Written by: Yohani Kamarudin

Written by: Yohani Kamarudin

Photos by: Karl Colonnier

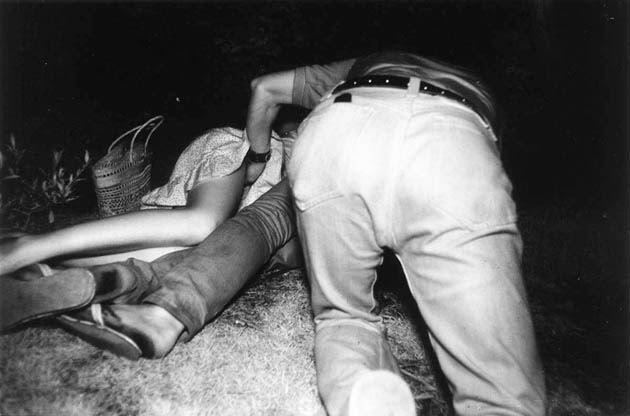

The air is thick with a noxious fog – a mixture of haze and the smoke from burning tires. The toxic fumes mix with the stench of rotting meat and decaying vegetables. Trash lies heaped all around, not as a result of carelessness but simply because this is a garbage dump. It is also the home and workplace for a group of Burmese ‘Karen’ refugees and their children.

Mae Sot is a Thai border town. Sharing a border with Burma to the west, the district is a hub for trade between the two countries – much of it illegal. Gemstones, teak and drugs flow through Mae Sot daily. Yet people trafficking is also a major problem, with many Burmese people fleeing starvation, persecution or war in their homeland.

“Maybe it is the naivety of a child,” says filmmaker Sascha Schöberl, who is striving to make a documentary about life at the dump. “But still they are able to find happiness under the worst living conditions you can possibly imagine because they turn all this trash around them into an adventure park. And the trash turns into treasures. They invent games with old magazines and stones. They deal with this tragedy with such creativity and grace. It is so inspiring and impressive. These small little children taught me a lot.”

Life in the dump is grim. Those old enough help their parents to sort through the waste dumped throughout the day by garbage trucks. But before reaching the dumpsite, the truck stops at an official recycling center. Here, employees – who are also refugees – remove the most valuable items for recycling: thick plastics, glass, paper and tin. Those who live and work scavenging at the dump only get the leftovers.

As you’d expect, scavenging a living on a dumpsite is a dangerous job. Obviously, the smell is horrific. But the fumes, which can cause respiratory diseases, are not the only hazards faced by local dump dwellers. Pieces of glass, rusty metal and other sharp objects lie ready to scratch and cut. And besides the threat of tetanus, there is also the danger of untreated wounds festering in these unsanitary conditions. Malnutrition and sickness are commonplace; so too are skin diseases.

Dump dwellers eek out a living selling what they find to factory owners. Mia Thein, 29, makes about 90 baht (less than US $3) a day selling her ‘treasures’ to a factory that will recycle the used items into sellable goods. It’s not a lot of money, even here, when food for a family costs the equivalent of around US $2 a day.

The families would pay less for food if they could buy groceries in bulk, but then there’s the risk it will be seized by the police, who occasionally raid the dumps. One family had their chickens taken during a raid. Even the bags of trash the locals have collected are in danger of being confiscated and sold on if left unattended.

Not all Burmese refugees living in Mae Sot work at the dump. Most of the town’s 80,000 or so refugees work in one the 200-plus textile factories. But life is still difficult. Without Thai legal papers, rights and protection, the refugees are ripe for exploitation by unscrupulous businessmen and criminals.

Those who campaign for better rights for illegal workers also face the threat of violence from gangsters; in 2004, one Danish labor activist was stabbed. Meanwhile, attacks on workers themselves are more frequent, with the charred remains of murder victims apparently not an uncommon sight along the border.

“Every human rights violation on the planet is there in its worse element,” says Reuters photographer Damir Sagolj, who is a regular visitor to Mae Sot.

To understand how people could possibly live and work in such seemingly unbearable conditions, it’s necessary to learn a little more about the situations from which they’ve come. The refugees, who belong to Burma’s Karen minority, are fleeing from direct military attacks, forced labor, enslavement, and the destruction of their homes and farms.

One dump worker recounts being forced to work as a Sherpa to government soldiers, during which time three of his children died from a lack of proper nutrition. “There is no war in Thailand, and at least we have a little bit to eat,” he says of his new home.

It may be preferable to a war zone, but living in Mae Sot is still no way to grow up for a child. “When I talked to the parents about the future of the children, often I would have to stop because they started to cry,” says filmmaker Schöberl.

“The parents deal with their situation by thinking from one day to another, one meal to another. There is no perspective, they would love to dream for the children to get an education, go to school and get a great job. But they don’t see that this is possible and so they block it out. And once the children get to this stage too, they don’t see that their dreams are actually realistic, they become bitter and sad.”

But there is some hope. People have begun to take note of the plight of Mae Sot’s refugees. There is a charity school at the dump, the Sky Blue School, which teaches those children lucky enough to have the time to go. Another organization, The Best Friend project, set up by two Burmese monks, is also making a difference.

The Best Friend project works to provide basic needs and services to the refugees of Mae Sot and the dump. They distribute food and medicines and try to relocate dump dwellers to better locations. Unfortunately, one of the monks, Ashin Sopaka, is currently under Burmese military surveillance, and his movements have been limited. Still, he remains positive and hopes to build a library.

Slowly, the situation appears to be improving at the Mae Sot dump, thanks in no small part to the efforts of The Best Friend project. “Every time I go there, I see people smiling,” says photographer Sagolj. “At night, they light candles and sing, they eat and socialise and basically look the fun side of life. Nobody forced them to live there but they don’t want to go home.”

Ultimately, it seems like the long-term solution would be an improvement of the political situation in Burma itself. “These people are not only on the landfill because they are poor,” says Schöberl. “They are there because of the political situation inside Burma. If Burma would be free and if there would be peace, these people would not be on that landfill.”

New Comments