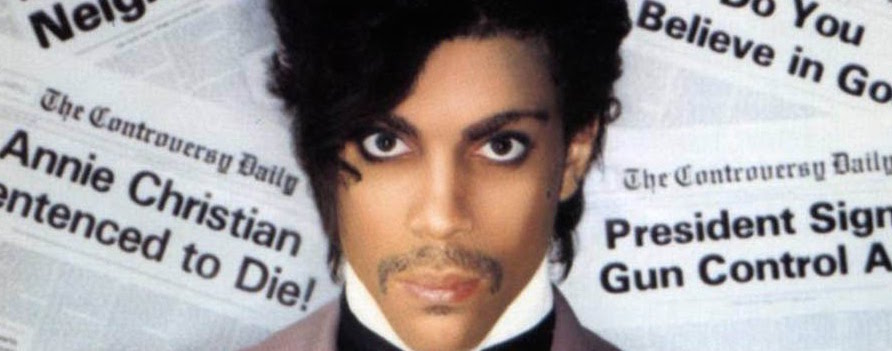

Interview by Holy Mountain

When I was around 14, all I thought about from sun up to sun down was skateboarding, punk and metal. Literally, that’s all there was room for in my head at that time – I was obsessed. One day while listening to the local college radio station, Public Enemy‘s “Don’t Believe the Hype” came on and commanded all of my attention instantly. I heard the aggression and noise of metal with the anger and in-your-face delivery of a message I loved about punk, all wrapped up neatly in a hip hop song. Public Enemy changed the course of my life, they opened my eyes to injustice, poverty and drug addiction, as well as expanding the horizons of what I was reading and listening to. Not to mention, they made incredible albums you could drop the needle on and not hear a single weak track. Public Enemy became one of the few groups to mean as much to me at 38 as they did at 14. Here is the interview I was extremely honored to conduct with group leader, Chuck D.

Twenty-five years ago, when you guys released your first record, did you see yourself in your fifties touring with the same band and still releasing records?

Chuck D: Fuck yeah! Yeah, for sure; the Rolling Stones were always our model. That’s why we call ourselves the Rolling Stones of the rap game. I don’t know if I’m Mick and Flavor’s Keith or vice versa. Maybe I’m Mick, because I’m the lead singer, and Flavor’s my support; but really, he’s the star and I’m down to play the backbone. Why not? They were always a great barometer for seeing somebody do their thing. When I decided to do it 25 years ago, I was already 27, so I said, once I started doing something I would be doing it for real.

FULL INTERVIEW AFTER THE JUMP…

So once you started it, you knew you were going for it full force?

Well yeah, I mean, I don’t make impulsive decisions – it took me a while to agree to make records, and it took me a while to say, ok this is what I’m going to do. I had my mind set on being a service person in a behind-the-scenes area, but over the last 25 years I’ve done a lot of behind-the-scenes stuff as well, so I kind of satisfied that urge by doing a lot of structural things.

Most groups can barely hold it together to get one or two records out. So with all you guys have been through how have you been able to hold it together for 25 years and countless records?

Studying other genres. Being really amazed by other genres and the history of music. Also, being able to travel the world. I think if we had not travelled outside the United States as much, our longevity definitely would not have been there. I think being able to look at other art forms as great templates is what gave us our sustaining power. That really came from the respect of collecting records – when you collect records and you understand what you’re doing, you’re able to put into good perspective where you’re at with your art form.

How was it making this record compared to the Bomb Squad production days?

This was actually an expansion, an expanded idea of the Bomb Squad in a new century. The Bomb Squad story is like five guys in a room, and we did an assembly line, piece by piece. Well, this was sort of like you’ve got 14 little Bomb Squads across the terrain, and still it has to come together with the hub of one major head producer, Gary G-Wiz, coordinating everybody’s virtual labs around the world into one solid statement. So it was an expanded Bomb Squad idea. Everybody was privy to who the Bomb Squad was, and they already had in their mind if they had to work with Public Enemy what kind of direction they would lend to the overall direction. People like Z Trip, Bumpy Douglas, Freddy Foxxx, Divided Soul, Shamello and his team. Then it was up to myself and Gary G-Wiz to be able to make a cohesive statement out of the contributions, with the way you follow the rock and roll ethic of never repeating yourself, but also you have a similarity in your technique, as opposed to the sound.

So this is just pushing the Bomb Squad idea as far forward as you can and adding more chefs in the kitchen?

Exactly. But it wasn’t like we would get this from this person, and this from this other person – it wasn’t that haphazard. This was more like: this is the plan, and you’re looking at a football field, and everybody is running their play, but it syncs. We had to have a musical texture of what the songs were about, because I don’t write songs just to meander no place at all. There had to be some substance that musically reflected the angle and direction of where we were going and what were about. I think that was reached musically for a lot of the beats.

I know that the follow up to this will be a companion album titled The Evil Empire of Everything. When and what should fans expect from this in relation to Most of My Heroes?

The records are coming out as twins kind of close to each other, one on July 13th and the other on Sept. 11th. We were kind of saluting our new digital distribution aggregation model, Spit Digital, which was making a statement that, in the past, the artistic release of records was impossible, because at the end of the day we still had factors that determined the market – like warehouses, shipping, distribution. All these areas that determined what was feasible and what was possible, now they have less of a voice as far as what will be delivered in the digital realm than they did in the physical realm. That’s why Spit Digital is the underlying story to the release of the Public Enemy album. I think Most of My Heroes was straightforward and hard-swinging with its collaborating. I think Evil Empire is a little more eclectic, and it’s doing a lot more introducing of concepts and also contributors. These albums are twins, but they are fraternal, because Evil Empire deals with the surroundings we exist in today, and how we are even kind of tackled by these situations. There is a song called “Beyond Trayvon” on the record that actually introduces Public Enemy’s sons; the name of the group is NMESUN, so the sons of Public Enemy are actually addressing the society beyond Trayvon and black life, especially young black life – always tip-toeing on the edge of danger from all aspects. There’s a song called “Everything,” and if Otis Redding was alive and could rhyme, this is what I think he would have came up with, a story-moral everyone can feel. We have things like that on the Evil album that are very clear in their meaning.

How did being a part of the label artist relationship of the past help you better deal with your career and that of the younger artists you work with?

Well, the conversation is, hey, we’re not a bank, let’s do it together from scratch. We’re not a banking system, because a banking system is basically what those corporations were. They could satisfy you in the beginning by throwing you a check and not really knowing what you were going to do. I think that I also learned that digital afforded me a window of a lot more activity instead of being stagnant.

So based on your past with the old label system and your experience now, what advice would you give a group active today on how to present themselves?

Artists don’t sell records, companies sell records, sales departments sell records – artists make records. When an artist becomes a DIY independent, it’s like you have to figure out how you sell your art and look at it as an artist selling paintings in a gallery would. You don’t see artists sell fifteen paintings in a batch, they sell one by one, and they usually have to have a conversation behind each one, and I think that’s a model independent artists should look at when they have to deal with the commerce of record sales in the market place. I think for the independent DIY artist what you know is what you say, and what you say is what you think, and that’s a model I think is really is cut and dry. What you know is what you say and what you say is what you think. Meaning, that if you don’t know what you’re in the middle of, you gotta try and figure it out. Then it’s a process of operating within what you think that you know. Either you are going to have to find somebody who knows how to do it that your going to have to pay, or make that person a partner, which is paying in another way. So there is no shortage of the need for knowledge.

I came from a punk, hardcore and metal background as a kid, but the first time I heard Public Enemy I was immediately a fan. What do you think it is that draws fans from this background to what Public Enemy does?

The straight-forwardness of our message, and the fact that we were probably introducing a whole other world that was kept away from a lot of kids, and then lastly, there was something within the mix of what we were dealing with in the music that was familiar. The aggression might be familiar, and the way the musical selection melted and molded might be familiar. There was a lot of familiarity in a lot of things we presented as Public Enemy; the fact that we operated as a group is also another familiar aspect. I just think that we always had a group concept, there wasn’t a time when someone could say “ok, you know what, I’m tired of looking at all of them.” There was something there holding people to these guys, and it might not be Chuck, and it might not be Flavor, and it might not even be Griff. I like the way DJ Lord is doing his thing, you know he took over for Terminator, and I liked the way Terminator did his thing. So the group aspect, to me, was very important, and I think one of the things that has hurt hip hop the most over the last fifteen years is the diminishing of the group and the so-called exalting of the individual. Really, black music was always away from the group, even with this recent drive to diminish the group and exalt the individual. I just think that at the end of the day, this is performance art, and when it comes down to performance art, if you don’t have a mind-boggling individual performer, it’s going to get shot in the foot because it really cannot project itself.

Public Enemy was a gateway for me finding out about so many things I may have missed. Because of Public Enemy, I was inspired to check out Malcolm X and The Black Panthers. You guys also influenced what music I listened to by checking out artists you sampled, like the Temptations and James Brown. My generation getting into Public Enemy were kids, and what you did changed the outlook for those kids who are now adults. How does it feel to have influenced a generation of young people so profoundly?

Well, I think that was an obligation that we had to do, because we felt that when we were growing up, we were advantaged by having people kind of tell us about influential people in our history, so when we became the adults, we felt we didn’t want to leave people holding the empty bag. We wanted to be able to present an opportunity, being that there is so much history in music. I mean, when they de-emphasize music history in the schools in the black community, what they do is actually subtract a large portion of black participation and involvement in history, because for the longest time, music was and is our main expression. Now today it’s different for a kid or younger adult to say “I’m gonna go check out Jimi Hendrix” on Youtube for the next hour, but that didn’t exist back then, so we had to paint pictures with words and songs.

One of the things that had a huge impact on me was Public Enemy’s anti-drug stance. What was it in your life that made this subject career-long lyrical content?

Just being able to visualize what happened in my community. Being black, and coming up in a black community, and seeing how drugs leveled my community and also my family. You stand up for something or you’ll fall for anything, and I was very clear about how I did not like the aspect of people always making excuses for drug dealers just because they made the money.

So for my last question, if you had a right to be hostile in 1998, how do you feel in 2012?

There is so much crap going down on this planet right now man. If you’re really paying attention, which is the cheapest price to pay, you’ll be madder than ever. But you have to contain that anger and make it some kind of positive, focused energy forward to make the kind of changes you want to see happen. That’s the difference between me now, and me 25 years ago.

Hefty

August 27, 2012 at 7:32 pm

Amazing interview. I’m not a fan of rap at all whatsoever, but Chuck D is a genius and an inspiration.