One of the most insidious aspects that made Nazi death camps so “effective” when it came to genocide and mass slaughter was the calculated and regulated structure of the extermination process. Resembling a factory floor-style production assembly line, it is perhaps the clinical efficiency and disturbingly unique order in which the atrocities were carried out that still resonate so strongly in the world today.

What is seldom discussed in relation to this seemingly unique period of modern history is the fact that the Third Reich did not invent this dark peculiarity. Nazi concentration and death camps, were in fact, modeled on the Soviet gulags that preceded the Nazi party’s control of Germany and subsequent ethnic cleansing. What the Soviets essentially introduced in the early 20th century, the Nazis took to horrifying levels of near “perfection”. While the motives of persecution may have differed, (broadly and generally speaking, for the Nazis it was racial, while for the Soviets it was political – certainly there were crossovers and similarities in both regimes), the methods remained eerily similar in execution. For a country like Russia, the largest in the world, and particularly in the era in which gulags became synonymous with terror – following the Russian revolution, overthrow and murder of the Czar and his family, Civil War and subsequent establishment of Communism as the ruling and dominant political power – it seemed a system of mass slaughter was necessary, according to the twisted and paranoid minds of the Red Army leaders. Hence, the gulags.

While many films have dealt with or displayed the atrocities committed in both Nazi and Soviet death camps (Schindler’s List being possibly the most famous and obvious example), it is a film from 1992 that is perhaps most closely authentic, realistic and brutally honest in its portrayal of the process of extermination.

The Chekist (dir. Aleksandr Rogozhkin) was released at a curious time for a film dealing in the subject matter that it does. Two years after the Iron Curtain came down in Eastern Europe and Mikhail Gorbachev disbanded the Soviet Union, the film looks at the years following the Revolution, the Civil War years, before the Stalinist era and before massive areas of land were dedicated to gulag camps. It predates the Stalinist purges yet deals with similar purges of Russia’s intelligentsia, peasantry and anyone else with a differing point of view than that of the ruling leaders. As such, we see Russia coming out of one period of chaos and into another, before it became a massive and dreaded superpower, before the era where the grim man with the enormous moustache and steely gaze ruled an immense country with an iron fist. The Chekist is set during the time when Lenin and Trotsky’s Marx-and-Engels-based fervour resonated with a group of radicals who took what were essentially a few reasonable and noble ideas and turned them into an ideology that became a boot in the face of humanity. Most notable in reinforcement of this is this line from the film: “Revolution is not an idea. It is an organism.”

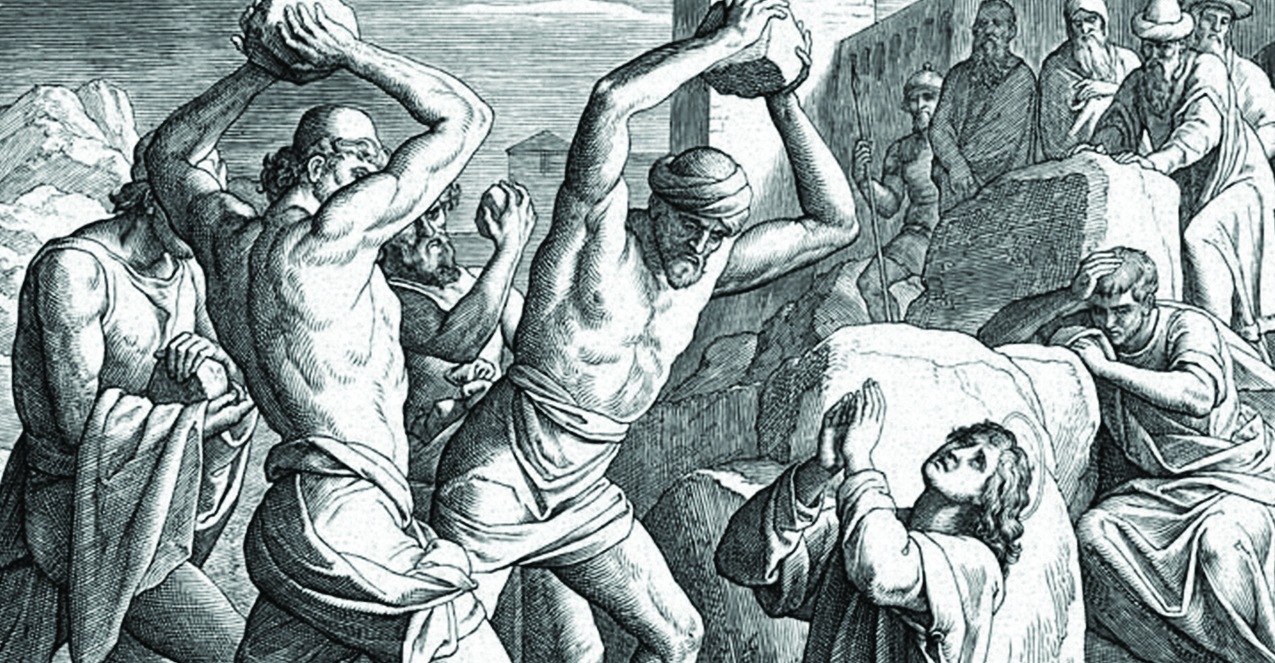

The film captures the disturbing monotony and routine that executioners in this dark period of Russian history laboured under. Orders from the head office are given, then carried out. Repeat ad nauseum. Scenes of organising groups of prisoners designated for death followed by murder followed by corpse disposal permeate the film. Graphic in nature, the film is unapologetic in its portrayal and resembles some of the post-war Italian Neo-Realism films in its almost documentary style approach. The titan of Soviet cinema Andrei Tarkovski’s influence is noted, with many scenes employing an ever-circling, ever-moving camera, offering a sinister and evocative meditation on the process of organising genocide. Characters appear lifeless and robotic throughout much of the film – people speak in slogans, rarely do we see a real human side other than from the unfortunate prisoners. During a scene as an execution is about to take place, one prisoner remarks – “So these are the doors to another world – without hinges,” offering a rare glimpse into the banned and prohibited world of spirituality. Perhaps most notable in the denouncement of Communism in the film, however, is the portrayal of the cleaning lady in the film. The cleaning lady, symbol of the working class – she is constantly treated like scum and disrespected, despite the idea of the death of class warfare and equality.

The Chekist is not an overly “enjoyable” film but its strength is in its gritty realism. As a satire it’s effective enough to have its messages be taken seriously and delivers in a poignant and unrepentant style. As an affront to the early days of Communism and its subsequent despicable offsprings, forms and perversions that have taken root throughout the world that have murdered, terrorised and imprisoned countless people in the name of a left wing ideology, freedom and “what’s best for…insert country here”, The Chekist is highly effective in this regard.

Sara Campos

October 15, 2014 at 4:02 pm

D: voy pen

Ricardo Díaz Medina

October 15, 2014 at 3:57 pm

Sara Campos