A few of your pieces seem to focus on the urban environment and condition. Good Day to Die, Terminal Waves Brown Sky in particular grabbed my eye when looking over your stuff. Being based in New York City, has this sprawl of concrete and asphalt shaped your mindset to a degree – maybe in terms of how you see the world now after all these years?

Carl: It definitely has and I don’t quite fully understand how. It’s more of an internal thing that happens. The paintings I do are very much about a place, but maybe more about conditions of living. The light of the east coast has dramatically changed things. Good Day to Die is the closet thing I’ve done to a large-scale landscape painting at face value, so to speak. Personal issues are veiled, coded within the painted image, usually not emphatic. I was just responding to this ocean of newly experienced color/light and this ocean of concrete, looking out a window in Washington Heights at that scene. “Good Day to Die” refers to fearlessness in embracing life and change. Themes of mortality were going through my mind when I first moved here. Contemplating death’s realities, being in this ocean of humanity that is New York City, something about that scene really resonated with me. Those colors, of the natural light in the photograph, are reported be experienced after death in the Bardo Thodol (the painting’s subtitle). I’ve seen that combination in dreams. Gerhard Richter said something to the effect that “You take pictures to take a picture. You’re lucky if one will become a painting.” That became a lucky one. I’m often revisiting photographs in painting.

In regards to my last question, over the years, you’ve also lived in Memphis and Oakland. Between these cities, NYC included, they all compose a pretty specific regional culture and different taste of the American Experience. Was there one location that might have stuck out as place that really lent a role in inspiring and forging a style for you?

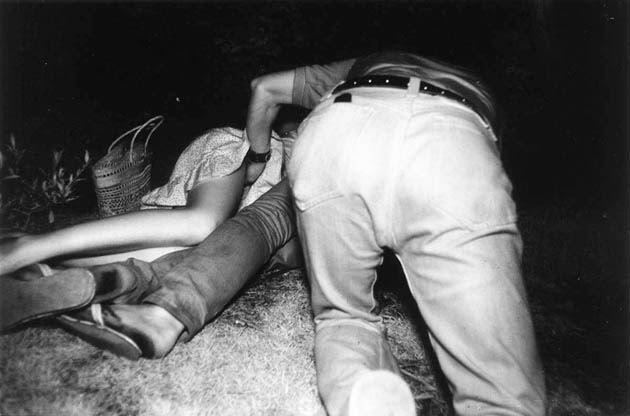

Carl: Memphis inspired images, artwork forged via Oakland. I considered painting images from Memphis, wondering what it would be like to reconnect through painting, to somewhere I could no longer identify with, yet had a huge influence, shaped and formed identity. In Oakland, I was painting a lot from direct observation; responding to ‘what’s around,’ practice rooms and streets/neighborhoods. I got inspired to use photographic/film still sources of Memphis after seeing these tense black and white films my friend Brent Shrewsbury had made. Witnessing this familiar, sad, haunted place in 16:9 ratio, this was an entry point into representing Memphis, through artworks.

I realized over and over that there’s a sense of estrangement that is one of the louder themes in my work. A viewer may not read that, but for me it’s there. It’s a search for home and I might not get there honestly. A friend with a gallery in Detroit recently invited me to do an exhibit, with work that’s all Detroit-themed. I was actually born there, my Mom and Dad were from there, there’s a fleeting but strong connection despite the separation. I’ve been archiving childhood photos of my Mom, some have indicators of time and place, like old cars. I’m now just investigating these photos, wondering how to respond through painting.

Most people hear about Memphis and think of Elvis or Gangster Rap. But there was also once a strong, rich undercurrent there for a short period. Memphis had one of the strongest – and definitely the most unusual – punk scenes ever. There was a certain character to it that I’ve never felt anywhere else. I wanted to insert that character through painting, even felt a responsibility in giving a visual representation to the place. Another aspect is that I came from was a scene that was musical and not visual. Well, visual in a sense that there was the homogeneous Black and White photocopy image, which was great. You’re trying to negate something, not archive or document it, working to destroy, to tear down all the lameness around you and create something new. It’s a frustrating yet interesting thing reconciling painting and Punk/Hardcore musicianship. Painting is such an old tradition and craft. Punk Rock is always re-inventing itself. So between those two things I just wanted to create something. I feel very lucky to have created music with the small group of friends that were trying to change the world through sound. A painting will never do that.

Banana Rats, a piece you did back in 2006, has this almost totalitarian feel to it. Combat boots with the pants tucked in. A hallway stretch’s out behind the unseen faces of the duo. Upon a little research, I came upon a species of rats that reside in Cuba that are known as Hutias. Which are, most likely not lovingly refereed to as “Banana Rats” by those soldiers stationed there. It sorta of clicked at this point, in terms of what I was staring at in your painting, that it was was Guantanamo Bay. Outside of the political and moral debate regarding Guantanamo, was there maybe something else that spoke to you about this piece and situation?

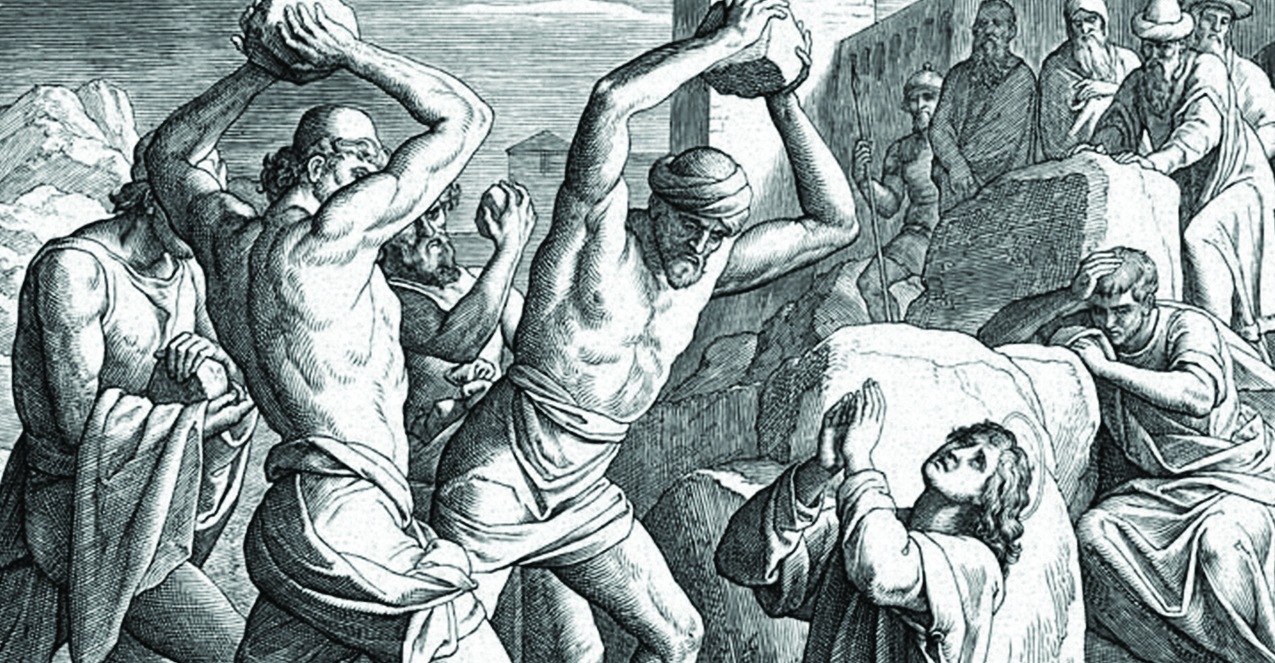

Carl: Somebody that’s made to feel less than an animal, something about it just resonated. I connected to feeling that way in a systematic sense. Just the anger. As an artist you’re somewhat responsible for addressing issues of your time. Painting owes that to the world. I had read a few pieces about that situation and it just really moved me. As a musician you can play benefit shows, which His Hero Is Gone and Drain The Sky did for Amnesty International a few times. I wanted that article’s text to co-mingle with the image in a way that you might not necessarily be able to read. In the drawing version, image and text veil each other. But that text, when you discover it has some clarity, lets that veil be removed and explains the situation. I try not to be political in my work, but there’s this contradiction which I respect. I feel like that act of painting isn’t political. It’s something else. Struggling to find a voice within the paint and material. A little more introspective, the deeper concerns that come out. In that painting, I’m dealing with issues of being from a low socioeconomic background. It’s visceral. I do feel one day that I’ll make severe political paintings, the time just hasn’t arrived.

Back in 2005, you created four graphite on paper pieces entitled “Erased.” The first one features a rather ominous structure, what looks to be a burnt out or heavily damaged project housing unit, while the last piece is the mugshot of an unknown person. When all four pieces are viewed in succession, its almost as if the building and text slowly melts away into the mugshot. Correct if I am wrong here, but the mugshot bears a striking resemblance to you back in the day. If I’m wrong on that guess, was there a person or news article that spoke to you in order to usher in these four drawings?

Carl: Ha, yeah that’s not me. It’s Chuck Thibault, my friend and band mate (singer) from Man With Gun Lives Here. Those works are definitely made to be viewed together. The building is the Baptist Hospital, in Memphis, symbolically a very proper representation of that place. Absolute impoverishment. If you were a poor person with problems, you’d wind up in a hospital like this, become lost in the system, your life at risk for lack of care or mis-diagnosis. There were a lot of crazy people (for lack of a better PC term) walking around in Memphis with nowhere to go. Thrown into places like this, jailed, medicated and later kicked out onto the street. Hospitals there feel like places designed to keep you down, a brutal, systematic way of keeping you in your place. That building had this beautiful, brutal architecture, and I wanted to commit to making large-scale oil paintings of it. The series of drawings, the erasure on them; the motion of erasing and wiping away your existence. That’s the whole idea- Shut up, acquiesce, you’re worthless, now you’re gone. There’s no trace of you left. There are a lot of urban myths and legends there. A friend of mine, Matt Brown (RIP) once told me he’d talked to a gang member and a cautionary tale of sorts that came up, some people actually believe that in the Memphis prison system, rival gang members are killed, somehow erased from existence, turned into prison food. In Memphis, there’s this sense of magical realism, the fantastic, the unbelievable and the real coinciding. There’s a dark magic at work there. You become very much a believer in superstition; legends and myths are prominent. It’s almost proper to believe that it’s true and accept it as real. Weird things happen all the time there. So yeah, killed and Erased.

The texts on one of those drawings, and on some of the paintings, are referenced from notes a lady had scrawled in crayon and duct taped to telephone poles. It was once between His Hero Is Gone tours, I felt sometimes that I saw her more than my friends. It definitely impacted me, being around people from half-way houses and mental institutions, seeing them dig through the trash for food. This lady, her notes started falling off the telephone poles into the water that had gathered on the street. I rescued a couple of them, so many, all of which had the same bizarre messages written on them. Many years later, I felt like giving her and her notes a voice. Those notes and the Hospital, the question and its answer, a perfect representation of Memphis, to me.

Obviously, the piece entitled 15 counts of arson was going to come up. Anyone familiar with your previous work musically in His Hero Is Gone can immediately identify that piece. 21 years have passed since you created that, but honestly, it seems to have so much more to say now, what with the economic and cultural divide we have here in the United States. The gas station tinged with fire, the masked revolutionary with a bullet belt slung over his shoulder. Looking back at it from my perspective, it’s almost like an omen of what was to come in terms of social change. What influenced you most about that piece?

Carl: A photograph I took inspired it, the idea of struggle and adversity, a connection to people’s liberation struggles worldwide. I knew that this company was enslaving and killing people basically for gas and profits, on the other side of the world. I simply noticed the ‘H’ missing from this gas station’s sign, while passing by one night after getting off work, and manually shot a 35 mm photograph of it, developed and printed it months later. The scene seemed to convey the thing calling attention to itself as a ‘sign of the times.’ I was becoming conscious of other indigenous peoples’ modern day struggles across the planet, relating through blood I guess, with ancestry in the Sioux uprising of 1862. There was no internet, I spent a lot of time at the public library. At the time, I knew little of the Ogoni tribe, corporate paramilitary forces, environmental racism, but when I passed by the scene, it invoked that awareness. I felt very disconnected from the rest of the world, being in Memphis. This was one way to connect, and convey I felt something in the world simmering, threatening to explode. I needed to convey imminent destruction, violence. Be it good or bad, depending on your point of view, somebody was going to put on a mask and bullet belt and be in this situation.

More so, looking back on it, what does it mean to you both as a person and as a artist?

Carl: I relate it to the band, mostly. My friend Dominic Gerszberg (RIP) saved the original watercolor painting. He saw the state of neglect that the painting had gone through. This painting survived years of my being away on tours, passed around in various places since I never had a stable home between touring. He saved it in archival materials, framed it with museum glass. I’ve never exhibited it, but it’s preserved and thanks to him, will be around for a while. I was just thinking about looking at it again. Its been covered, boxed up, for a long time. Just this week I had it out and I was about to unwrap it, but didn’t. That question has been with me a long time. Honestly, that’s too hard personally to answer.

Continuing on with the themes found in your work are the three paintings you labeled “Chernobyl.” The use of colors on these three pieces seems to directly represent the initial fall out and the eventual dying out of life. The house slowly melts away into colors as a result of radiation and a man-made catastrophe. In the last piece, transfixed in the center of it is a speaker, almost conjuring forth the image of sirens and warnings of this inevitable disaster. Even the reflection from the speaker’s dust cap speaks out, almost if we are looking back at ourselves. What drew you to the subject of Chernobyl?

Carl: Yet another photo that I saw and knew instantly that I had to paint it. Just addressing it as metaphor for personal catastrophe. It’s a place, an idea that represents those qualities, on a personal level. I also wanted to make a painting with a soundtrack, asking what a visual equivalent to a painting is. It’s an impossible question. There’s that contradiction of being from a background of punk music and trying to channel it into being a painter. I really liked how it all turned out, the acrid soundtrack, the palette and muted tones. I was just beginning to use that kinda voice in the paintings. In fact, I started washing things out even more in my work, draining happiness through color choice and strong hints of modernist painting style (referring to something that is behind the times, like Memphis), in the handling of the paint. And though it was inspired by and entitled “Chernobyl”, it also addresses the Memphis mental/spiritual battleground, and that theme of estrangement. Dominic, who I had mentioned earlier, was from Poland; I just remember him talking about witnessing the ashes falling down from the sky right after the Chernobyl disaster, as a child. I just immediately responded to the images, maybe in part to the stories he told me, definitely the barren, devastated mood they conjure.

At the end of the day when all is said and done, what’s the one piece that you’ve done that means the most to you? Perhaps even a turning point in how you saw yourself as an artist?

Carl: Definitely “Clear Channel.” I always like living with it. Everything I was trying to do as a painter coalesced in this painting, the image and the way its painted, the muted color palette choices, the limitations I placed on myself to impoverish the painting by depriving it of full color. Making it as barren as I could, but still letting the story and image come through. That proper balance I found in it. I really felt that I found that voice I was looking for.

Was it something that as you started creating the piece you felt it’s importance, or was it after finished and took a step back that it really sunk in?

Carl: I think both, actually. I knew where and when to stop, it happened very quickly over a couple of days. That was a rare moment of feeling success.

Abdulaziz Aleissa

October 1, 2015 at 7:47 am

Sean Brophy Yianni Tranxidis Sam Nevin

Monte Hamer

September 30, 2015 at 2:09 pm

This is so sick!!

Rich Evans

September 30, 2015 at 1:38 pm

Monte Hamer…HHIG!