Hello Jenks, thank you so much for doing this interview. How is everything in the Horseback camp?

Hello Jenks, thank you so much for doing this interview. How is everything in the Horseback camp?

Great, thanks Bryan.

The Invisible Mountain was the album that really put Horseback on the map, and you’ve released a lot of material since then. Your offerings on splits and collaborations since that release have been very different sonically. Did you intend to distance yourself from the sound of that record a little bit to avoid repetition?

I try to keep the process open. I’m not as concerned with whether or not I’m repeating myself as I am with pursuing ideas as they come. I try to avoid molding these ideas to fit any particular genre — some suggest a “rock-band” approach to realization, while others work best in more abstract arrangements.

The follow up to Mountain was a release called Forbidden Planet which was released initially very quietly on cassette by Brave Mysteries. That release was highly textural and an exploration of drone and soundscapes that focused primarily on guitar. Listening to it on tape adds an extra layer of hiss and noise. Do you see that record as lending itself specifically to the format of cassette?

I did, after it was finished. Listening back to Forbidden Planet is a challenge because there are so few concessions to listenability on that one. Like many harsh noise records, it’s to be endured — maybe even “beaten” — so that completion is an accomplishment. Records like that seem to benefit from an explicit layer of physicality between the listener and the sounds themselves. Cassettes provide that sense of confrontation: they are physical things that the listener must wrestle with, unlock. As you suggest, there’s a layer of hiss that won’t allow you to forget there’s a machine whirring away behind the music. Tape gets tangled in players, sometimes it tears. Cassettes demand a certain level of physical interaction that you don’t get from the digital medium.

Still, I don’t like obscurity for the sake of obscurity. I’m happy to reissue cassette releases in more accessible and widely-distributed formats, should the opportunity arise. The listener can choose which format is right for him or her.

Rest of the interview after the jump…

Photo Markus Schaffer

You’ve signed with Relapse records, who immediately reissued Invisible Mountain on cd and packaged your first album, Impale Golden Horn, and the aforementioned Forbidden Planet, on a 2 cd package. Were you label shopping at the time or did they approach you? They’re clearly enthusiastic about Horseback to rerelease a cd and a double cd of “old” material.

No, I wasn’t shopping for a label at the time. I got a message from Matt Jacobson out of the blue, asking if I’d be interested in doing a record for Relapse. Relapse’s involvement brought Horseback’s music to a larger audience almost overnight.

Whose idea was The Gorgon Tongue (the 2cd set that combined Impale and Planet)? Is there something connecting two releases to where you felt it appropriate to have them combined together? Forbidden Planet feels like a much darker Impale Golden Horn.

This reissue comp was my idea. I suggested it to Relapse because Half Blood was taking longer than I had anticipated — the reissue bought me more time to finish the new record! And yes, I think the two records on The Gorgon Tongue complement each other well: They’re both examples of the more abstract/psychedelic side of the project. Denis’ cover artwork, featuring Pegasus being birthed from Medusa’s severed neck, unlocks the tension created by pairing the two records: sublime beauty and metaphysical terror in equal measure.

Your friends and collaborators Locrian have also just signed with Relapse. Do you see the label as trying to carve a niche of challenging and experimental artists such as yourselves?

Is that what Relapse is up to? Haha … I don’t know. In the mid-2000’s, Relapse became associated with grindcore and tech-death almost exclusively, but that’s not the Relapse I grew up with. I associate them with experimental and atmospheric heavy records (like dISEMBOWELMENT’s trailblazing record Transcendence into the Peripheral and even Onward to Golgotha, which remains entirely unique — even in Incantation’s own catalog — due to its atmospheric qualities) along with the high-BPM “brutal” stuff. And Relapse is certainly not new to the noise genre … they were releasing Merzbow records in the mid-90’s, after all. They’ve always been an incredibly diverse label, so I feel they carved their niche long ago.

Has there been any talk of releasing your collaboration on cd?

I can’t comment on a reissue of New Dominions at the moment, other than to say that I’d like it to happen.

The label is clearly ok with you working with other labels, as you’ve released material under Hydra Head, Utech, and Brutal Panda since signing. How important is it important to you to still work with these smaller labels on more “specialty” projects?

I like to maintain the relationships I’ve built with all these labels. For me, one of the biggest rewards in making music is the sense of creative community it inspires. Artists, engineers, and labels come together with music listeners to make all this happen at the cultural level. I try to stay involved however I can. For better or worse, music is my life. All the other individuals engaged in similar creative work feel like an extended family.

All of your releases have a very different sound and quality to them, and there are a number of different Horseback releases in the world right now. Some songs are more black metal, some more drone, some more rock. Do you get into a certain headspace to record a song for a split or 7 inch, or do you just record all the time and portion out material accordingly?

I record all the time. Every day, if my schedule allows it. Eventually, certain groups of songs seem to indicate that they’re ready to come together as a cohesive record. Sometimes the common thread is a sound, a mood, a technical approach, a thematic narrative.

I also spend a lot of time listening to a wide variety of music. This helps me evolve my understanding of what music is, what it means to make music in the first place. I’m always learning; the ground’s always shifting under me. I try to stay on my toes.

Is it important for Horseback to experiment with different modes of writing before locking into writing an album?

As far as I’m concerned, experimentation is an essential aspect of any vital creative process. I’m always experimenting with new approaches to composition and recording. For me, this project is partly about that process — finding new ways to construct a song.

You mentioned in an interview, I believe it was here on CVLT Nation, that you discovered your ability for “harsh vocals” during the recording of Invisible Mountain. I imagine that was an exciting moment and quite a breakthrough in the writing process. I’m curious, what was the impetus to attempt this style of vocal? What was it about the music or the mood of that album that called for vocals like that?

I like “harsh vocals” (kind of a misnomer, I think, because this vocal style doesn’t really sound so harsh once you’re accustomed to it) because they add a level of abstraction to a composition. All singing is an affectation of the human voice and is therefore somewhat abstract. By removing most sense of melody, a harsh vocal style goes a step further in emphasizing the voice’s textural qualities.

In almost every case, melodic vocals dictate the way we hear a musical arrangement. The voice is the most immediately relatable element in a recording, and if it’s present, other compositional elements exist to support the vocal melody, to provide variations on that melody, or to counter it somehow. Often, this is exactly what you want. In Mount Moriah, for example, we concentrate on making space for Heather’s vocals to sit front and center. They are meant to be the centerpiece of those songs.

But there are times when melodic vocals would get in the way. If you want the listener’s attention to be distributed among the other elements in a recording — which is what I’m often shooting for in Horseback — you can remove that central, highly-relatable vocal melody to achieve a more balanced “sonic ecosystem.” (Of course, there can be additional layers to a harsh vocal performance. Some vocalists want their voice to sound evil or deranged or something like that. I don’t mean to suggest that this isn’t often the goal for harsh vocalists.)

All this feels somewhat awkward to try to explain, but I haven’t found a better way to articulate the way I hear this stuff. I don’t hear harsh vocals the same way I did when I started listening to metal and power electronics back in the day … I’d be lying if I said I wanted my voice to sound “brutal.” These days I’m just as enamored of David Tibet’s vocal delivery as I am of Nocturno Culto’s. It’s not as much about the brutality as it is about the otherness.

The distance between Impale Golden Horn and The Invisible Mountain isn’t really all that great. The textures are different, but the compositional approach is largely the same. The intended effect is the same. Invisible Mountain’s mood is darker. I hadn’t attempted harsh vocals before recording that record; they were an experiment to see if I could include vocals without compromising that sense of abstraction — that otherworldly sonic ecosystem I’m talking about. If harsh vocals hadn’t worked, I probably would’ve kept the record instrumental for the most part. So yes, I was glad they worked out. And you’re right, it was a major breakthrough for me! Developing that vocal style has opened up other possibilities.

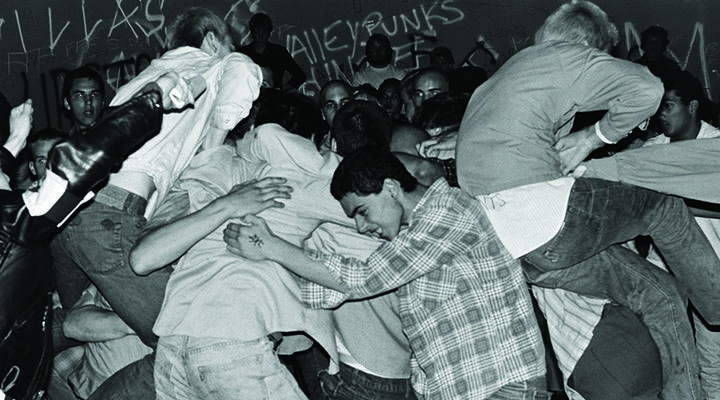

Photo Rich Trash

Horseback has always been your project, though you do call on guest musicians from time to time. The promotional photo for Half Blood features you and a full band. Is this just the live band, or did everyone pictured make an appearance on this new album?

That’s the current live band, but those guys often appear on the records these days, too. It depends on the record, and the song, really. From left to right, the photo you’re referring to is me, Rich James (guitar, of the Durham band Hog), John Crouch (drums, of the Chapel Hill band Caltrop), and Nick Petersen (bass, of the Chapel Hill/Raleigh band Monsonia). These guys are all friends who have been active in bands around here for a long time.

John played drums on both Invisible Mountain and Half Blood. I’m not exaggerating when I say that he’s one of the best drummers alive. The first three tracks on Invisible Mountain were recorded the first time I played those riffs for him, with the tape rolling (basic tracking was just the two of us on bass and drums). John’s that good at what he does. Sometimes songs have more energy if you record them without rehearsing them to death first — I remember reading an interview with Michael Gira where he said the point of practice was to try to get back to that initial moment of inspiration you feel when you first write a song.

Nick runs a recording studio called Track and Field here in Chapel Hill, which is where we do most of our drum tracking. We tracked drums for Invisible Mountain and Half Blood at his studio in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Rich joined the lineup after we had done the initial tracking for Half Blood (almost two years ago now), but he’ll be on some stuff in the future.

Some Horseback songs feature programmed drums. Is this out or convenience or inability to find a human to perform these parts? Or is it just the aesthetic of the drum machine/programmed drums itself?

It’s all of those things. Sometimes it’s the right vehicle for a composition to get where it needs to go. It’s also an economical solution if you don’t have funding to record in a studio.

The Chateau is your home studio, correct? Can you provide some insight as to the setup you have there? Do you record analog, digital or both?

Yep. It’s a very modest studio, a bedroom-studio kind of situation. I don’t think it would work for what I’m doing if I didn’t have a lot of experience making records already. There was a lot of trial-and-error involved in my early days as an engineer … Hell, there’s still a lot of trial-and-error. I frequently use Nick’s studio down the road for drum sounds — Nick’s a wiz at that sort of thing. Recording and editing is usually digital, though I’ll use a 4-track if I want something to sound more lo-fi. I do most of my mixing through headphones because I don’t have a very good room for it.

Are you just as interested in recording as well as playing, or do you see it as more of a necessity than a passion?

I’m definitely interested in recording as well as playing. Recording is a part of the composition process for me — the studio, even a very modest one, is an instrument every bit as essential as the guitar. Since I’m recording nearly every day, songs often go through wildly different stages before they’re finished.

I occasionally produce records for other bands, but I don’t get a chance to do this as often as I’d like. The most recent record I did with a band I’m not actually in was with a swamp-rock band called The Moaners.

I’m not as obsessed with recording as I used to be. When I was first developing my chops as an engineer, I subscribed to Tape-Op, stayed on top of the latest gear, actively researched all that stuff. Now I just research specific questions as they arise. I still love it, though.

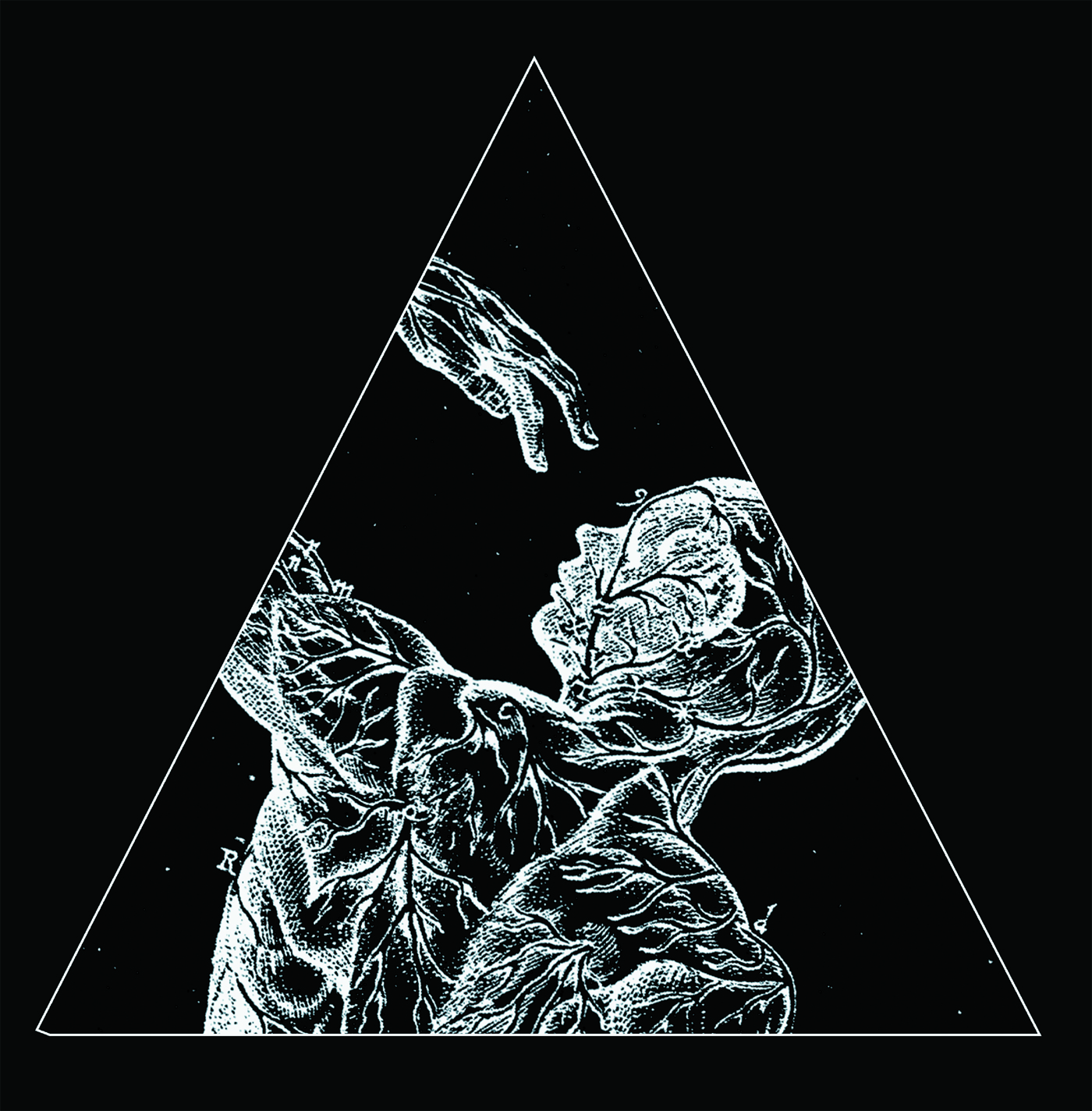

The visual side of Horseback is equally as important as the aural side, and you’ve been very fortunate to have a partnership with Russian Symbolist painter Denis Forkas Kostromitin who is simply an incredible artist. He seems to be the perfect visual interpreter for your music and he creates environments as dense and beautiful as the music. How did you come into contact with him? Was he doing much album artwork at the time?

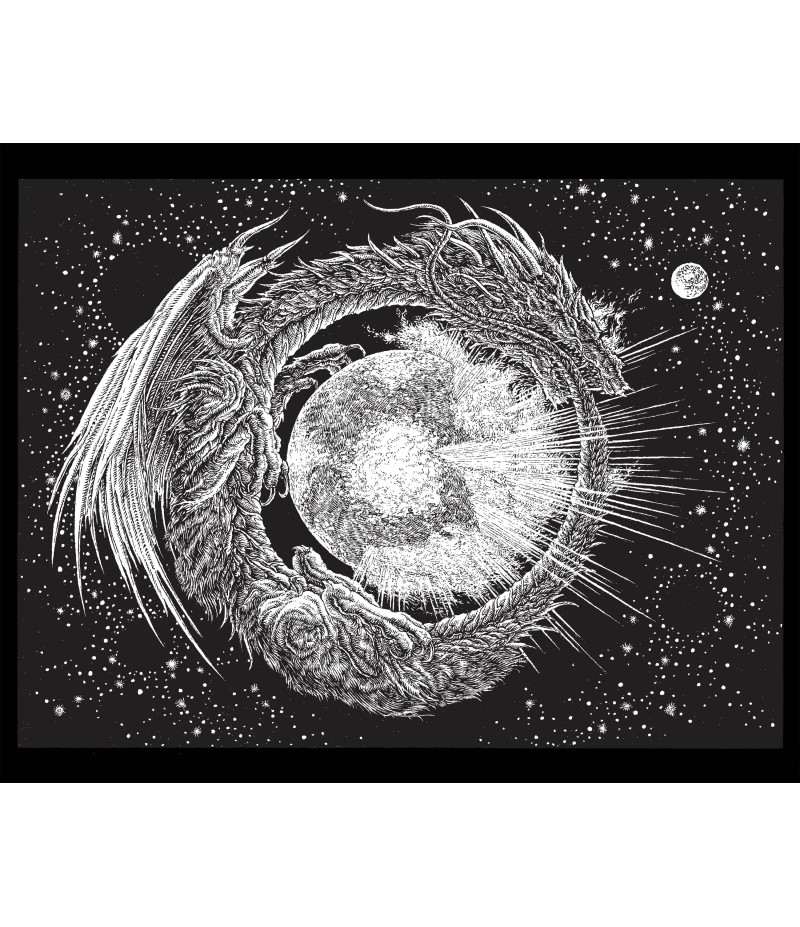

Keith Utech of Utech Records introduced us in 2009. Keith had previously commissioned Denis’ drawing, The Moment of Truth, for a different record but it didn’t work out. The image worked perfectly with The Invisible Mountain — it had the feral violence I wanted, the sense of dread … even the cyclical motion of the beasts in the drawing evoked the cyclical riffing on the record. In fact, by either coincidence or synchronicity, the scene Denis depicted was described in the lyrics to the first track, “Invokation.” It was uncanny — a magical pairing, to be sure.

I think The Invisible Mountain may have been the first album released with Denis’ artwork. I know he’s done a few more commissions since then, apart from his work with Horseback.

How closely do the two of you work together on a project? Do you already have ideas in mind that you communicate to him, or do you give him the music and let him draw his own conclusions? Obviously the Gorgon Tongue release landed itself to specific visuals.

We work together very closely, for the most part. We didn’t get to communicate about The Invisible Mountain, of course, but we have been able to for every other record.

When Horseback and Locrian recorded New Dominions, Terence had recently read Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us, and the lyrics Terence and I wrote were based in an appropriate kind of apocalyptic naturalism. Denis read Weisman’s book and filtered its themes through his own historical research (in this case, architecture specific to ancient Russian churches) to arrive at his cover image, The Wooden Word.

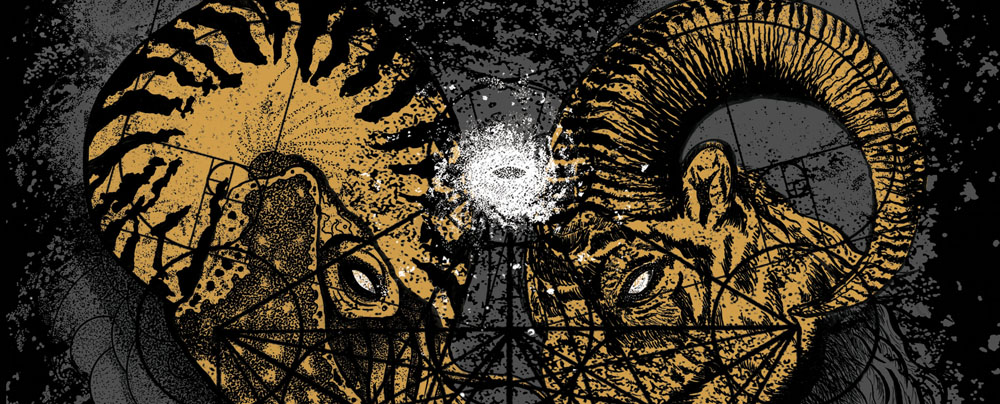

Once the thematic layer of Half Blood — hybridity, alchemical transformation, evolution, etc — became clear (this usually happens in the middle of the recording process), I contacted Denis and described these themes to him as they related to the sounds I was exploring. He suggested the tauroctony might serve as an appropriate foundational symbol, since in the Mithraic Mysteries this symbol represents a kind of life-perpetuating sacrifice. (Often Denis’ own occult studies suggest new ways for me to think about a record’s concept … This was true of the Gorgon Tongue reissue, as well.)

What can you tell us about the cover artwork for Half Blood? How directly does it tie in to the concepts of the record?

After Denis suggested the tauroctony, he sketched a couple drafts. Originally, he included Mithras’ hands, in deference to the original frescoes. However, I wanted to avoid the duality implied by two opposing characters, so Denis adapted his image by removing Mithras entirely. This allowed the agency involved in the transformation process to become embodied in a single symbol, rather than in the friction between two separate entities (ie, Mithras and the bull). Because alchemy is concerned with internal/personal transformation, this seemed more appropriate. Once all this was in motion, I was also able to incorporate some elements of Zoroastrian mythology into the lyrics I was writing for this record.

Denis has written an article about his process in creating the cover image, so I don’t want to talk too much about that process here. I’d provide a link but his article hasn’t been published yet.

Forkas has worked with you on three albums and the Locrian collaboration with other artists handling your various other releases. You hand drew the artwork for the Forbidden Planet cassette. What is your background as a visual artist? Do you think you will ever generate artwork for one of your releases in the future?

I’ve been drawing all my life. When I was very young, my mom used to take my sister and me to make charcoal drawings of landscapes and architecture. I fell in love with drawing long before I fell in love with music. Over time, I grew to love writing and recording music so much that it consumed me. I never really had all-consuming experience with visual art, so it remains more of a hobby. There are moments when I feel inspired, but I never developed any sort of expertise with visual art so those moments of inspiration can end in frustration.

A couple years ago, I did a series of collaborative ink-and-watercolor pieces with Matthew Bower and Samantha Davies of Skullflower/Voltigeurs. This was especially fun because it involved sending unfinished art back and forth across the Atlantic. It was a slow and dirty process — none of that photoshop shit! Haha. We had originally planned to use those pieces for the Voltigeurs/Horseback split Turgid Animal released in 2010, but Matthew came across a different illustration he wanted to use instead. They’ll be used for a release sooner or later, I’m sure.

Most recently, I drew a cover for a four-way split cassette that will be released on Handmade Birds this year.

I do enjoy making art for records, but collaborating with another visual artist can be more rewarding. The full-lengths, especially, begin to feel very claustrophobic after a while. It’s hard for me to maintain perspective when I’m writing, performing, recording and mixing a huge portion of each record — I tend to become obsessed with every detail of the recording and I lose myself in shadows. Bringing another voice into the process can open it back up, shed a bit of light on the final steps so that a record isn’t quite so exclusively/anxiously/obnoxiously a reflection of myself.

Stay tuned for part two of CVLT Nation’s interview with Jenks Miller.

New Comments