While many historians explore the history of nations and kings, in 1974, the French historian Philippe Ariés explored what may be the sole constant in human existence: death. In a series of lectures entitled “Western Attitudes Towards Death” 1, Ariés contends that the perception and reception of death reflects the changing understanding of the self in relation to the world, from a life fated to death in the Middle Ages, to one in deep denial of its own mortality in the industrial world.

Death in the Middle Ages was what Ariés referred to as “tamed death” 2. Death was not tamed in the sense that it was avoidable – clearly – but that its existence was understood, accepted, and prepared for: “death was simply a thing” 3.

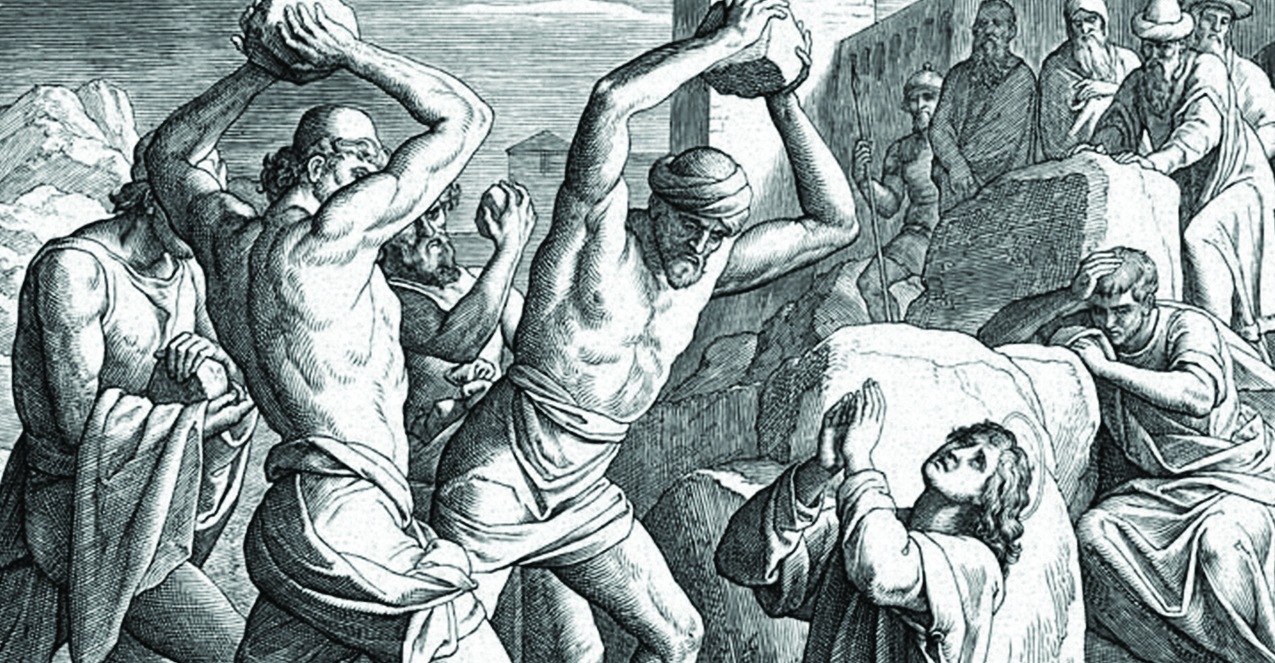

For Ariés, death in the Middle Ages was firmly in the domain of the dying, who organized their final moments, performing the ritual gestures of death in public. “The old attitude,” he argues, “in which death was both familiar and near, evoking no great fear or awe, offers too marked a contrast to ours, where death is so frightful that we dare not utter its name” 4. The Middle Ages were so comfortable with death, Ariés contends, that the living and dead existed side-by-side, most manifestly in the cult of the saints, where physical remains were venerated 5.

In the eighteenth century, however, Ariés sees a shift from loathe acceptance, away from even fear, to a “dramatization” of death, in what he calls “the romantic, rhetorical treatment of death” 6. Death became something sublime: beautiful and terrifying all at once. The solemn event of death, which Ariés identifies as the pervading concept for approaching on a thousand years, was pushed aside in a tide of emotional upheaval; robbed of its banalities, death became a spectacle of emotional turmoil, of despair.

The final period of Ariés’ study, leading to contemporary culture, is the culture of “forbidden death.” Whereas death was familiar and accepted from the Middle Ages through the nineteenth century, Ariés argues that industrialization has alienated western culture from the great constant of human life; “the disturbance of those close the dying person – the disturbance and the overly strong and unbearable emotion caused by the ugliness of dying and by the very presence of death in the midst of a happy life, for it is henceforth given that life is always happy or should always seem to be so” 7. Death is displaced from public, from the home, and condemned to secluded hospital rooms away from polite society. Following death, the body itself is even alienated from its living state, transformed by cremation into process remains “forgetting it…nullifying it,” Ariés notes.

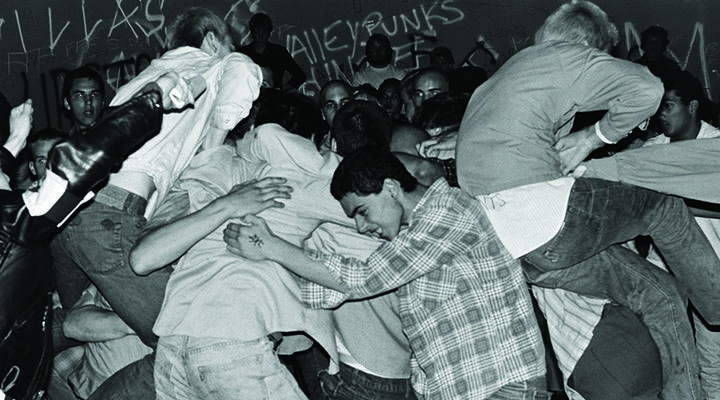

Ariés, in conclusion, asks whether there is a “permanent relationship between one’s idea of death and one’s idea of oneself? If this is the case, must we take for granted, on the one hand, contemporary man’s recoil from the desire to exist?” 8. If his thesis holds true and western society is aggressively prejudiced against acknowledging death, it has failed to contain this recognition entirely. As this site’s readership well knows, the grotesque image of death holds a vibrant place in the imagination of subculture scenes, where the taboo of death is blatantly ignored. While drawing primarily from the nineteenth-century romantic image of death, the image of death in underground music and art is certainly as varied as any of the periods which Ariés investigates. Perhaps the existence and proliferation speaks to a greater estrangement from western industrial (and post-industrial) culture; while our society is undoubtedly biased against death, our numerous subcultures cannot or will not ignore the sole universal truth of our deaths.

References

1. Originally a series of lectures entitled Western Attitudes toward Death, Ariés would continue to revise and expand his argument into the full-length or simply lengthy study The Hour of Our Death. See: Ariés, Phillippe. The Hour of Our Death: The Classical History of Western Attitudes Towards Death Over the Last One Thousand Years. Translated by Helen Weaver. New York and Toronto: Vintage Books. 1981.

2. Philippe Ariés, Western Attitudes toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present, tr. by Patricia M. Ranum, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1974, 2.

3. Ibid., 7.

4. Ibid., 14.

5. Ibid., 15 – 16.

6. Ibid., 56.

7. Ibid., 87.

8. Ibid., 106 – 107.

New Comments