How and why did Dreadlords first come about?

B: I first began writing songs for Dreadlords after a couple years of immense frustration, living in Baltimore in places with no heat that were former servants’ quarters, seeing people get shot on the street, working in partially abandoned buildings, sleeping in places that were a step away from anarchist squats, being morosely misanthropic, walking streets at night alongside junkies and trans street walkers, a step away from zombies, etc. At the time, society appeared absolutely doomed. Old Delta Blues spoke to me then, and very specific kinds; nothing with piano, because it’s too bright; nothing with drums, because it’s too rhythmic; no electric guitar, because it’s too bombastic; nothing female-fronted, as the vocals are too high; I only wanted to hear defeated old men in front of a lonely acoustic guitar, because that reflected my future. I began collecting mechanical, non-electrical, crank-controlled gramophone players and dust-covered shellac 78s to explore this new dimension. I started writing songs with that old aesthetic in mind and since I was in a black metal outfit, everything sounded vaguely like Inquisition. I showed my demo sketches to T.O.M.B., and the rest of the band surprisingly didn’t think it was crap. They in turn showed me things like King Dude, Wardruna and Type O Negative – it all fit. Our black metal instincts as a band gradually made me compromise and leave my acoustic guitar in favor of a banjo with a pickup, but a little blues metal monster was formed in the process.

Dreadlords have a very specific and fully formed aesthetic: lyrically and musically, there’s a strong Southern American flavour with the folk and blues traditions, the religious imagery, the rural instrumentation, etc. Where have these influences come from? Have religion and/or Southern culture and traditions played a big role in your life, and if not what has drawn you to them artistically?

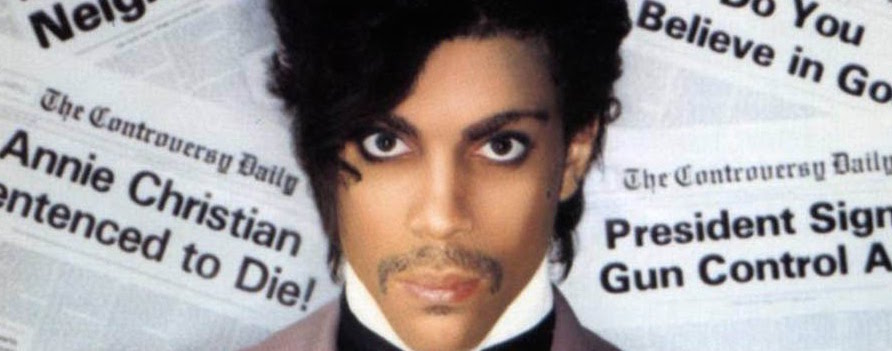

B: Probably our biggest influence from Southern culture comes from Robert Johnson. I personally view him as the major reason why there’s even any rock and roll and heavy metal in the form we know it today. For those who are unfamiliar, Robert Johnson was a blues performer partially famous for a nefarious rumor he spread. He claimed he sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads at night in exchange for learning how to play guitar – and to get famous doing so. Such a claim wasn’t novel at the time. There was a least one other blues musician, Peetie Wheatshaw, who basically said the same thing. Anyway, Robert Johnson is the one everyone remembered and most likely because he was poisoned at that grand age of 27 – something those with more superstitious inclinations in the 1930s viewed as the devil getting his due.

I was born and raised in Kentucky and it was certainly bleak enough to provide the fodder for a lifetime of music. To start, many of the males in my family are Freemasons – my father has the distinction of being a member of the Knights Templar wing of the fraternal organization. My father also was a Luddite when I was a kid, so I wasn’t allowed to watch TV, play video games, or do any of the other mundane tasks modern children love. On top of that, it was great fun to see the sky turn green every couple of months right before a tornado came and you had to huddle in your cockroach-infested and flooded basement near a foundation pole.

Much of the religion in the South was a great source of frustration, too. Many people in my town vocally commented on how all of the rock bands I liked on the radio in my mom’s car were Satanic. Much of the religious and the political mixed down there. The father of a friend of mine would constantly listen to the KKK Grand Dragon on the radio while sitting next to his oversized copy of Mein Kampf. We’d even go to demolition derbies and shoot guns in Fort Knox. If our music seems to breed lyrics about degenerates and murder ballads, it’s because they come from a very real place. I’m at the tip of the iceberg here when it comes to my crazy stories about the South.

S: Also growing up in the South, and being quite distant from society, I saw the tyrannical force of Christianity and it’s various sects that were more rooted in southern culture. I saw through the lies at an early age. I was seen as the dark one… the one that led others away from the savior, the ‘witch’ who didn’t go to church and worshiped the Devil… all of this before I even hit adulthood. I grew up smothered in Catholicism, though I deeply resented every part of it. Whenever I was dragged to church, I took part in nothing. I would look around at the herd of sheep that had gathered and thought about how much I despised each of them for no reason. I’d scold my parents for putting money in the basket because I felt the church had no right to it. I would watch the priest and wonder why he would agree to not partake in sexual activities and thought about how sinful he probably really was (I knew a lot of depraved things as a child).

My great uncle was a priest, so I got to see some “behind the scenes” business and was frequently gifted change from the “please give us your money, we swear it’s going to a good place” basket. Not once in my time knowing this man did I speak to him; he swore I was a mute. By the age of 12, I convinced my parents that church was pointless and we no longer went. I could go on, but I think my “devil child” point has been made. The blasphemy was always there. I suppose you could say I was truly born into the arms of the devil.

[ot-video][/ot-video]

Musically and lyrically, Dreadlords seem to draw most heavily from the apparently disparate traditions of American folk and blues and Scandinavian black metal. Where did the idea to combine these two styles come from and why the attraction to them?

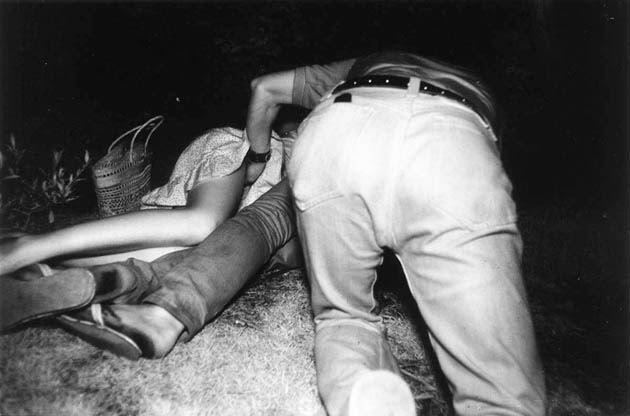

B: Years ago, at a time of great personal difficulty while living in Baltimore, old Southern and black blues struck a powerful chord in me. It seemed so much more evil and experimental to just sit on a stool, play acoustic guitar and spill your meditations and obsessions over the darker side of life. There’s a legend that Robert Johnson would record facing the wall of a studio or perform live staring wildly at the eyes of one, and only one, female in the audience – the old blues gods never give a whit about much. Hell, they were even trainhoppers and functional alcoholics.

Sonically, the music made before the common availability of electric instruments sounds otherworldly – like the transmission of a ghost. There’s something about a crackling, detuned and dying gramophone record that’s far creepier than any black metal band. Before forming Dreadlords, I’d played for years in noise bands and the noise, black metal hybrid that is T.O.M.B. too. I love black metal and it’s played an integral role in my life. However, I think its spirit, so to speak, lies in a much older American tradition.

Your other project T.O.M.B. is known for its ritualistic recording practices: recording in different environments and locations with significant meaning attached to them, using various found objects for instrumentation, etc. Do you employ similar methods with Dreadlords? What is the Dreadlords recording process like?

B: When T.O.M.B. got into gear, getting tons of field recordings, it really felt for a second like we were creating a new subculture or way of life. Our second home was whatever massive abandoned structure we’d get lost in for hours that weekend. None of us have stopped the whole urban exploring thing; it’s a part of who we are now. Samantha spends most of her time in untamed and primal forested areas, giving way for ancient energies that can be felt in the core of our music. Some of the songs on Death Angel were partially written and demo recorded in cemeteries at night, tunnels, and in the tresses of abandoned bridges. These environments have a very strange connection to the blues. One reason why superstitious people in the South believed Robert Johnson had sold his soul to the devil is because he disappeared for a short spell and returned with an uncanny ability to play guitar. Music historians have recently discovered that during this time, he stayed with one Ike Zimmerman, and the two practiced guitar constantly at night in a cemetery. Appropriately, there are no existent recordings of Ike Zimmerman. When I first started listening to black metal in high school, I was already doing the cliché, hanging out in cemeteries at night. It seems like a natural connection to me.

S: Dreadlords is truly as ritualistic as T.O.M.B., but the magick remains brewing in the background as the main supporting force.

[ot-video][/ot-video]

Dreadlords’ music features a lot of esoteric instrumentation – bone chimes, occult bells, singing bowls – could you talk a little about this? Who plays them/how you came across them?

B: Part of what we do is connected to ritual magic and anything Luddite. For a while, I had an intense interest in gramophones that led to the creation of a project called T.A.Z. where I’d release lock grooves on recycled acetate records – distributed through a mail-only label of course – or we’d play live without amps, a PA, or anything plugged into an electrical current. On the other hand, there’s Bride, our project exploring Solomonic ceremonial magic and Skulsyr involved with Seidhr. The instruments in these experiments bled over into Dreadlords’ songwriting. Death Angel features bone chimes, antique violins, tribal drums from Africa, old ritual bells from India, a singing bowl repurposed for use in The Lesser Key of Solomon, and there’s our beloved banjo, of course. The song we did for your CVLT Nation comp has a music box and gramophone player too.

What has the response to Dreadlords been like? Do you play to the same audiences as your other projects?

B: I imagined Dreadlords would be nothing more than, at best, a nice idea to be ignored on some tape comp. The response to our music has fortunately been overwhelmingly positive. There’s a bubbling new style of bands turning to old sounds and making them their own. I’d uncomfortably lump Chelsea Wolfe, Bain Wolfkind, King Dude, Noctunal Poisoning and Panopticon into this primordial genre. They’re all getting a lot of attention too. I suppose the recent resurgence of neo-folk hasn’t hurt – maybe folk and electro-swing as well.

We have played to a nice crossover of audiences. It’s cosmopolitan to see some industrial producer, a guy covered in Watain patches, and a scummy looking noise kid in your audience.

S: Many of those who approach me after a show realize that Dreadlords isn’t just music. The songs aren’t simply chords, lyrics and a drum beat. There is always something more to it, something dark and spiritual. It could be the incense I burn, the singing bowl which can send you into a trance, or just the strong presence of what truly lies beneath our music.

Follow Dreadlords on Facebook

![dread]10410733_603474619757916_1523532471288373016_n](http://staging.cvltnation.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/dread10410733_603474619757916_1523532471288373016_n-700x385.jpg)

New Comments