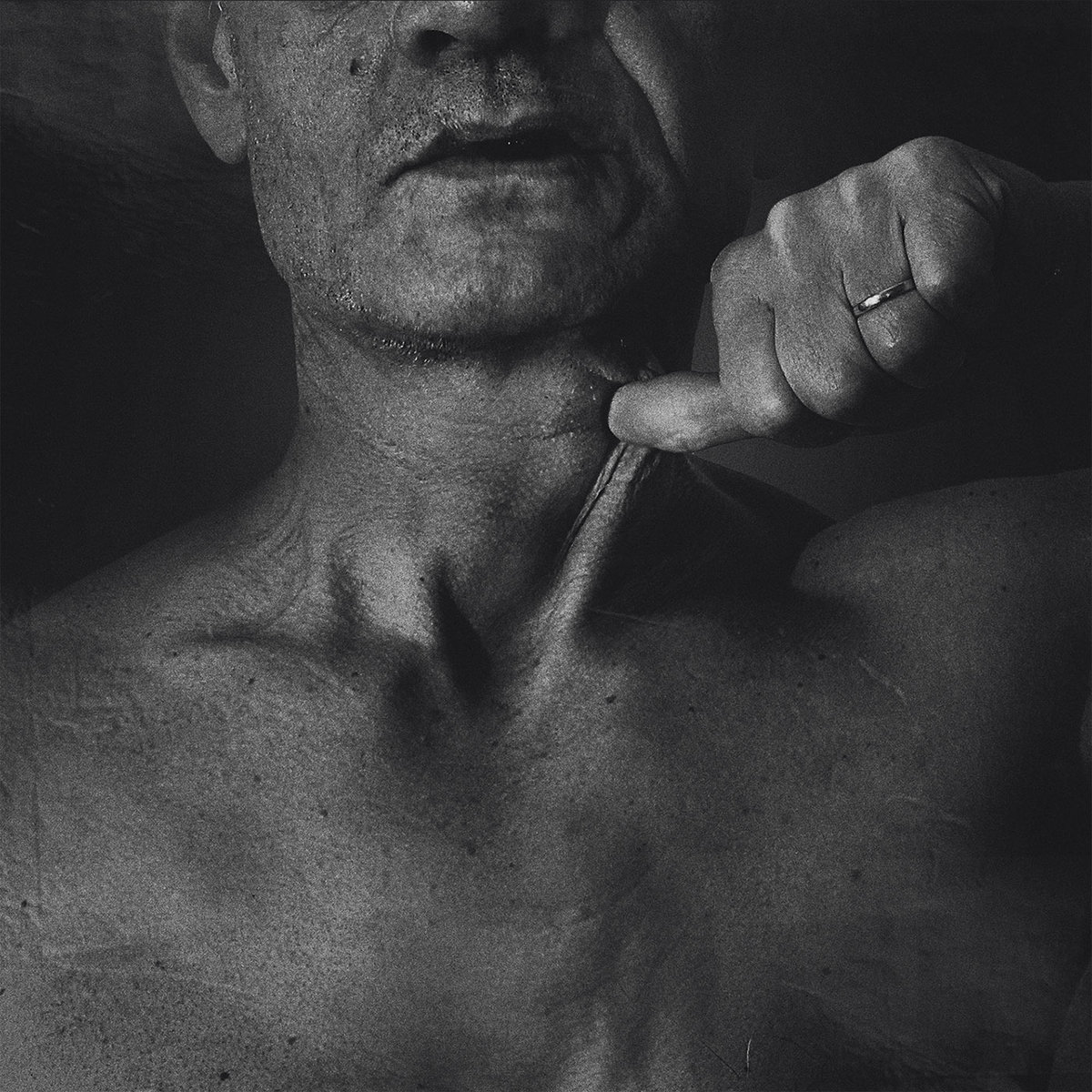

Scarification in Africa has been a practice for centuries, and probably millennia, and while it is a dying art today, it still tells a story of tradition and belonging for the wearer. The skin is pricked and cut, sometimes hundreds of times, to form stunning patterns of scar tissue, raised off the skin like braille. And it is a story of sorts, read by fellow countrymen, telling the tale of you and your ancestors, showing that you belong to a genetic line that stretches past human memory. It is practiced by many groups in West Africa, as well as in Ethiopia and elsewhere. In order to create a raised effect, clay or ash is often packed into the wound, or different substances like citrus juice are used on it to irritate the would and prolong healing. The more raised and puffy a scar is, the longer it has taken to heal and probably the more pain the wearer was in during the healing process. It is often done on children and on young women, depending on the tribe involved. I admit, when I watched the short film below documenting the photographer Jean-Michel Clajot’s travels to Benin to photograph scarification ceremonies, I found it difficult to watch small children, close to my own daughter’s age, held down and cut while they spat and writhed in pain. Despite my discomfort, I find the products of it the most striking body modifications I have ever seen, and it imparts a majesty to the person wearing the scars, a testament to their history and to the pain they endured. Below find some beautiful images of scarification, as well as a fascinating article about scarification practices in Africa.

Photo: Jean-Michel Clajot

Photo: Jean-Michel Clajot

Text via NGOInsider.com

The principal reason for scarification is tribal. It tells us about the person who bears the scars, such as which tribe they belong to and the region they come from, as long as we know how to “read” them.

Driven by inter-tribal conflicts, the tribal dimension of these scars became widespread in Benin during the eighteenth century. These indelible markings enabled warriors to distinguish members of their own tribe and so avoid killing them. As they didn’t wear uniforms or hats, the scars were the only way of telling friends from enemies. The scarifications also enabled them to sort corpses after a battle, so as to give members of their tribe the correct traditional funeral rites.

The scarifications also helped some tribes avoid the yoke of slavery, because the slave-traders viewed unscarred faces as a sign of good health, and so did not seize tribesmen with facial scars. This is why people without facial scars are considered by their fellow countrymen today to be the descendants of slaves, immigrants or refugees.

Tribal scarification is usually done before a child reaches adolescence, and children generally have the same scarifications as their father’s tribe. In north-western Benin, the Daassaba tribe’s scarifications run across each cheek, from the nostrils to under the chin. Other tribes are denoted by more or fewer scarifications across the temples, the forehead or the nose.

Some types of scarification are used to distinguish those who believe in certain gods. For example, in southern Benin, followers of Ogou, the God of Iron, have large, often bloated, cross-shaped scars on several parts of their bodies.

Others scarify their bodies and those of their descendants in honour of the gods to thank them for favours. Take, for example, the Abikou children (from Abimeaning to be born and kou meaning death, giving an overall meaning of “child destined to die”) of southern Benin and Nigeria. Women who have had several premature miscarriages can appeal to the gods to help them carry their child to term. Should their child be born without problems, the history of their dead siblings is forever cut into their face in the form of a small horizontal line in the middle of the left cheek. In cases where it is a witch-doctor’s skill, rather than the intervention of a god, that has helped the woman to give birth, the child is scarified with the witch-doctor’s tribal marks, and is called a Yoombo (“purchased child”).

Many inhabitants of the town of Ouidah in southern Benin still practise the so-called “two-times-five” scarification, which consists of small pairs of vertical scars in the centre of each cheek, another between the eyes and two more on the temples. Legend recounts that this scarification was first performed in 1717 by King Kpasse when threatened by a rebellion led by Ghézo and his warriors. Heavily outnumbered, Kpasse fled into a python-infested forest. The snakes did not attack the king: instead they helped him to counter-attack and force his enemies to surrender. Henceforth, all Kpasse’s descendents have born the same scarifications and have held pythons to be sacred, honouring them at numerous festivals, and severely punishing anyone who kills one.

Finally, some tribes in north-western Benin and north-eastern Togo are so proud of their scarifications that they copy them onto the walls of their Tata Somba(house). Just like the road signs we encounter when we arrive at a settlement, these interior and exterior decorations show us who the inhabitants are.

“An act of bravery” says Martin Sakoura, a pastor from Natitingou.

Facial scarifications can be used to tell us about the family history of an individual, but the “reading” does not stop there: many men and women have scarifications on their backs, arms, bellies and shoulders which give us more personal information about them. Yon wan (from Yonka meaning fish and wanmeaning bone) scarifications are sometimes found on their arms or bellies. They are easy to spot and bear witness to the bravery of those who bear them: the more scarifications, the braver the individual. The first Yon wan scarifications are done when children are 9 or 10 years old, and the last when they are between 20 and 25 years old, when the boys are circumcised, after which the Yon wan cease.

In the Atacora district of north-western Benin, young women ask to be scarified with puuwari (from waama puuku meaning belly and warii meaning writing)when they are in love, so that all their relatives know that they intend to marry. Puuwari scarifications cover the chest and the belly with rows of small vertical and horizontal scars, and take a long time to do. Once completed, they tell the girl’s mother that she is ready for marriage.

In the Bétamaribè tribe, young brides are subjected to a further ritual: before they become pregnant for the first time, they scarify their buttocks with vertical scars to ensure a lack of birth complications.

“People don’t want to scarify their children any more, so that they don’t stand out from the crowd” says Florent N’Tcha N’Dah from Natitingou.

Scarification is becoming increasingly rare in Africa. In Benin, it has almost disappeared in urban areas, due to the reaction of the French colonists who viewed it as barbarous, forbade it and even punished those who practised it.

The hygienic problems associated with scarification are obvious. Many campaigns are underway to inform villagers about the risks of infection, in particular with HIV and tetanus. The scarifiers, who view their practice as sacred, obstinately refuse to start using disposable blades or to sterilise their knives.

The rise of other religions is also leading to the progressive disappearance of scarification. Seen as part of animist beliefs or folklore, they were forbidden and condemned by Christianity. Islam also banned them, as the Koran extols the integrity of the human body.

Finally, new Western styles of dress prevent scarifications from being seen clearly and thus remove their value.

Photo: GEORGE STEINMETZ

The combined effect of these three factors is gradually driving out this ancient ritual, to the rage of the elders, who are powerless to stop it. For them, scarification is something to be proud of: it demonstrates a person’s pride in belonging to a tribe or a family. They like the idea that this membership can be recognised both locally and abroad. Scarified expats can be recognised in a few moments by members of their tribes, anywhere in the world. Individuals continue to have children, because refusing to do so would contribute to the demise of their families. By not bearing scarifications they create the same effect of renouncing their roots and allowing themselves to be treated just like everyone else.

New Comments