recordings, explained to a ‘zine called Trakmarx, “We just embraced speed—the concept—not the drug—took it to its logical limit.”

The vocals, meanwhile, weren’t anything like Johnny Rotten’s. Cal’s hoarse barking just sounded angry. His lyrics, anarchist jeremiads against government oppression and nuclear war, were like nihilist haikus, delivered without metaphor, nuance, or humor. Here’s the entirety of “Is This To Be,” from the band’s seminal 1981 EP, Why:

Scorched earth is all that’s left

Where trees and flowers once grew

A trail of destruction

Death and destructionNothing left but wasteland

Littered with human flesh and bone

A trail of destruction

Death and destruction

Soon, as Glasper notes, Discharge was topping the UK’s independent charts and making waves across the globe. Even reviewers who hated the music couldn’t help but admire the band’s uncompromising attack. “I certainly never wish to listen to this record again when I’ve completed this review,” a critic wrote in Sounds magazine. “And yet Discharge are the very best of their kind. Their energy, as we used to say in ’77, is amazing.”

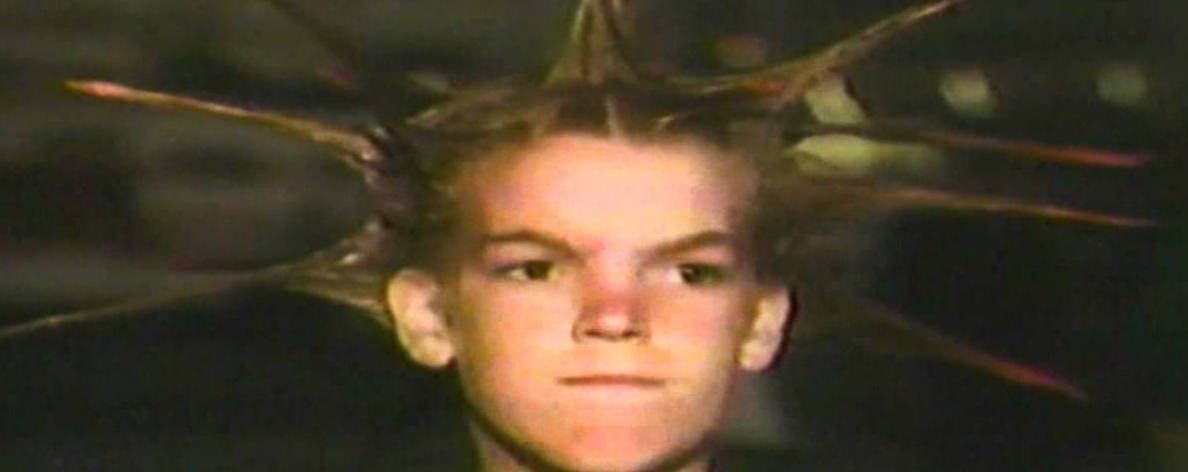

A short video shot in Toronto in 1983 captures the band’s live show in its heyday. Cal, sporting a soaped-up mohawk, stalks the stage like an apex predator, swinging the microphone and hanging over the stage’s edge to bait the crowd. His neck veins bulge as he screams. Pooch, the guitarist, and Rainy, the bassist, stand stock-still to either side of Cal, spike-haired golems, while the strobes flash behind them. Garry anchors the attack, pounding out a racing, relentless drumbeat. The camera cuts frequently to the crowd, which in its writhing resembles a human storm pattern.

At this point in its career, Discharge was hardcore royalty, the keeper of punk’s true flame.

It was a dangerous place to be.

When Discharge returned to North America three years later, in the summer of 1986, a new trend was sweeping the music world. All of the heat and light was focused on the Sunset Strip, in Los Angeles, on glam metal bands like Poison and Dokken. “Cock-rock” (as detractors termed it) was rock’s worst excesses made audible—spandex-clad and empty-headed, interested solely in partying and getting laid. But it was catnip to record label executives and ubiquitous on MTV. Underground groups of all stripes hopped on the AquaNet and cocaine bandwagon.

Glam metal was the antithesis of everything Discharge stood for. Bizarrely, though, Discharge had gone glam, too. Its new album, Grave New World, abandoned the brutal minimalism that had defined the band’s sound. The new stuff was twice as long, with hooks that sounded like Aerosmith outtakes and guitar solos best measured in geologic time. The lyrics remained substantive, tackling issues like drug addiction. Unfortunately, Cal delivered them in a nearly unlistenable wail, grasping at notes he couldn’t quite hit.

Moreover, the band had a new, markedly un-punk look: bird’s-nest hairdos, dangly earrings, mascara. The band photo on the album said it all: the anarcho-punks had become poodles with shiny, well-conditioned coats.

For the Rest of this thought provoking feature head over to The Appendix

Luther Blissett

December 13, 2014 at 11:19 pm

And yet… Grave New World is musically a very interesting record… Vocals aside.

See the last song, The Downward Spiral