Hey Ash, how are you doing? Congrats on your book release for KILL CITY, I’ve been looking forward to it for a while now! How did the idea for the book come about?

Hi, thanks! I’m great, thank you.

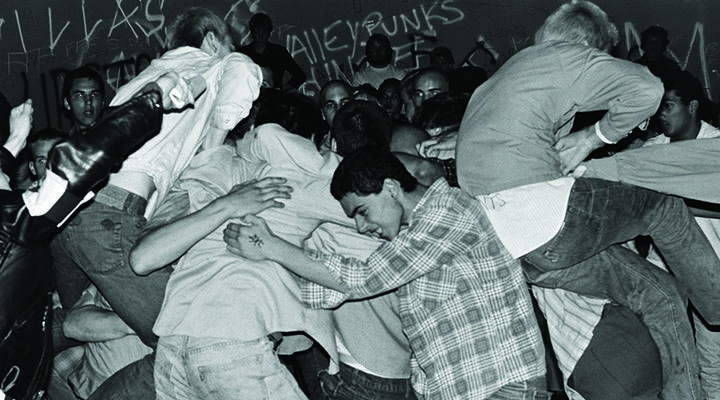

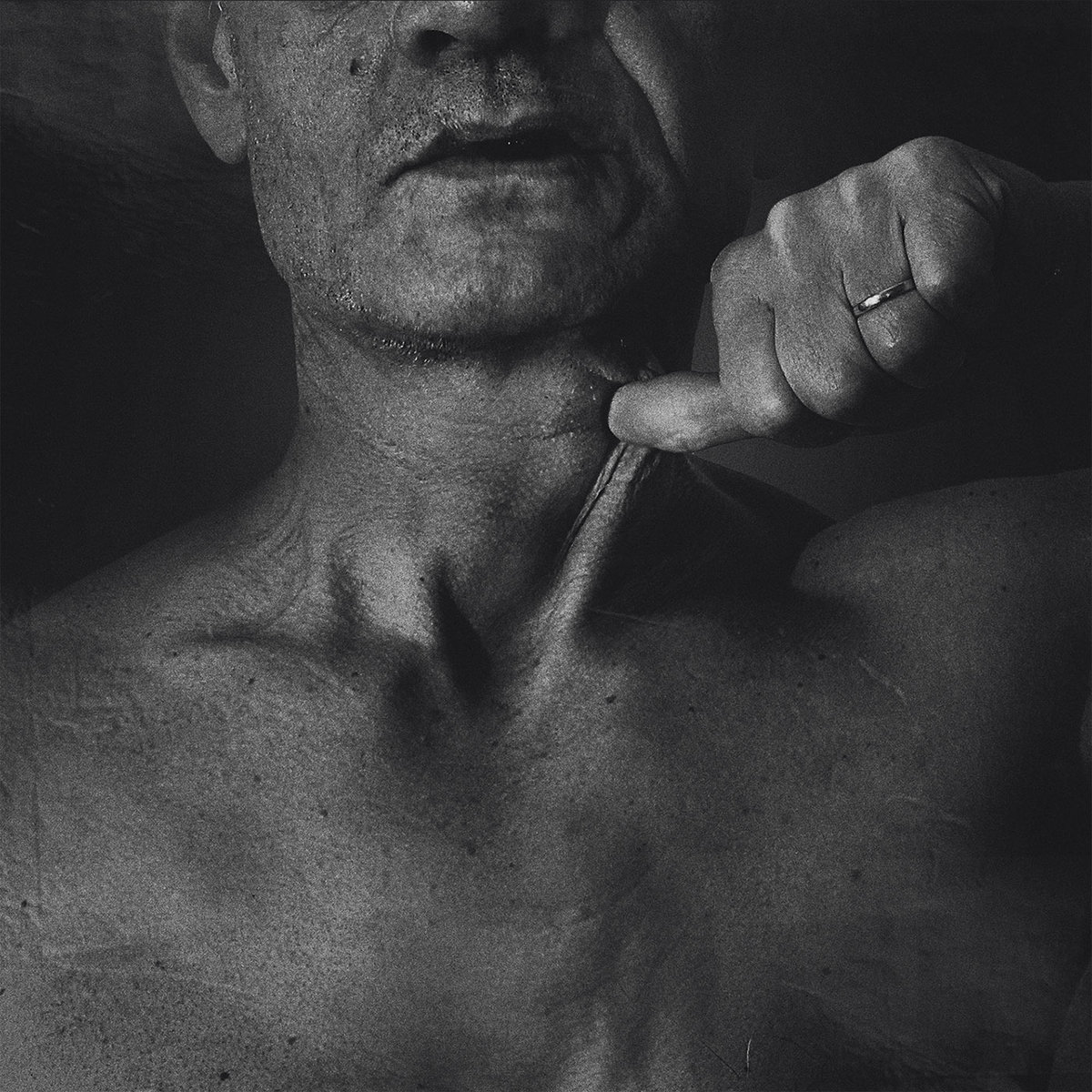

After creating such an extensive archive of work on this subject, it made sense to publish it as a book. Not only as an art book that is interesting to look at, but also with the purpose of bearing witness to this passionate movement from a perspective that was not being represented in the media. It was also meant as a gift to the community I was a part of, to show them how I saw them, and share with them these memories.

How did you come up with the name?

It was excruciatingly difficult to settle on a name! I turned to music, since it was such an important part of this culture and went through band after band, song after song, for inspiration. “Kill City” by Iggy Pop had the bite and irony I was looking for, and made reference to the city. Although the song addressed the overwhelming abundance of drugs in the city at the time and how it was killing people, I felt it also referred to the city government’s neglect of the homeless, the lower east side in general, and the brutal nature in which they treated squatters.

What drew you to the punk movement as a young girl? Did you face more discrimination for being a punk in Memphis than you did in New York?

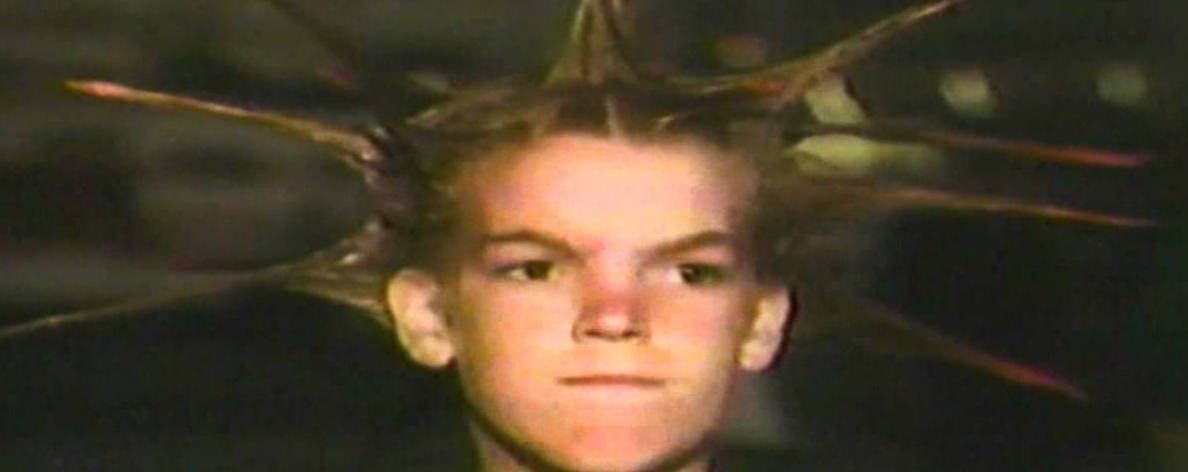

Really, just straight up rejection from mainstream kids – the cheerleaders, athletes, rich kids; even though I was athletic and made good grades, I was artistic and thought about the world in a different manner from them, which just wasn’t a good fit. I was anti-racist, hated being sexually objectified by men and cared about the environment at an early age, which didn’t go over well. I was a metal-head first, then in high school, I was introduced to punk music, and that was that. Yes, being a punk in Memphis in the late 80s/early 90s was much more uncommon than in NYC, so we definitely stood out and got harassed more.

Talk to us about how you ended living in a squat in NYC, and what made you decide to document LES squatters?

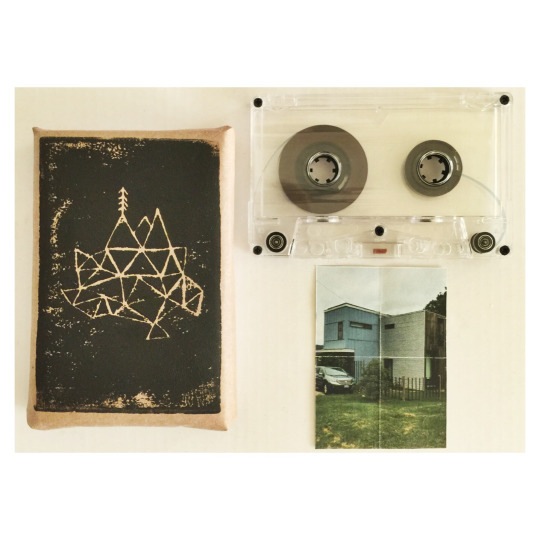

I basically didn’t have a place to live, couldn’t afford an apartment on my own, and some punk kids told me about squatting and invited me to come stay as a guest. Because I photographed my daily surroundings, it was a natural progression to do this in the squats. Also, squatters needed visual “evidence” to show how much time, money, and labor they put into the buildings for any future threat of eviction.

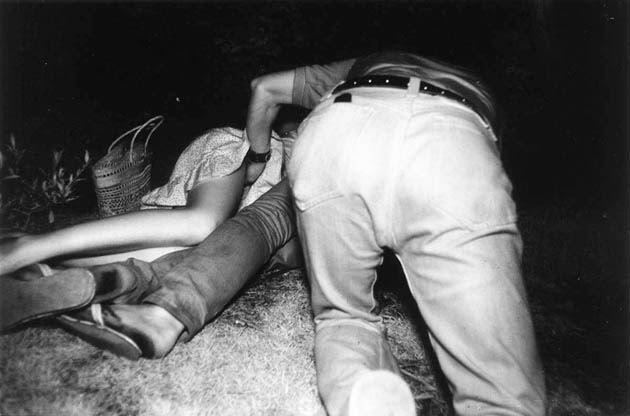

Do you feel that being a part of the squatter community gave you the opportunity to capture moments that an outsider wouldn’t have been able to?

Yes, it did, but I wasn’t thinking of it with that in perspective. I was just there, living life, and doing it. Taking pictures is what I did, so I did it there. No, most people wanting to take pictures were not allowed in, and in some squats, they’d be told to fuck off immediately.

How did squatting change your life?

I was about 18 at the time of being introduced to it, so I would say it helped mold my character. Those were formative years. I learned about being a part of a community and not necessarily putting my own needs first; thinking of the greater good. I learned construction skills, which was very empowering and esteem-building. I was free to dress and behave how I wanted, without a lot of expectations from others.

What was an average day like in Alphabet City back then? What did you do for work?

Wake up, drink coffee with friends, figure out our work day, do the work, get some beers, go to the park, roof, or community room and hang out. I had odd jobs – serving coffee, bicycle messenger, and I briefly worked for an all-woman’s moving company.

Are you still in touch with any of your housemates from back then?

Yes, I am in touch with almost everyone I have photographed, and I’m writing this from my friend’s apartment at See Skwat, where I’m staying while visiting. I’m looking out the window from the same view as 22 years ago, when I first came to this building.

When did you see the gentrification start happening to your neighborhood? Have you been back to the LES lately and seen how commercial it has gotten?

This neighborhood was already being bought up and developed when I was squatting here, but in the early 2000s is when you started seeing it look more like the west village – expensive cars parked on the street, trendy upscale restaurants owned by people who didn’t live in the neighborhood, or even New York. Family-owned businesses that had been there for decades were replaced by more upscale, expensive, corporate chain versions of the same thing. Along with these types of things was the element of alienation, a movement away from community, where your neighbors didn’t care, need, or want to know you.

You can pick up a copy of Kill City here!

New Comments