I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Martin Sorrondeguy on the phone from his family’s home in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. Martin politely agreed to let me interview him for Cvlt Nation and greeted me warmly over the phone as I interrupted some of his time from making chimichurri with his mom.

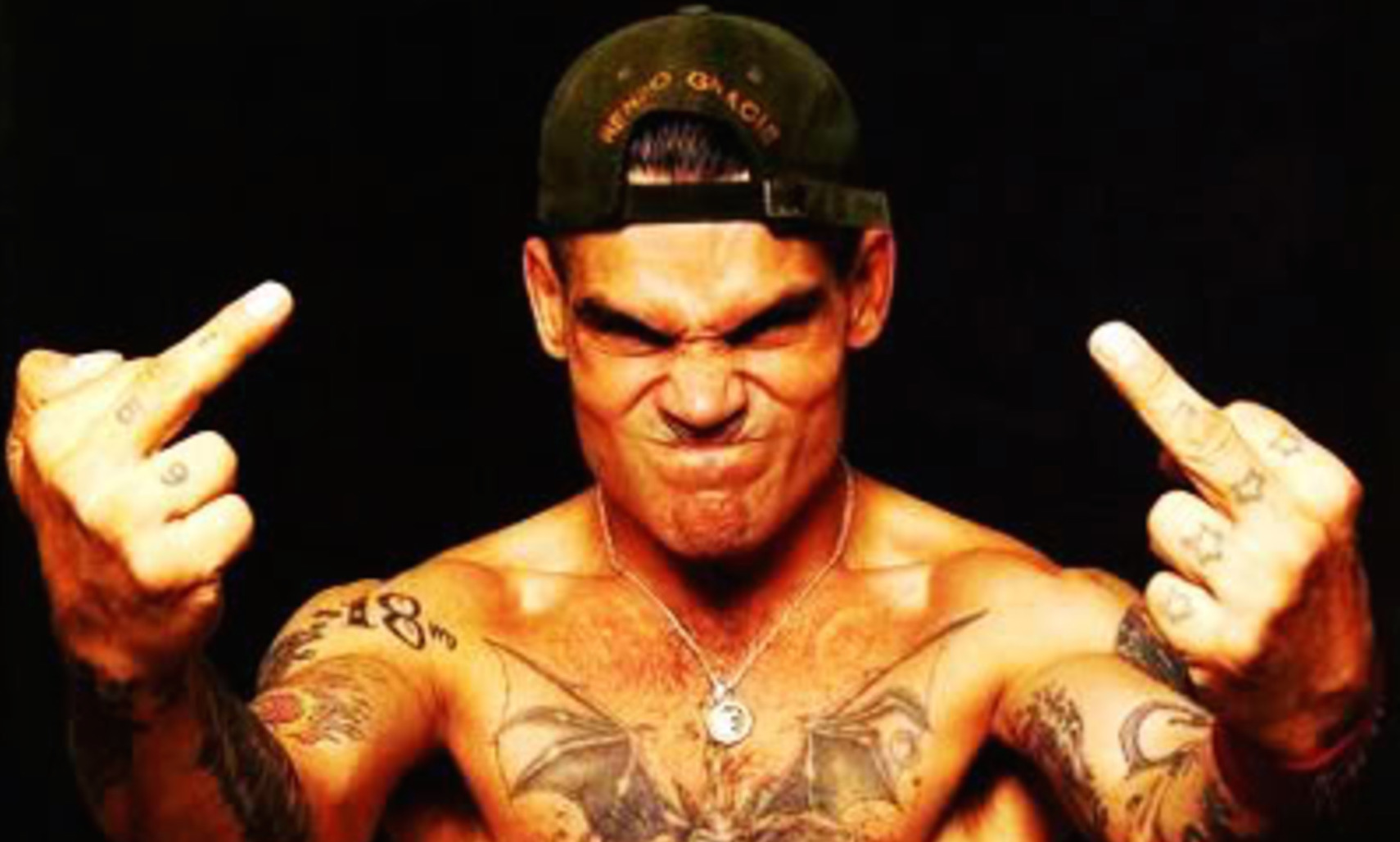

For many within the punk/hardcore community, Martin needs little introduction as his involvement in the scene has left a tremendous impact. Martin’s most visible involvement in punk has come through fronting hardcore bands like Los Crudos and Limp Wrist and through forming DIY record label Lengua Armada Discos; which throughout the years has served as a powerful venue for supporting and exposing Latino punk/hardcore bands.

Aside from his involvement with Los Crudos, Limp Wrist, N.N., Needles, and Lengua Armada, Martin has stayed active within the punk community through regularly contributing to Maximum Rocknroll, creating documentary films like Mas Alla de los Gritos: A U.S. Latino Hardcore Punk Documentary, and authoring a new book on punk/hardcore.

During our conversation, Martin and I talked about various topics, including: his upcoming book called Get Shot (pre-order the book here), what it was like playing in Latin America, a brief family history, the upcoming Los Crudos vinyl discography, and even his involvement in the early hip-hop scene as a B-Boy.

With that said, I was very happy to interview Martin. Now read the interview and let one of punk’s smartest and most creative minds impart some knowledge on you!

—————————————————————————————————

Can you talk a little bit about the book you’ve been working on and the upcoming Los Crudos vinyl discography that is coming out soon?

Martin: So the Los Crudos discography will be a double LP released by Maximum Rocknroll, which for those who don’t know, is one of the longest running underground punk zines in the world. So they’re actually going to release the discography and it will compile all of the studio works that we did and place them on two records. That should be coming out within the next six months and it’s something that we’ve been talking about and working on for a while.

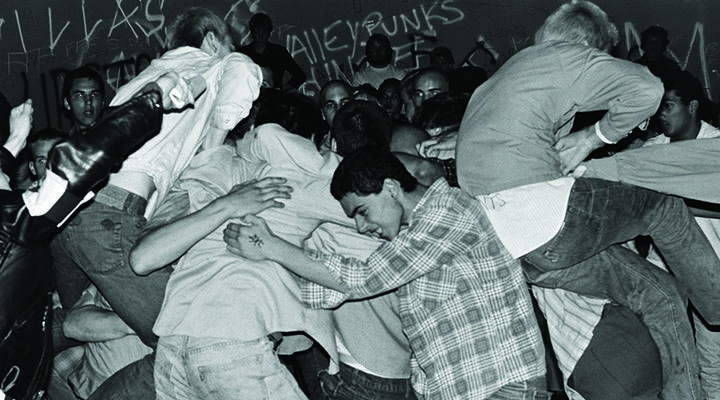

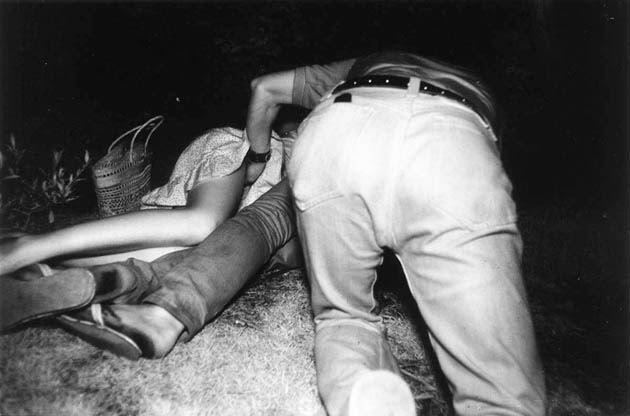

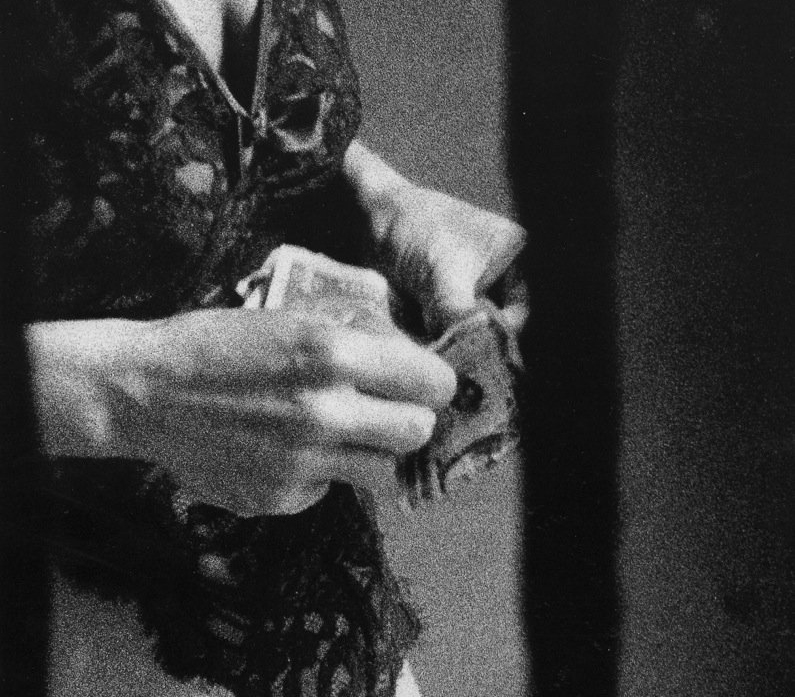

As far as the book project, there is a label called Make A Mess that approached me about re-releasing a photo book that I did that came out in Japan a couple of years ago. That book was really difficult to get here in the U.S. because it just didn’t have the distribution and was primarily sold overseas. Well they wanted to re-issue it but I didn’t want to release the same book basically because I didn’t want to step on the toes of the people that put it out. So I suggested doing an entire new book of photographs I had in my collection and they really liked the idea and we put together this photography book. The book is called Get Shot: A Visual Diary, 1985-2012 and it basically focuses on punk from live shows to portraits of people, and places that I’ve been to when we were on tour. So it kind of looks at everything. It’s like a visual diary that covers a lot of stuff. That will be coming out in the next four to five weeks. I’m actually going to be traveling a good chunk of this year in promotion of the book. We’ll be having exhibits and selling the book, so I’ll be moving around with it as well.

You just have everything in the book. That comment was made by somebody that wanted to say it’s about time there is a book about punk and it’s not just all-white figures and it’s really representative of the diversity that truly exists in this global punk world. I feel good about that, I think that’s great because for me punk was never just a “this type of person thing” or “that type of person thing”— punk really is about everybody. I think since the book displays that, it really is more aligned to what my vision of punk is. I’m glad that this book can support that idea.

Will there be any unreleased tracks or demos in the Los Crudos discography?

Martin: Well we had put a lot of that on the CD discography so there wasn’t really much of that for the vinyl discography for Maximum Rocknroll. I think the primary purpose with doing the discography was that everything has been out of print on vinyl for quite some time and there still seems to be a demand and people want to get it on vinyl. So that was the reason for doing the discography with Maximum Rocknroll. We actually wanted to do it as a way to help out Maximum Rocknroll because they’ve been going through tough times. For me, doing it on their label was pretty important because I’ve always felt that they’ve played a very important role in supporting underground DIY punk and hardcore music. So it made sense to do it on that label.

For sure, that sounds like a great plan to help support MRR. Someone mentioned before that there are probably more photos of people of color in the punk scene in your upcoming book than any other book has previously shown. So what does it mean to you to be able to be a part of documenting people of color’s involvement in the punk/hardcore scene?

Martin: Well for me, as a punk and as an artist, it’s just the way it turned out to be. When you’re documenting what you come into contact with or with what or who’s around you, I guess that’s what always is reflected in the body of work. So I ended up with just everybody. You have pictures of trips that I took to Japan. So that meant a lot of Japanese/Asian presence in the book. Of course, you have the Latino/Chicano presence just from touring Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Mexico, and all the Chicanos that are living here in the states. You also have a ton of white kids too though. You just have everything in the book. That comment was made by somebody that wanted to say it’s about time there is a book about punk and it’s not just all-white figures and it’s really representative of the diversity that truly exists in this global punk world. I feel good about that, I think that’s great because for me punk was never just a “this type of person thing” or “that type of person thing”— punk really is about everybody. I think since the book displays that, it really is more aligned to what my vision of punk is. I’m glad that this book can support that idea.

Cool. I think that message goes along with what you did in Mas Alla De Los Gritos as well since it does a great job of showing the Latino contribution to the punk movement. I’m a big fan of that documentary and I wanted to ask you a couple of questions about it. When did you begin working on Mas Alla de Los Gritos? Also, why did you start that project and what impact do you think it has had on the punk scene since it’s been released? Especially since it’s been pretty accessible through YouTube now.

Martin: It originally began as a photography project and I wanted it to focus mainly on the Latino/Chicano punk scene through still images. Well this project was a part of my college studies and it turned out pretty funny because one of the comments that was made as a critique was that one professor said: “You know I like the photos but, you know, it’s just so quiet.” And that was a comment that was made about the photographs, that there was no noise associated with them. You see these faces in the photographs but there is nothing coming out of them. Well I thought that comment really impacted my decision about where I was going to take the project next. I thought that this professor was absolutely right. It was too quiet so I went out and bought a video camera and I started video taping all of the shows and interviewing people. When Los Crudos went on their last tour, I took the camera on the road and I was able to go around and document more and more. I also had previous footage from Los Crudos’ tour from South America. So all of that came together and I ended up with about 80 or 90 hours of footage and I worked on editing to put the project together. It took about a good year and a half or so and I ended up with about a 30-minute documentary and that was released in either 1998 or 1999.

As far as the impact that it’s had on the punk community as a whole… well I don’t know. You know the video sort of took a life of it’s own. Copies got out all over the place and people bootlegged it and it eventually got to YouTube. I think that’s all great. People come up to me all the time and they tell me about the video all of the time. Someone actually came up to me and said “Hey I saw your video being shown in the Czech Republic at some show,” and I was like “Wow, well I wonder how that happened but that’s cool.” I mean the reaction has been extremely positive so I was excited for that.

It seems like Los Crudos, probably much more than any other Latino punk/hardcore, has had a much wider audience than any other Latino punk band during the 1990s and even up until now. It seems like a lot of other bands like KONTRAATTAQUE and Huasipungo never really got to that point of visibility that Los Crudos did. Why do you think that Los Crudos was different in this regard? And I say this because I’m sure most people in the punk/hardcore scene would generally recognize Los Crudos over a lot of the other Latino punk bands from that era.

Martin: I think one really important thing that needs to be looked as it that Kontraattaque never toured. Well when it comes to punk bands, a lot of the bands that started to tour became the bands that most people started to talk about. And I saw that with a lot of other bands. I remember when Spitboy did their first tour, all of a sudden people had shirts, patches, and everyone was all of a sudden talking about Spitboy. Now I think Huasipungo did one U.S. tour and they did like small trips but Los Crudos were traveling a lot. Los Crudos did at least three U.S. tours and then we would do other things like drive out to New York or do a string of shows on the east coast. We also did two different tours of Mexico. We went to Japan and South America. And all of that not just generated a lot of interest but also a lot of visibility. You know, I think that’s what happened. We would just travel a lot. Well now with bands like Tragatelo, Arma Contra Arma, and Kontraattaque; which are bands that me or friends of mine or Los Crudos members were involved in, many people don’t know them because we really never played anywhere or tour to the extent that Los Crudos did. Even with N.N., people don’t really know who N.N. are because we haven’t toured. Very few people know of that band.

How did Los Crudos find the time and the resources to tour so much?

Martin: Well when it came to resources, it was minimal. We really practiced the DIY ideology. We first created a decent local following that when we would play we could sell shirts and make shirts and it came to the point where we became self-sufficient as a band. We weren’t living off of it but when we had to do something like a U.S. tour, we would put aside money to buy more shirts and keep money funneling into the band to help us tour. No one in Los Crudos came from money. No one had money. We didn’t have mom and dad helping us out or pitching in money. We also had friends, like in Japan, a friend of ours put up some of the money to help us get there. Without that kind of help, we wouldn’t have been able to do it. If we had to do an out of country tour, we became good at cutting expenses by doing a good month or two of touring in the U.S. to help make a little bit of money to be able to do the European or Japan tour. That’s sort of what Limp Wrist does now too. We play a bunch of shows here before we leave anywhere because it will help cut a huge chunk of the expenses.

Like I remember with Sin Orden, when I first met those kids and got them their first show I told them “Let’s make some shirts.” And they were kind of like “What?!” Well it was simple, we got a piece of contact paper and put it on a silk screen and made their first twenty or thirty shirts very easily. Just to try and generate them a little bit of money to possibly do something as simple like a recording or something along those lines. So that DIY mentality was what we practiced. For us, being self-sufficient was crucial. It was also really important to us to pass on that type of DIY idea to a band like Sin Orden was really important to us.

What was it like when Los Crudos went into Latin America? What were some of the most memorable moments and experiences from being there?

Martin: Well the response was overwhelmingly positive. People were very excited that we were coming out. I think that there was kind of this type of confusion or even mystery behind us. People in Latin America were like “Who is this band from Chicago? Really? The U.S.?” I remember a friend from Argentina told me that he gave someone a tape of ours to someone and it blew his mind that we were from the United States. Like he couldn’t believe it. I think that sort of piqued a lot of people’s interest in Latin America. By the time we ended up going to South America, we had already existed as a band for like 5 or 6 years. People knew of us and they had our music by that point. The response was really awesome.

The first time we went to Mexico, we were met with a lot of positive reactions. Sometimes there were a lot of people that didn’t know what we were about. I guess sometimes people thought we were some sort of band that was just trying to make some money. But we went there without that type of attitude. I remember once this kid came up to me and started talking shit saying we flew over there and I was like “Dude, we just drove here from Chicago. We didn’t fly anywhere.” He seemed confused and just walked off. So I guess some people at times thought we were some sort of rock n’ roll band but that wasn’t us. We weren’t there to make money or anything like that. We were doing it the DIY way and traveling as inexpensive as possible. But overall the response was amazing. It was great.

Before I got into punk, I was involved in this really early B-Boy scene. And that sort of helped to ground me and be okay with who I was since there were all these kids of color that were into this really early hip-hop scene. That was a really good thing and then punk pushed it even further as it was more politicized.

What was your most memorable show in Latin America?

Oh, wow, I don’t know, that’s a tough one. There were so many cool shows. I remember we played outside in Mexico like in the middle of a busy street. There was a patch of grass on this median between two streets. There was this police traffic watchtower there and we played there. All these punks showed up with a generator and people brought the pieces of drums. Someone brought like a tom and a snare, and someone else brought cymbals. Every band played on the same kit the entire night. They were stealing the electricity from the city. People were like dropping their sweaters and jackets on the ground because people were getting shocked while we were playing. It was like the rawest and most punk show I’ve ever played in my life. It was amazing. It really was phenomenal.

I think another memorable show would be in Mexico that we played where there was this massive pit. I have a whole video of the beginning to the end of that show. Basically the show was a benefit for this radical anarchist library in Mexico City but a lot of people didn’t want to pay so about 600 people ran through the door and basically came in for free (laughs). It was kind of crazy. I have it all on video, they were like smashing and throwing rocks and bottles and cars got smashed up outside. It was kind of crazy. There were a lot of amazing shows. We played in Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and a lot of other places.

So you grew up in the Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago. How did your family end up in Pilsen and what was it like growing up there and being into punk?

Martin: My relationship with Pilsen is really weird. When we first got here there weren’t many Latinos living in this part of Pilsen. It was a pre-dominantly Italian and Polish area. We went to a school where there were maybe two other families that were Latino. It was weird. As the years went on, the neighborhood started to change. At my school, they didn’t like us to speak Spanish. They didn’t want us to speak Spanish. So when they had new kids come in, they had me do this really weird and twisted thing where they would have me translate to the kids and tell them that they shouldn’t speak Spanish anymore. That they had to speak English. And it really sucked to be utilized in that way. There was this underlying message that we had to assimilate into this different culture and that we had to surrender who we were. So I really had a lot of battling going on as a young kid growing up in this neighborhood. Battles with identity and all of that.

Before I got into punk, I was involved in this really early B-Boy scene. And that sort of helped to ground me and be okay with who I was since there were all these kids of color that were into this really early hip-hop scene. That was a really good thing and then punk pushed it even further as it was more politicized. Before punk I was rejecting a lot of things because the “old” neighborhood was making me reject a lot of things. I had to come to terms with who I was, who we were, where we were from, and how things played out when you were from somewhere that was different. So punk helped me really reclaim who I was. That’s a big part of what Los Crudos was about. It was a reclamation and saying I don’t care about what other people think. Like if people were bothered that we spoke Spanish and that they “didn’t get it,” well that was alright. You don’t have to get it because we get it.

So my relationship with Pilsen is weird, I guess. I come back to the neighborhood and the neighborhood is a very different place now. There’s a lot of history here and a lot of weird shit going on too. It’s been heavily gentrified in the recent years and that’s kind of something that’s happening in big cities all over the place. I have a sort of love-hate relationship with the area for so many different reasons.

How did your family end up in Pilsen, if you don’t mind me asking?

Martin: Not at all. You know there was a program in the late-1960s. They basically opened the U.S. and Australian borders to Uruguayan workers. My dad was offered the opportunity to come to the U.S. or go to Australia to work. Well my dad knew some old buddies from the barrio that came to the U.S., specifically Chicago, so my dad decided to come here. So he went and he’d send money to get the rest of the family when he could. So my dad came over first and that’s what happened. A lot of Uruguayans were going to New York but my dad, because of his buddy, ended up in Chicago.

So how old were you when you actually came to the states and what do you remember about life in Uruguay?

Martin: You know, I was so young; I was about two years old so I can’t really tell you anything about Uruguay because I can’t remember anything. My only recollections of Uruguay really come from here in the United States through hearing about how life was in Uruguay through my family. 1984 was the first time my family started going back. That was right at the end of the dictatorship. For years and years we didn’t dare go back. It wasn’t until that time in 1984 that it was the first return for us and it wasn’t until 1990 that I went and I stayed for 6 months. That was when I really got to experience life in Uruguay first-hand. It was a phenomenal trip, you know? As far as the history, it was just a dark period for the country because so many Uruguayans had left and couldn’t go back. It wasn’t until there were political changes and the dictatorship ended that people started to return.

What were those six months like when you finally returned to Uruguay?

Martin: I mean there are so many aspects of it. It was the first time that I was around a whole country of people that spoke like we did, with our accent, and that was huge for me because we sort of felt really isolated. Most of my friends in the neighborhood were Mexican or Puerto Rican or something and they had different accents. It’s not like we had a neighborhood of Uruguayans here, you know? It was the first time where people sounded like me and that was crazy. Then there were other things, there was a lot of history there, it was meeting people, and meeting people who grew up with my parents and meeting cousins that I had never known. It was a heavy experience, I came into something that was so much a part of me even though I was so far away from it, you know what I mean? So it was kind of like reconnecting a lot of things. It was a personal familial thing, a cultural thing, a language thing, and a political thing. You know, my aunts would say: “Martin, we know you like to go out and talk to people but be careful what you talk about. Things have changed but things haven’t changed that much.” You know, kind of warning me. It was a very big and important trip for me. I came back and based a lot of Los Crudos songs based on all that kind of stuff that I had experienced in Uruguay. So I kind of joined that experience with my experience of being from Chicago and having this sort of Americanized perspective of a Latino Americano in the U.S. and as an immigrant.

When we came back to Pilsen a few months back and we went to a show, some kid was like “Who is that? Your bodyguard?” and I was like “No, man. That’s my man.” And he was like “What?!” And I said “That’s my boyfriend. That’s my man. That’s how we roll.” The kid was kind of in shock. And his friends were like going “Dude, shut up!” But that’s just the way it is.

Earlier you mentioned your struggle with identity and reclaiming it. What do you identify as? Latino, punk, gay, Uruguayan?

Martin: [laughs] That is a very good question! I don’t like putting one thing over the other, you know? I am who I am and there are so many categories. I think we have this human goal where we want to figure everything out and everything has to be laid out for us. I think that’s complicated. Oh, man. It’s like, what is it that you want to put yourself out there as to people and market yourself as? On the other hand, what do people see first? I don’t know what people think of me when they look at me. I can start throwing stuff out there but I don’t know, it is so complicated. I am so many things. I like that things aren’t so easy to figure out. I like when things get really twisted. There is something really powerful in that, you know? When I walk with my partner and I go into a punk show and he’s with me and people are like “Who in the hell is this?” For example, when we came back to Pilsen a few months back and we went to a show, some kid was like “Who is that? Your bodyguard?” and I was like “No, man. That’s my man.” And he was like “What?!” And I said “That’s my boyfriend. That’s my man. That’s how we roll.” The kid was kind of in shock. And his friends were like going “Dude, shut up!” But that’s just the way it is. I like the fact that stuff like that fucks with people because everyone wants to compartmentalize everybody and I like fucking breaking all that stuff. I like tripping people out. I think the important thing is if you’re a good person or if you’re a shitty person though. That’s what really is important.

Okay, so I don’t want to take too much more of your time so I will start wrapping this up. What are you listening to right now and who are some of your favorite bands at the moment, punk and non-punk bands alike?

Martin: Well I do work at MRR, so I have my top ten every month. There’s really good stuff that’s always coming out. As far as old stuff goes, my mom loves tango music, so I love tango music and grew up listening to lots of it, Tita Merelo. Olga del Grossi, Julio Sosa, some Astor Piazzolla I love so much music Chavela Vargas, as for recent punk stuff D.H.K. Wiccans, Creem, Neon Piss, Brain Killer, Stripmines, Criminal Code, Violent End, Ropes, Yadokai, Crazy Spirit, Speed Kills, Criaturas, Ilegal, Sadicos, Bukkake Boys, Brown Sugar, Sudor, Orden Mundial, Nemisis, Destino Final and tons more.

Is there anyone from the punk world that you feel haven’t been adequately recognized that you want to mention or give some props to?

Martin: The thing is that there really are so many people because it’s such a large scene with so many people. The thing that is kind of unfortunate, and this is just how things are and it is kind of sad, is that the majority of the people that get recognized in punk comes through the musical aspect. So people only talk about people in bands most of the time, right? But the reality is that there isn’t enough representation of the people who are the real glue of it all. So you’re talking about people who do fan zines, people who just go to shows that aren’t really in bands but that they might make flyers or do zines. People that just kind of support and go to shows all the time. There are tons of people like that. Even when I did Mas Alla de Los Gritos, there are people that I interviewed that weren’t in bands or people who were just participants in the scene aside from bands. I think with a lot of documentaries coming out and all of these movies, the focus is always on people who are in bands. I think that’s a huge error and it’s not an accurate representation of what it’s all about because there are so many people involved. Like even the people who just do distros or something, all of that is important. There are all kinds of cool projects that are being done that really look at all of the people.

Okay, any new projects/shows coming up with Limp Wrist, Needles, N.N., or any other bands coming up?

Martin: Okay so Needles is working on a new record. We’re going to be doing a record with Iron Lung. We’re not sure yet, it may be a 12”. Both Limp Wrist and Needles may do a tour of Australia this January. Limp Wrist may play a couple of shows before we leave, most likely on the east coast but I’m not sure yet. We may go out that way. N.N. has been on hold for a while and I’m not sure what may happen with that band for a while. That’s about it.

New Comments