Today we are bringing you a fascinating conversation between Locrian‘s Andre Foisy and Horseback‘s Jenks Miller. The new album by Horseback, Half Blood, will be dropping May 8, 2012, via Relapse Records…

André: Before Half Blood, I would consider The Invisible Mountain to be your last proper Horseback album. How do you feel that your project has changed since you recorded and released The Invisible Mountain?

Jenks: Forbidden Planet was recorded a month or so after The Invisible Mountain. Because Forbidden Planet first saw a (very limited) cassette release on Brave Mysteries (other formats were scheduled on other labels at around the same time but never materialized), it tends to get overlooked in a time-line. There does seem to be some confusion over when these records were recorded and released, so maybe I should provide a quick discography for Horseback’s recordings, then I’ll come back to your question.

Full interview after the jump…

Impale Golden Horn: recorded 2005-2007, released 2007

The Invisible Mountain: recorded 2009, released 2009

Forbidden Planet: recorded just after TIM in 2009, released 2010

New Dominions EP (with Locrian): recorded 2010, released 2011

A Throne Without a King (with Pyramids): recorded 2011, released 2012

Half Blood: recorded 2010-2011, released 2012

(There are some other EPs and splits in there, too, including the 7″ split with Locrian on Turgid Animal. A more or less complete discography is available on Horseback’s website, horsebacknoise.com if anyone is really interested.)

On to your question! Well … first, a little background!

A lot has happened since The Invisible Mountain, and I guess Horseback’s intervening records don’t really sound like that one. In fact, on the surface, many of our releases may seem to directly undermine previously-established stylistic concerns. I work to ensure that I don’t fall into the trap of maintaining style over substance, i.e., writing with any specific genre or audience in mind, so that the project remains a pure and vital creative outlet for me. On a conceptual level, this project is about a process of self-discovery and transformation, and I hope the records reflect that process.

I’m very interested in abstract sound (more like obsessed with abstract sound). John Cage’s theories of indeterminacy, and what is sometimes called spontaneous composition, have played a role in all of my work in this project. The Invisible Mountain is the least abstract of all Horseback’s records, insofar as most of those songs use riffs derived from blues and rock musics; the records following that one have all employed a more abstract vocabulary and involved a greater degree of indeterminacy, at least in their initial stages. The cool thing about indeterminacy is that it doesn’t exclude intentional forms; rather, it describes the set including both intentional forms and unintentional forms. From this perspective, there is really no contradiction in placing a blues riff next to more abstract textures, for example, or in combining those things in various shapes. (Is this the best way to communicate these ideas?? Does effective communication of these ideas even matter to the listener? It probably shouldn’t. Why bother with these interviews if it shouldn’t?)

The walls separating music genres — separating different approaches to composition — came down in the mid-twentieth century; those of us working in popular music forms are still playing catch-up! (On that note, it’s always amusing to me when folks who love modern visual art, Picasso or Pollock of whoever else, can’t wrap their heads around abstraction in music — which abstraction includes so-called “harsh vocals”, which are simply a different texture produced by the human voice. The distance between clean singing and so-called harsh vocal textures is really no greater than the distance Dylan traveled when he plugged in an electric guitar.) Abstraction puts you in touch with surreal combinations. These combinations are necessary to apprehend the modern world.

OK, now on to your question for real!

Horseback was founded on a relatively abstract musical language with Impale Golden Horn, then experimented on The Invisible Mountain with metal riffs and textures (riffs from blues and rock musics, textures from Satan), before diving further into abstraction. Half Blood combines a riff-based approach with a more abstract approach. Importantly, I don’t see any of this as a linear development. All these records would’ve been created simultaneously if I were more than one person and/or had a lot of money. But what can you do? There are always limitations.

André: Great answer. It doesn’t seem like a linear trajectory from The Invisible Mountain to this album, but why choose to put these songs on the album? Why choose these musicians to work with on it?

Jenks: Each record is largely shaped by whatever sounds I happen to be playing with during that time. Often, that includes some stuff that’s come from sitting down with a guitar or bass, and other stuff that’s come from raw sonic experiments that either exist on their own, or that I can shape into a composition. The musicians on the record are part of Horseback’s live lineup (which is John Crouch on drums, Nick Petersen on bass, and Rich James on guitar).

André: Ok, so how do you go about working with these musicians? Do you give them the concept of the track and let them interpret it?

Jenks: I write pretty much everything on my own, usually starting with a central bass riff, and we practice to make it work in a live setting. Sometimes we adjust the arrangement so it comes across better live.

André: You’ve stated that apocalyptic violence as a metaphor for change is one of the main Horseback themes across different releases. Could you elaborate on what you mean by change and tell us how this theme emerges on Half Blood?

Jenks: This project is concerned with self-discovery and transformation. Half Blood delves into alchemy very explicitly, but all the records have explored these themes one way or another. To achieve any sort of transformation, we must destroy a previous form, or at least dissolve our idea of that previous form as a pure, immutable thing. This is clearly where the metaphor of apocalyptic violence comes in. However, the way we understand “the apocalypse” has been confused in our society, like many things have been confused, by a literal interpretation of Abrahamic religious doctrine. An apocalypse is not a single, violent conflagration, wherein the chosen few ascend to heaven and the rest live out their sorry existence here on a scorched earth. Similarly, an apocalypse is not necessarily a violent conflagration in a more secular sense of “total war,” wherein survivors are left to wander a desolate landscape imagined by video-game developers. A literal understanding of these ideas, whether preached from a pulpit or sold to frustrated teenagers as a role-playing game, is just shtick; it misses the real point of the apocalypse, which has been there the entire time, both implicit as a metaphor and explicit in the root of the word itself, from the Greek apokálypsis, meaning “revelation.” An apocalypse is a revelation. In the wake of this revelation, we see ourselves in new light. We have the opportunity for reinvention with new knowledge. Change is not something to be feared. But no one should take my word for any of this — folks should do their own research!

André: I find it fascinating how artists change over time. Sometimes musicians change and learn from the things that they don’t like as much as the things they like. Rejection of ideas plays as much of a role in their work as the endorsement or redeployment of other ideas.

Can you describe your creative process for this album?

Jenks: I treat music like a job, which means I work on writing and/or recording for as much time every day as I can (while maintaining space in my life for jobs that actually pay the bills, and for family). So my creative process is very much a daily practice. It has become a spiritual thing for me, a time when I can allow my mind to go where it needs to go in order to be fulfilled. This means that I nearly always have a lot of very diverse material I’m working on simultaneously. At some point, I develop an idea or concept for a particular record, which allows me to decide which material might fit into a narrative, and which material won’t. That way I can organize the chaos just a little bit, piecing together the parts that relate best to each other. This leaves space for collisions to occur without too much conscious direction. Such unconscious collisions often lead to interesting combinations that I can then explore and develop more fully.

André: When you say that you treat making music like a job, I understand that to mean that you’re taking your music very seriously and not like drudgery. Is it difficult for you to approach your craft like this? Why/why not?

Jenks: I don’t find it difficult. This process seems to fit my personality — My best work comes when I’m completely immersed in what I’m doing. The difficult part is making time for other things, like a paying job.

André: Is recorded music like whale blubber? [Reference below]

“I think records were just a little bubble through time and those who made a living from them for a while were lucky. There is no reason why anyone should have made so much money from selling records except that everything was right for this period of time. I always knew it would run out sooner or later. It couldn’t last, and now it’s running out. I don’t particularly care that it is and like the way things are going. The record age was just a blip. It was a bit like if you had a source of whale blubber in the 1840s and it could be used as fuel. Before gas came along, if you traded in whale blubber, you were the richest man on Earth. Then gas came along and you’d be stuck with your whale blubber. Sorry mate – history’s moving along. Recorded music equals whale blubber. Eventually, something else will replace it.” –Brian Eno

Jenks: I sure hope Eno’s wrong here. His comments seem very cynical to me, considering few people would even care about his thoughts on the matter were it not for his recorded music. And as far as his economic argument is concerned, it’s totally off the mark. There’s still plenty of money generated by music and other creative content — it’s just that there’s a new set of middle-men between the artist and the consumer. Paradoxically, these new middle-men are more present but less visible than they were in the age of the major record labels — Google itself is one of them. It’s no secret that aggregator sites like Google depend on content they didn’t actually generate in order to draw traffic. People still want their whale blubber. It’s still a matter of ensuring that content creators are fairly compensated for their work; in this regard, nothing’s changed.

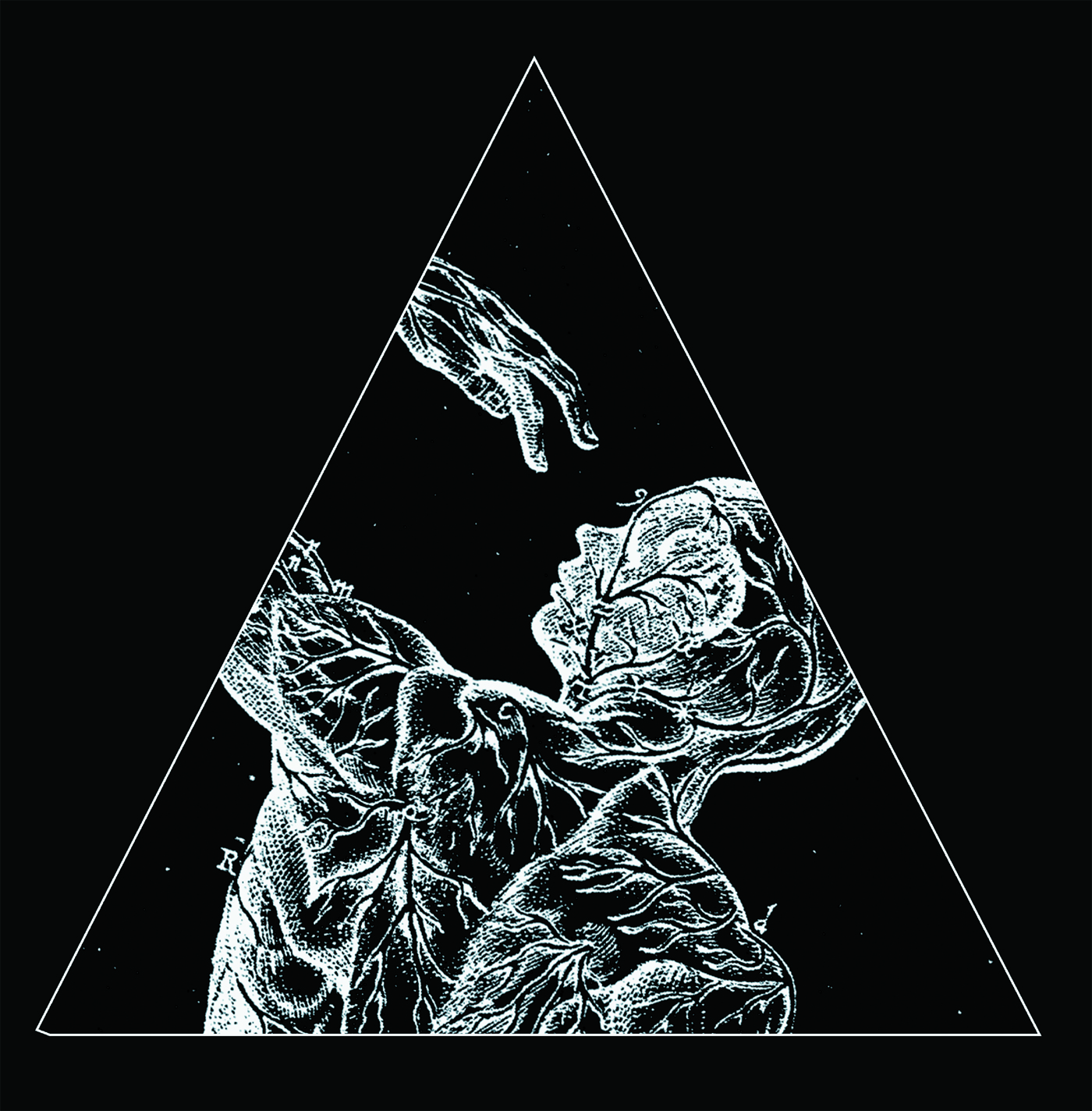

André: What can you tell me about the artwork for the release? I expect that Denis Forkas Kostromitin made the artwork specifically for this release, right? Does the artwork tie in with any of the lyrical themes on the album? If so, then how?

Jenks: Yes, Denis worked out a variation on the tauroctony for the cover, which introduces the mythical thematic language used on the record. The lyrics invoke a constellation of ancient deities as characters in an alchemical drama about hybridity, impurity and evolution. Denis has written an article about the creative process behind his image, which article will be posted soon, so I don’t want to step on his toes. More information about Denis’ art in general can be found at his website, denisforkas.com.

André: Did you work closely with him about the theme for the album though?

Jenks: The themes were already in place when Denis and I started talking about the cover art. Denis suggested ways in which the tauroctony might enhance those themes. His contributions always allow me to look at a record in new light, and are very inspiring because of this.

André: What about the lyrics? What came first, the lyrics or the music?

Jenks: The music came first. Lyrics and vocals are almost always the final elements.

André: Is there anything about this release that makes it particularly special to you?

Jenks: Yes, it feels like a synthesis of the various sounds and approaches used on past records. Now that this record has been distilled down and released into the world, I realize it’s a sort of summation of all the stuff I’ve attempted in this project up till now.

André: How do you approach Horseback, as a project, differently than you approach your solo material, or the material that you present as “Jenks Miller?”

Jenks: There are no set rules … sometimes lines get blurred. In general, the solo material relies more exclusively on improvisation. There’s less intervention in the later stages of composition, less of an attempt to exert a conscious influence on the direction. As a result, the solo stuff often feels more spare and “open,” while the Horseback stuff feels more dense and layered.

André: What’s your favorite Stooges album and why? [My favorite is Metallic K.O.]

Jenks: Funhouse, no contest. Why? It boasts some of the best-ever rock songs: “TV Eye,” “Loose,” “Down on the Street,” “1970.” It’s the most appropriate production they ever got: sounds are raw, but clear and powerful. Hypnotic riffs. Everything grooves. Pure id.

New Comments