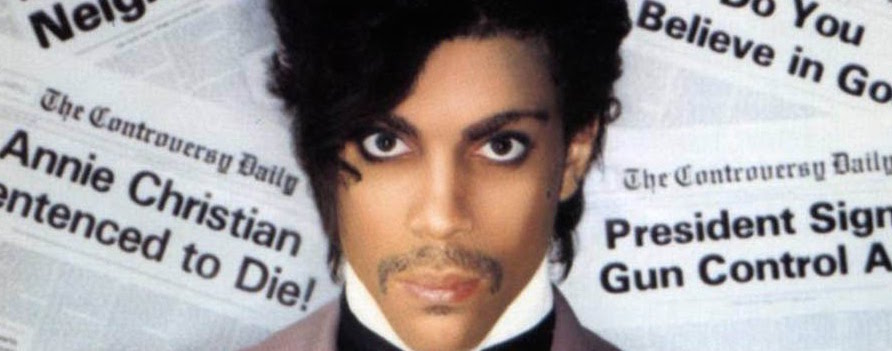

Story Source Village Voice By Brad Cohan

Joe Carducci not only played a monumental role in helping run and co-own SST Records in its glorious 1980’s heyday when Black Flag, Minutemen, Hüsker Dü and Meat Puppets were the reigning kings of the Amerindie underground, but he also famously penned the lyrics for the Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime classic “Jesus and Tequila,” and later on, wrote tunes for Mike Watt.

But above his legendary SST Records pedigree is Carducci, music scribe figurehead and film and political pundit. He penned the definitive manifesto sprawl of the history of rock music called Rock and the Pop Narcotic (originally released by Henry Rollins’ 2.13.61 imprint in 1991) and recently authored Enter Naomi: SST, L.A. and All That, an inspirational yet gut wrenching account of his SST friend and punk rock photographer Naomi Petersen, who tragically passed away from liver failure in obscurity in the mid-90’s.

Since 1995, Carducci has lived in Wyoming, banging out screenplays, short stories, keeping an extensive blog that hardcore godhead Keith Morris love and running Redoubt Press, his own DIY-operated publishing company. He just self-released Life Against Dementia: Essays, Reviews, Interviews 1975-2011, the comprehensive Carducci collection righteously on par with that of Richard Meltzer’s A Whore Just Like the Rest and Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung by Lester Bangs.

Sound of the City sat down with Carducci to talk about his new book, the SST days and the false reportage that he was averse to signing Sonic Youth to SST. He reads tonight from his latest book Life Against Dementia: Essays, Reviews, Interviews 1975-2011 (Redoubt Press) at BookThugNation at 7:30pm in Williamsburg (100 N. 3rd Street; between Berry St. and Wythe Ave.)

Did keeping your blog The New Vulgate serve as the inspiration to compile the content for your new book, Life Against Dementia?

I was thinking about the collection before we started the blog. But the Vulgate made me get productive and wound up providing about half of Life Against Dementia. It also allowed me to chop down the interview sections to just a short piece of the older interviews that haven’t been posted online.

For someone who seems to be a proponent of old media, you are certainly engaged in social and new media. You are on Facebook and running The New Vulgate blog is use of a new media contraption.Is engaging in new and social media done reluctantly on your part? Was putting out Life against Dementia your way of keeping the printed page alive?

I like doing the NV and fishing around Googling for images is sometimes the most fun part of it. But I really regret it can’t be a publication, even as an annual. I only stopped thinking about that when Tower (Records) went under. After that it seemed impossible to believe it could be in print. My next book, Stone Male, is the end of these run of titles. After that I hope to be getting screenplays produced and have reason to write new ones. That’s really what my writing is geared for, and probably why my nonfiction essays and critiques don’t read like most others in that game.

Looking back at Rock and the Pop Narcotic, is there anything in it you got wrong? Do you have a desire to write a “sequel” for it?

I did want to revise it slightly before reprinting it, but I had the 2.13.61 film ready to go and there weren’t material changes, just typos and a few informational mistakes, where this or that band was from, etc. I do feel I understand several things much better than I did. In my essay, “David Lightbourne & Outlaw Folk in ’70s Oregon,” the relationship of parts of the folk music scene and acoustic country and blues music going back to the turn of the century to rock and roll is featured, whereas there’s almost nothing of that in R&TPN as I didn’t know enough to care back then. A lot of what might have been improved or added to R&TPN is in LvD; in the title essay I write about the way the repression of punk in the ’70s by radio, even major label punk, proved to be a kind of oxygen deprivation which has retarded the music culture in ways that can’t be repaired. I start the collection by talking about a certain oxygen deprivation leading to retardation, culturally. It’s what happened when the punk bands on the major labels were rejected by Lee Abrams’ radio consultancy. His judgment, backed up with Jann Wenner’s at Rolling Stone, meant that the majors stopped trying. Thereafter we got the rock culture Lee Abrams and Jann Wenner determined. That we hear the Ramones at baseball games now can’t undo that 15 or 20 years of oxygen deprivation.

Where does the title of the book come from?

The title refers to Norman O. Brown’s book, Life Against Death, which with Paul Goodman’s Growing Up Absurd and a few others, was one of the books that started the ’60s. Those were the intellectual sociological paperbacks that were littering the bookstores. I think my title works, and that was its title when the earlier version ran in the first issue of Arthur Magazine. In a way, it’s a more accessible book because you can pick the film stuff to read, or the music stuff, or my take on the CIA in Tibet.

On to the SST Records days. Do you keep in touch with any of the SST folks?

Henry (Rollins), the most consistently. He put the Rock book out at one point. It’s not every year but if I go out to L.A. I’ll usually see if he’s in town or maybe (Raymond) Pettibon. With (Chuck) Dukowski, it’s mostly email. When I first saw Chuck’s Sextet, they didn’t have a guitar; they had a saxophone. I had just seen Thurston Moore and a percussionist at The Stone and I thought “Man, Chuck’s band as it was then would have fit into an artier thing in New York.” I’m glad Chuck is happy. He looked like he was under a lot of strain back in ’83 [laughing]. When the strain was only the LAPD, he was happy. He loved that fight. But when it was him versus Greg, that was really, within the band, rough on Chuck.

When you joined SST in ’81, did you know what you were getting yourself into?

Not entirely [laughing] but I wanted to get back to L.A. I knew it had been a mistake because Rough Trade did not want to live in L.A. or neither did my partner in Systematic. I remember hearing the (SST) stuff on the commercial FM stations. They’d have an import program or Rodney would be on on the weekends on KROQ. So I knew that there were business chances. I didn’t know until we got to the Bay area and we reissued the first Dead Kennedys singles and the Pink Section 45. But there was no pressing plants in the Bay area so we were pressing in Cincinnati. There’s no way to time anything because you’re last on their list of priorities. That was a big mistake but what little I knew about Black Flag I liked. I had written a very bad rock and roll band script two years earlier and that’s what I had named my band (Black Flag). So I was already a torublemakin’ anarchist before the music involvement.

What were you into when you went to SST in ’81?

I was really into Flipper when I was in Berkeley and in Portland The Wipers were playing. Up there I saw all the New York bands played. Television was on their second tour, The Ramones were probably on their third tour. The big ones would play The Paramount–The Ramones and Patti Smith played the Paramount. Television played a little bar.

Did you agree with Richard Meltzer that L.A. punk was superior to New York punk?

I’m glad he says that because he’s right that that [L.A.] was the place to be because the depth of the scene and everyone thinks its superficial, but it never ends. I hoped the Naomi book, where I just keep redrawing the circle of what was going on there, because Brendan Mullen was very protective of the scene he was a part of. His relationship with Greg was interesting because they went up and down over the years and he never thought Black Flag was functional enough to play the Masque when they complained they couldn’t give a hooky but it was mostly Keith, complaining.

I didn’t know he (Brendan) was gonna be ill and die so quickly; I figured I’d be on a panel with him someday and we’d argue this out.

How did it ultimately work out that you wound up at SST?

I met Black Flag a couple times in the Bay area and in Chicago actually when I was visiting family. I knew they were doing it, in a way that the Dead Kennedys weren’t. The Dead Kennedys were split. I think Jello wanted to do it but he didn’t know he could do it so he wouldn’t demand it and Ray had been the guy we had bought singles from; we put on their show in Portland. This is where we met them, talked to them, came down and they said “Come down” because they weren’t happy with the options in the Bay area at the time. So we (Systematic) ran a second thousand of the first single. It wasn’t a raging hit but they eventually sold the first thousand. It started growing and we did the first run of “Holiday in Cambodia” and that became a big deal. They took that away from us because they thought we couldn’t handle it because again, we had no pressing plant. You can’t run across town for an emergency. All we could do it call somebody in Nashville and try to talk to them about a band called Dead Kennedys [laughing]. Right after I got down to SST, Dead Kennedys played the Whiskey or something and Jello stayed over at SST and he said that they were looking for a guy, “a Carducci,” to run their label, because when I had left them for Black Flag, they must have thought “Well, we coulda done something.”

Why did you leave SST in 1986?

Well, Greg was glad I was goin’ because I sort of broke the logjam. The practical matter was Mugger and I had more and more planning to do with more bands, even in the early years when it was really just five bands maybe six bands. So in the end, we had to say “No” about budgetary planning on certain projects or whatever. If you look back and see how many records Black Flag did, we didn’t really say no to too many things and I didn’t want to say no to Greg–it was his label, always. In retrospect, and I told this to Chuck, we never should have split the band from the label. We were all in one office and it was kind of difficult. Hence, we had to store our records and we had more records to store. So, we were gonna keep moving into new places but we had this place for 150 bucks that we didn’t want to lose and they wanted a practice pad, as well. It just came to be that once the band was out of the label building, the typical paranoia down there made it impossible to then reconnect when you had reason to at a gig or to talk about matters. Phone was enough [laughing]. Those guys favorite sport was trying to figure out what song lyrics were about who and the grand accusatory “you,” which is, in the old days, that was the style. So the question is “Who is ‘you?'” The Minutemen were into that theme and Saccharine (Trust) and Descendents and Black Flag.

Did you consider yourself punk or hardcore?

No. I never shaved my face my whole life. If you look at the old photos, there’s always some bearded guys in the 70’s in the punk rock bars. But by ’80 in the hardcore years, there’s nobody with a beard in the place. Then there were photos taken right before Ian Curtis killed himself and those guys had whisky, little beards. Then you found some of the goth people playing around with Frank Sinatra records and the legend of Joy Division. Beards and Frank Sinatra. But they were not at our gigs. I was never beat up because I was recognized as being “Oh yeah, that’s Henry’s hippie or Greg’s hippie.”

Did you keep in touch with Ginn after you left SST?

I tried to stay in touch through the mail, if I had an idea or just a comment or send him a tape. I was getting promos for about a year (after I left SST) and they were doing a lot of stuff. I don’t know where the cutoff point was–it was probably when Ray Farrell got fired. As it went, I was researching my Rock book, which didn’t come out ’til ’90, so for another four years I was running around record stores buying. Everyone was dumping their vinyl for CD’s so it made it real easy and cheap to buy ones of every band you ever picked over and ignored for research.

Writing the Rock book must have been an exhaustive process. What went into it?

Rock and the Pop Narcotic started in L.A. after I left SST. I began reading back issues of Slash, making notes and doing stuff. I moved to Chicago and spent ten months rehabbing a building, but that downtime helped me figure out the structure of the book. In the end, its two books really, because the history back end–if I hadn’t done that, I don’t think people would have known what I meant by the first half of the book. You really have to run the history through the theory then people go “Oh, this is what he meant.”

It’s been documented that you were against SST signing Sonic Youth. Is there any truth to that?

Alec Foege, who wrote the first book (Confusion Is Next: The Sonic Youth Story), has something in there that’s just wrong. He never talked to me about any of it. But people assumed I was the A & R guy and I said “No.” That’s absurd.

People think we had an A & R department when it was really just mostly Greg and Chuck and me and then Henry had an influence and Mugger and Spot brought bands in–if we could do it and we would talk about it. I hadn’t seen Sonic Youth. They had sent their records to Raymond and I had read Kim had written about Raymond and the records his art was associated in ArtForum. That was from left field, as far as I can tell; I didn’t know she was in Sonic Youth. Thurston had sent–I don’t know, maybe it was Bad Moon Rising on a cassette, with his ‘fanzine. I told David Browne (author of Goodbye 20th Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth) that I took the ‘fanzines and threw the cassette in the demo box and the demo box went over to Global. So I never listened to the Sonic Youth album there. But I was collecting ‘fanzines and I still have those (desperate) Killer ‘fanzines that Thurston was doing. Ray Farrell came down so he was really into Sonic Youth, Naomi was really into Sonic Youth, Henry was really into Sonic Youth. When I heard their records at Pettibon’s I said “This is what they sound like?” and he said “Well, they’re doing something with the culture.” But in the end, they got a good drummer–two good drummers–and I’ve liked what they’ve done. I think with Washing Machine and the later period (records), they don’t sound contrived to me–I think they got to be better songwriters. The new Lee (Ranaldo) album–I liked that.

Was it Bad Moon Rising you listened to back in the day?

No, it wasn’t. I liked Bad Moon Rising when I finally heard it. I got a copy from Joe Pope at Systematic. I liked Bob Bert as a drummer. I never saw him play with Sonic Youth live but I didn’t like Richard Edson as a drummer. I’ve liked Edson since then–I’ve met him and he’s a great character, a great actor. The other thing was Greg had seen them play and what struck Greg was they had these little amps–I don’t know how big they were. Lee and Thurston had these little amps and Greg thought they were just hamming it up and making fun of rock music.

Finally, will you shop Stone Male to major publishers instead of doing it yourself?

They won’t take it as is–I know they won’t. So, the hell with it. I got one more self-published book in me. I might as well do it myself.

robb

October 16, 2012 at 7:14 am

great read!